Opacity is a Different Kind of Clarity

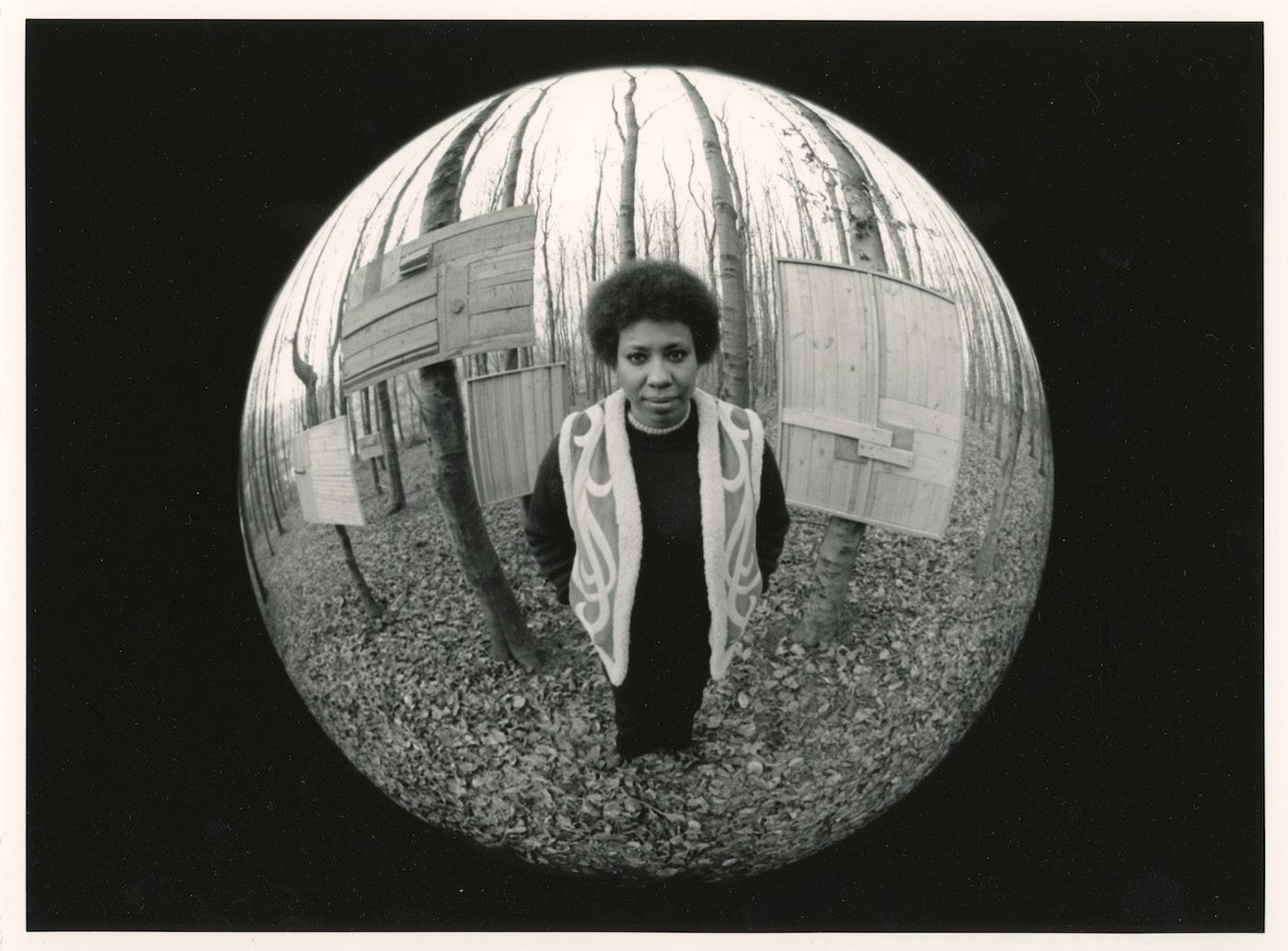

Since the announcement in late 2016 of Gabi Ngcobo as the curator of the 10th Berlin Biennale, anticipation has been running high – and the expectations too. Ahead of the opening, C&’s Julia Grosse sat down with with Ngcobo and Yvette Mutumba, one of the biennale’s co-curators and C&’s co-founder, to talk about the meaning of refusal, how they’ve dealt with various kinds of expectations, and the importance of saying things with a different kind of clarity.

Contemporary And (C&): The biennale’s title, We don’t need another hero, as well as the title for the public program, I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not, underline a position of negation or refusal, in a good way. Where do these negations or refusals come from?

Gabi Ngcobo: I guess they come from different places. I think one is an expectation of what the biennale will focus on based on our subject positions. The negations can be read as a way of distancing ourselves or escaping a certain kind of expectation so we can work with the freedoms that other curators don’t even have to claim. And it became necessary to have these kinds of negations, especially with the public program title.

C&: Why the public program title in particular?

GN: Well, we decided to start the public program a year before the biennale would open. So it became an important tool to create a space, to have this conversation freely, and not to wait until the artist list was released. The public program helped us set the tone for the Berlin Biennale, but also to figure out how to work with the organization of the biennale itself.

Yvette Mutumba: It also helped us a lot, while we were on the go, to think about what refusal even means. We had a lot of conversations figuring out if it’s against something, or whether it’s about being elusive. Is it something positive or negative or even violent? In that sense it was quite useful that people had certain expectations – or still have – because it forced us to really think through what our language is, or what language we want to use that stands against those expectations.

Portia Zvavahera, Hapana Chitsva (All Is Ancient), 2018. Oil-based printing ink and oilstick on canvas, triptych, part I, 204 x 126 cm. Courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

C&: The title We don’t need another hero seems to focus on collective power.

GN: Yes, I think that’s important. You know, when people like us – also women in general – go into these power positions, often they’re not interested in changing the rules of the game. They kind of play that game as they find it – as it’s defined by, let’s say, hierarchies defined by white male power. Over centuries. One has to be careful about how one refuses that position, because of course we are not refusing our subjectivities, and the fact that when we start thinking about the exhibition itself we think from

a certain perspective. We also get asked questions that would never be asked to other people. There are a lot of other people who think that we start from the same position, especially white women. They make remarks about a shared subject, focus, or theme, but for us this is not a matter of interest or focus – we can only begin from here, it’s our reality, this is us – it’s not our subject.

C&: In terms of representation, when the news came out that you would be heading the Berlin Biennale, what was the feedback from the Black art world – did it also bring forth certain expectations?

GN: Well yes, those expectations are the other side of the same coin, actually. Our negations were influenced by different sides, of course. So we try to find the language …

YM: … to also confront those very specific expectations.

GN: It’s Antonia Majaca who has written and delivered a couple of lectures titled Against Curating as Endorsement, and I think that’s a really important position. For us this project is also not about gathering together people who agree with each other, or with us.

C& And you’re not representative of anyone. YM Exactly. Because that cannot be our job either, to cater to expectations.

GN: And a lot of expectations directed at us were assumed that we would of course work with certain culturally specific institutions in Berlin or address certain unresolved questions that have been at the center of the cultural landscape, such as the Humboldt Forum …

YM: And it was very clear that we would not be interested in addressing those venues. At the same time, with Akademie der Künste for example, how we relate to the works shown there is still very political and historical.

C&: How did you negotiate the selection of lesser-known artists and big names, as well as non-living artists?

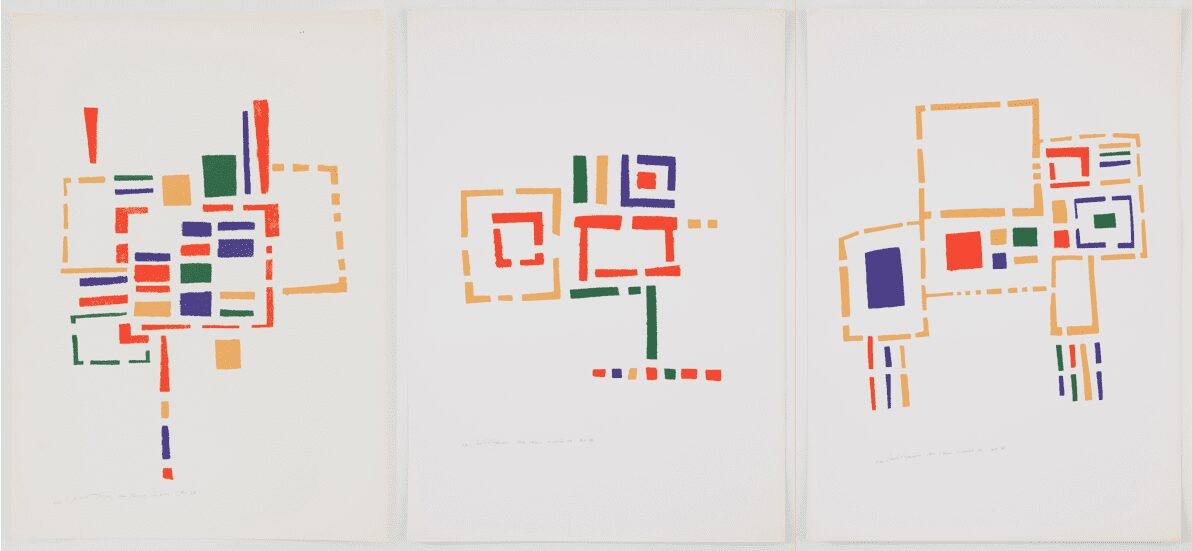

GN: Well, we didn’t sit down and say, “We need dead artists.” It was a series of conversations and chance encounters, which were quite great. Nomaduma Masilela, from our curatorial team, encountered the work of Mildred Thompson when she was working at MoMA and started to research her work. Thompson in fact created a lot of work in Germany when she was self-exiled from the USA. We thought it would be an important position to bring through. We wanted to have strong female perspectives in the exhibition, and so there are those that are not alive anymore but what they did was very important – also their deaths maybe. Women like Gabi Nkosi and Belkis Ayón and Ana Mendieta. The fact that we have more female artists is because these are positions that we are interested in and that are most visible to us. We see them.

YM: We see them and then we connect with them, and that’s exciting. With Mildred it was great to find all these things out,

like this interesting German connection, also in terms of a broader context and in relation with Audre Lorde and other people who are important for us. I think that’s the same with the big names, and not-so- known names. Some say every big biennial “needs” two or more people who are being “discovered.” It was really clear that we didn’t want that. So if there’s an unknown name, it’s not because we want to unearth this name from Africa or wherever.

(left) Mildred Thompson, Untitled (No. VIII), 1973. Silkscreen print on paper, 61.3 x 42.9 cm. (middle) Mildred Thompson, Untitled (No. IV), 1973. Silkscreen print on paper, 61.3 x 43 cm. (right) Mildred Thompson, Untitled (No. III), 1973. Silkscreen print on paper, 61.1 x 42.9 cm. All Courtesy The Mildred Thompson Estate and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

C&: I like your idea, Gabi, that as an artist you add a touch of deviancy to your curatorial roles. Because you have also worked as an artist.

GN: In this project and in my general practice, I think it’s an interesting part of my life to retain. That doesn’t mean that I exist in a studio, but I think keeping this identity allows for this deviancy. I am not governed by the rules that I didn’t make for myself. And I don’t think that artists are more special than other people doing important work in the world.

C&: Let’s talk about Berlin as a city, with its deep, complex historical layers – how did that inform your thoughts about the Berlin Biennale?

GN: I don’t think this exhibition would be possible anywhere else. We didn’t want the weight of history to overwhelm us.

Of course, it’s there. But we point to these things in very poetic ways. And we hope that people in Germany, in Berlin, will find things that resonate …

YM: Also, there are [history-related] activities and interventions already happening in Berlin, so we did not want to reinvent the wheel. I think it’s a little bit like what I said before, with regard to the venues, where there are historical references but they’re not an obvious framework for the exhibition.

GN: Avoiding the about-ness.

YM: Exactly. And we have certain artistic positions that go very specifically into these histories. The installation by Zuleikha Chaudhari, for example, deals with an aspect of the city that is not well known – it explores the complicated trajectory of Subhas Chandra Bose (1897–1945), a charismatic leader of India’s struggle for independence. Not only did the Nazi government help fund the Free India Center in Berlin, where he served as an ambassador of sorts, but it embedded his Free India Radio programs in its own propaganda broadcasts to India.

<p>

Mildred Thompson, [Woodwork], 1969. Wood, nails, green paint, 90 x 103 x 6.3 cm. Private collection. Courtesy The Mildred Thompson Estate and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

GN: Also, in terms of the spaces that we chose, the environment of Akademie der Künste, the fact that it’s surrounded

by a garden, and that people can create some breaks within the space itself is also important. It’s the same with ZK/U – Center for Art and Urbanistics – it has a public park, greenery, where people can also rest. With regard to the Akademie there is also the fact that it holds a lot of history within its vast archives, so vast that no one who’s alive knows everything that’s in there. And I think for us it was important to enter those archives to be able to look at certain things.</p>

YM: So we visited the archives, digging out material, like posters and artworks which reflected the connections between the former East German Akademie and socialist countries like Cuba.

<p>

Mildred Thompson, [Woodwork], 1969. Wood, nails, brown paint, 90 x 103 x 6.3 cm. Private collection. Courtesy The Mildred Thompson Estate and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

C&: Are you going to show them?</p>

YM: It was more an awareness of what’s there rather than literally putting them into the exhibition. To see what kinds of histories the Akademie contains. Also to understand what stands for artistic excellency in the context of the Akademie: for centuries it was Western, white European, male positions. Of course bringing in the artists that we chose is also a statement of saying what artistic excellency can also be, as the Akademie is still about membership, still an exclusive club.

C&: Speaking of awareness – the graphic colors and the pattern of the Berlin Biennale, what do they refer to?

GN: The dazzle camouflage is also a kind of a negation – the idea is taken from war- historical narrative. In World War 1, ships were painted in different color patterns so that they were not easy targets. So it meant that whoever was trying to attack the ship was not really sure of the direction it was taking. It’s an interesting history, because it was to obscure the direction, the size, and the intention of the ship, but when you read more about it, it didn’t help that much – the ships that were painted in dazzle were attacked. Perhaps even more than those that didn’t have it.

C&: Because they tried to become invisible?

GN: Yes. Not invisible per se, but to be differently visible. Because of course they could be seen. For us the search for language is the search for a language to be differently clear. To speak about the same things have been spoken or written about for hundreds of years, and to see if we can say it with a different kind of clarity. It also allows for this position to be opaque, in the knowledge that opacity is a different kind of clarity.

Intreview by Julia Grosse.

This interview was initially published in our new C& Print Issue #9. You can read the full magazinhere.

En Conversation

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

« Considérer le processus avec soin et intentionnalité » : Favour Ritaro perpétue des legs essentiels en matière de commissariat d’exposition

En Conversation

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones