Raja Lubinetzki is an East German-born poet and artist. Diane Izabiliza sees a lot of power in her work at a time of reawakened nationalism.

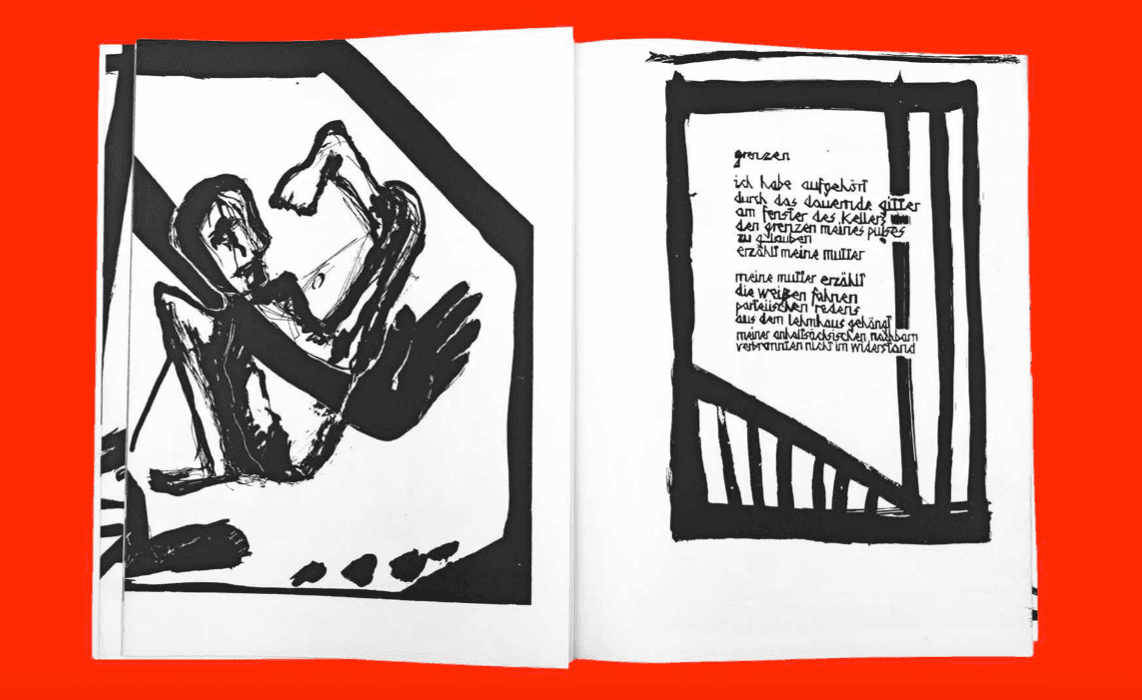

Graphics: Petra Schramm (Berlin, 1989). Photo: Benjamin Renter

At a time when right-wing populism, nationalism, and racism are once again socially acceptable under the guise of a need for security, [Raja Lubinetzki] gives me hope.

When I read the name Raja Lubinetzki, it didn’t seem familiar right away. But then I remembered having read her story in the book Farbe bekennen: Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte (Engl.: Showing our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out, Amherst, 1991). Published in 1986, the original book is now one of the milestones in Black German history. It is a compilation of historically reviewed Black biographies in Germany, which the editors supplemented with (then) contemporary interviews. One of the women interviewed was Raja Lubinetzki. At the time of the interview, she was 23 years old and spoke about her life as a young Black woman from East Germany. She talked about her experiences and how she dealt with racism and sexism, also giving insights into her development as an artist.

Lubinetzki was part of the artists scene in Prenzlauer Berg, a district that was then known as the “other GDR”: a non-conformist neighborhood by GDR standards, characterized by the artists and workers living there. In 1987, Lubinetzki left the GDR for West Berlin, where she still lives and works today. Her texts and drawings have appeared in numerous magazines, and she has published several volumes of poetry. Today she is best known as a poet and painter.

What is remarkable is that Raja Lubinetzki’s works were mainly printed by small East German publishers–even after she had left the GDR. Some of these publishers no longer exist, others are slowly dissolving their stocks, and it is not surprising that a Black artist from East Germany is affected by this marginalization. Gaining access to Lubinetzki’s works is made more difficult by the entanglement of different systems of oppression. In a cultural sector that is white and male, it cannot be taken for granted that a Black East German woman’s work is considered relevant. Black women artists in particular are often accused of being too specific–too Black, too female, or not enough of both. Their works are often seen as exclusive if they do not address Blackness as a deviation or focus on the Black experience, thus becoming acting and multilayered subjects.

Lubinetzki’s poems and drawings are important contemporary documents, although she had to overcome some obstacles in order to make her voice heard. At the age of 23, she described her professional career as full of stumbling blocks, as she lost her job several times and had to find new work. She was able to complete her training as a typesetter, but then worked as a gardener and household assistant.

In this, she is not alone: it is a story that can be found in many of the biographies of racialized people and is the result of institutional racism. But like many others, Lubinetzki resisted in order to pursue her own path.

Looking back at the fall of the Berlin Wall, whose thirtieth anniversary is being celebrated this year, I wonder what it must have been like for racialized people to take the floor–to inscribe themselves into a narrative they were not meant to be a part of it, at a time when the white (West) German narrative was even more dominant than we know it today I wonder what it was like to write then in spite or precisely because of this.

Innen hör ich Schall. Poems: Raja Lubinetzki;

Graphics: Petra Schramm (Berlin, 1989). Photo: Benjamin Renter

Writing can be a very intimate, demanding, and liberating act. Through writing and play, we sort and analyze our thoughts. In the best case this is truth-speaking, which brings about change and further development. In a society that hinders marginalized and racialized people from speaking out and expressing themselves, this act is a survival strategy that also serves to share experiences and pass them on to the next generation. For me, it is always a challenge to face my self-doubts, to find my voice and not to be distracted by isms. Hence my great appreciation for those Black people who did this at a time when it was almost impertinent for them to write or compose poetry in German, to act independently, appearing vulnerable and strong at the same time–in a society that did not want to see them.

In one interview, Raja Lubinetzki talks about not having had any other choice but to write. She chose her topics herself and also rejected any request to write more about her Blackness. Nevertheless, Blackness is a topic that can be found in her poems, although she seems to have decided, independently of the expectations of others, if, how, and when she writes about it.

Many of Lubinetzki’s poems feel heavy and leave you with a lump in your throat, while some have the effect of a single big middle finger. But the artist wraps her sharp words in a sonorous cloth. People like Raja Lubinetzki have contributed to countering and changing ideas of hegemonic German historiography. At a time when right-wing populism, nationalism, and racism are once again socially acceptable under the guise of a need for security, she gives me hope. Even today, almost thirty years after reunification, the mainstream is asking who is German, who is allowed to belong, and who can be denied basic human rights depending on where they were born. The slogans of the past sound different today, but they can still be heard both on the margins and at the center of society. There are parallels with the past and still a great deal that is new.

The fact that today I can engage with the writings of Raja Lubinetzki and other Black people and people of color makes it clear that they have paved the way. These paths need to be consolidated by repeatedly being invoked and retrieved so that they remain visible in a changing world.

The graphic illustrations come from the artist’s book Innen hör ich Schall by Petra Schramm. Raja Lubinetzki wrote the poems for the book. Berlin, 1989. Photos of the illustrations: Benjamin Renter.

By Diane Izabiliza.

More Editorial