In our latest series – Female Pioneers – C& looks at female artists from Africa who have made great contributions to art on the continent. Here, Liese Van der Watt explores the trajectory of acclaimed Kenyan ceramicist Magdalena Odundo and her current exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield in West Yorkshire.

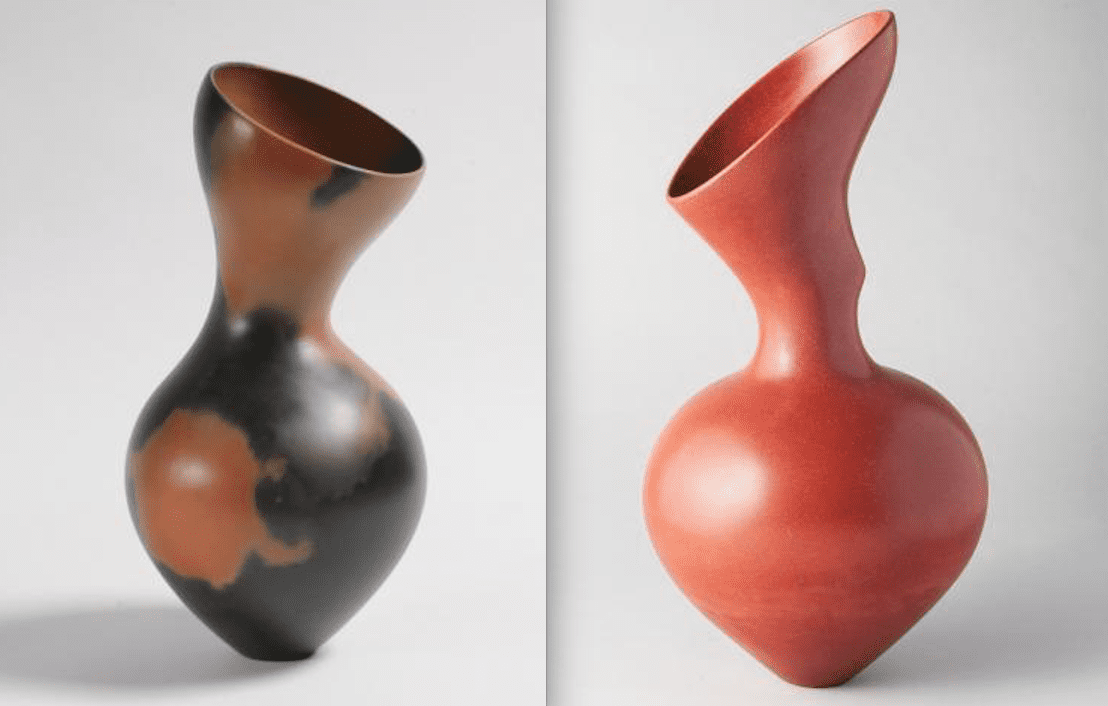

Magdalene Odundo, (left) Asymmetrical Betu II, 2010. Red clay, carbonized and multi-fired, 53 x 27 cm, signed under base. (Right) Assymetrical Series, 2017. Terracotta vessel, 24.5 x 12.5 inches {62.23 x 31.35 cm}. Both images courtesy of Anthony Slayter-Ralph.

In many traditional African societies, clay pots and vessels are made by women. Shaped by hand, decorated or not, they fulfill mostly domestic needs and are used to collect and keep water or beer, to cook in and to eat from. Because these items are functional household items they fall in that murky category of “craft,” where objects are historically attributed to anonymous makers, often the domain of women.

It is therefore easy, if stereotypical, to assume that a female ceramicist of African descent is merely continuing a tradition that she was born into, one that is somehow part of her very being. But for acclaimed Kenyan ceramicist Magdalene Odundo it was a long journey. After finding her preferred artistic medium – clay – she’s been on a long and circuitous passage starting in England, taking her back to Africa, and culminating in the ceramic art works that she has become so famous for: beautifully simple and perfectly accomplished hand-built anthropomorphic vessels, burnished in black and red tones. These pieces are hybrid creations – they gesture to Africa but also to Europe and Asia, they speak of Greek and Roman influences but also of indigenous African traditions.

Magdalene Odundo, Symmetrical Series III, 2009. Red clay, multi fired, 16.9 inches/43 cm high. Signed and dated underneath. Courtesy of Anthony Slayter-Ralph.

Odundo was born in 1950 in colonial Kenya and educated in Catholic schools where girls were taught drawing and needlework, but not art as such. After school she studied commercial arts in Nairobi and then moved to England in 1971 where she was first introduced to clay in 1973 at the University of Creative Arts, Farnham. She describes her early successes at centering clay on the wheel as a transformative experience, the beginning of what became an ever-closer relationship with the medium that is partly based on learning, labor, and studies, but is also intuitive and responsive.

While studying in Farnham, Odundo met Michael Cardew who had been appointed “Pottery Officer” by the British government to teach and modernize local pottery traditions in Africa, first in Ghana during the Second World War, and from 1950 in Nigeria. Cardew established the Abuja Pottery Training Centre and encouraged Odundo to visit. She spent three months in Abuja, learning wheel, coil building and kiln firing from local craftsmen and particularly -women, such as the gifted Gwari potter Ladi Kwali whose picture is on the 20 Naira bill.

When Odundo returned to England, she decided to do a Masters degree at the Royal Academy of Art focusing on hand-building, honing her coiled vessels to become the minimalist and smooth art works that they are today. These pots are not glazed but derive their color and shine from respectively thin layers of slip and hand-burnishing the items before and after firing at extreme temperatures, sometimes multiple times. Odundo was drawing on techniques she had learnt in Africa, combining them with the teaching and influences she was encountering in Britain. Her inclusion in Susan Vogel’s pioneering New York exhibition Africa Explores in 1991 – one of her vessels is on the catalogue’s cover – not only introduced Odundo’s work to the international art world and market, but also positioned her as an African artist, albeit one that was working far outside the clichéd expectations of what « African art » should look like.

Magdalene Odundo,Untitled, 1989. Burnished and carbonized terra-cotta, 44 x 38 cm, Signed under base. Courtesy of Anthony Slayter-Ralph.

Odundo speaks of clay vessels as having an inside and an outside, a skin and a body, and therefore being able to express her inner thoughts. Her vessels capture stances, gesture, and movements; in interviews, Odundo often describes how she literally “embraces” them or “dances” with them, starting on a little step next to the lump of clay, working her way up in order to shape and form them. They are literally embodied objects, providing a connection with all of humankind – Odundo says ceramics tell “the history of our humanity,” since they have been essential to all cultures.

In an exhibition currently on show at the Hepworth Wakefield in West Yorkshire, Odundo has been asked to select and combine objects and images with more than 50 of her own vessels. It is a clever curatorial strategy befitting an artist like Odundo – one sees in an instant how her work is situated in a wide web of influences and inspiration, her chosen objects and her own pieces appear almost like old friends having a conversation. On display is an eclectic variety of objects, artifacts and ideas that have influenced her vision and interests – vessels from British studio pottery, ancient Greece, and Egypt; ceramics from Africa, Asia, and Central America; Elizabethan textiles; ritual objects from Africa; and sculptures by Degas, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, and Rodin. The resonances are aesthetic and cultural but also located in shared techniques and approaches to art making.

In an interview Odundo has said that “in Nigeria, I learned to look and listen. By listening to people who made art, they made it apparent that ambition wasn’t enough to make you a potter. Patience was the vital ingredient, you had to learn to observe, to participate…”[1] It is this deeply thoughtful and humble approach to her art that sets Odundo apart; from this fusion of listening, learning, and collaborating she creates works that are at once situated in tradition, but also singular and original.

Based in London Liese Van Der Watt is a South African art writer and associate editor of C&.

[1] See http://visualarts.britishcouncil.org/exhibitions/exhibition/magdalene-odundo-ceramic-vessels-2005

More Editorial