Intersecting Patronage, Family and Community with Bernard Lumpkin

7 Janvier 2021

Magazine C&

Mots Will Furtado

4 min de lecture

After a decade of collecting artworks by artists of African descent with his husband, New York patron Bernard Lumpkin has made their collection public through a book and travelling exhibition, with a focus on community-building.

Collecting art can be a creative venture that requires a vision and a specific appreciation of aesthetics. For New York art patron Bernard Lumpkin, collecting is an integral part of his life but also, more importantly, a way to support artists in the early stages of their careers. “A good number of artists whose works I collect are part of my extended family,” he tells me via Zoom. “I know them personally, and my children have met them.”

Together with his husband Carmine D. Boccuzzi, Lumpkin started collecting a decade ago, informed by the conversations that he had with his father, an African American professor of physics, about identity, race, and what it means to be American. The collection primarily consists of works by African American artists, from Troy Michie to Kara Walker. “I began collecting art by artists of African descent as a way to engage a family story that was important for me,” says Lumpkin, whose mother was born in Morocco.

Kara Walker, Untitled, 1995. Paper collage on paper 52 x 60 3/8 in.© Kara Walker

Though collecting art is generally associated with purchasing artworks, Lumpin also sees it as supporting the development of artworks and an artist’s career in whichever way might be most adequate. “Museums are still grappling with collecting performance art, for instance, which is a medium that really belongs and thrives in an institutional context,” he explains. “And I would not collect it the same way I would a painting. It’s important for a patron to understand what the work needs, and if the work needs an institutional context then that’s where your support should go.”

This means that Lumpkin now works as facilitator and advisor, having fine-tuned these skillsets while sitting on the board of trustees of the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, as well on the education and the painting and sculpture committees at New York’s Whitney Museum, and the media and performance committee at the city’s Museum of Modern Art. “I see patronage as a way to facilitate education,” says Lumpkin. “And to build community, extending to curators and other collectors whose projects I support.”

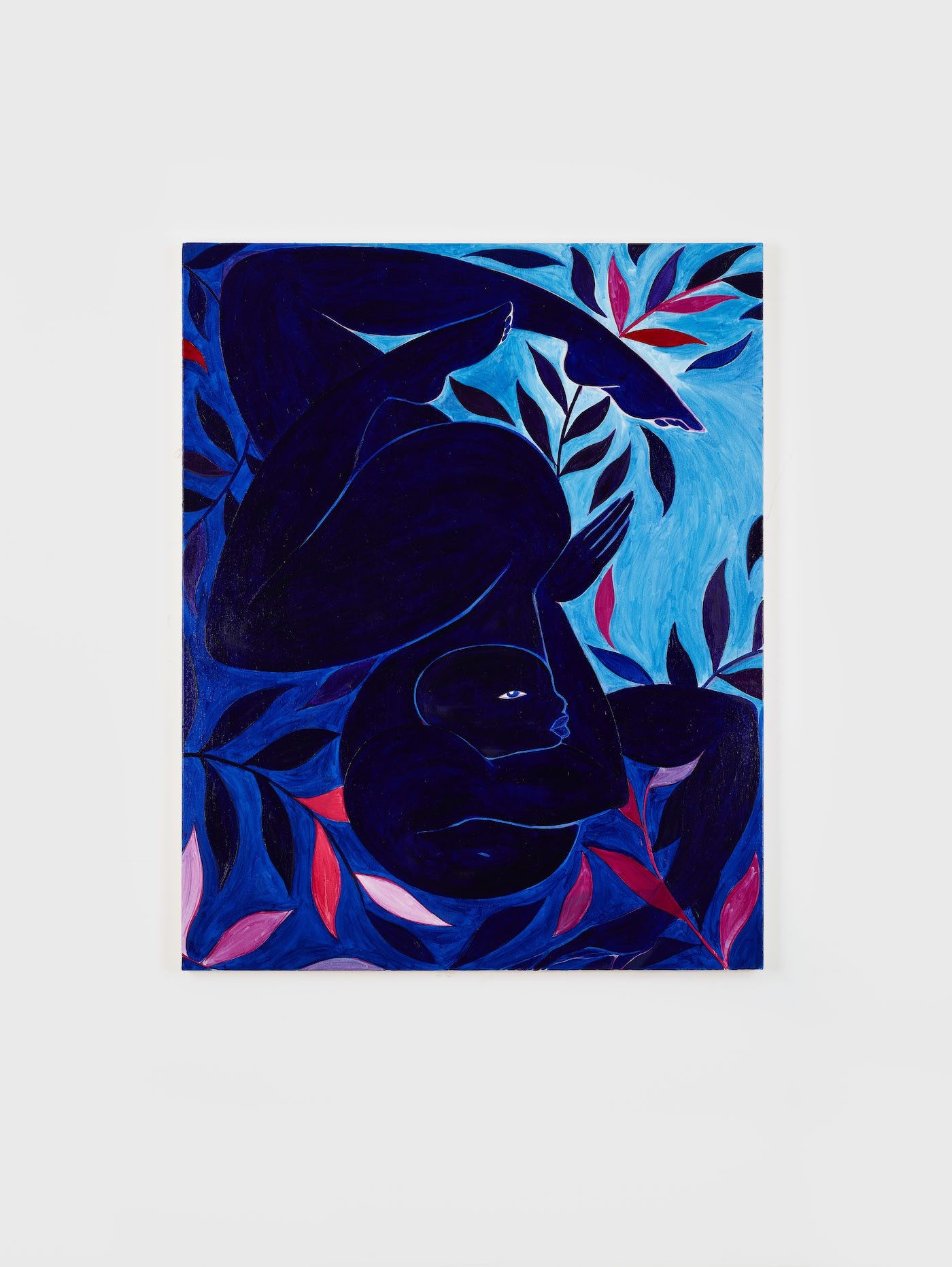

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones – Blue Dancer, 2017. Oil on canvas, 68 x 54 in. © Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

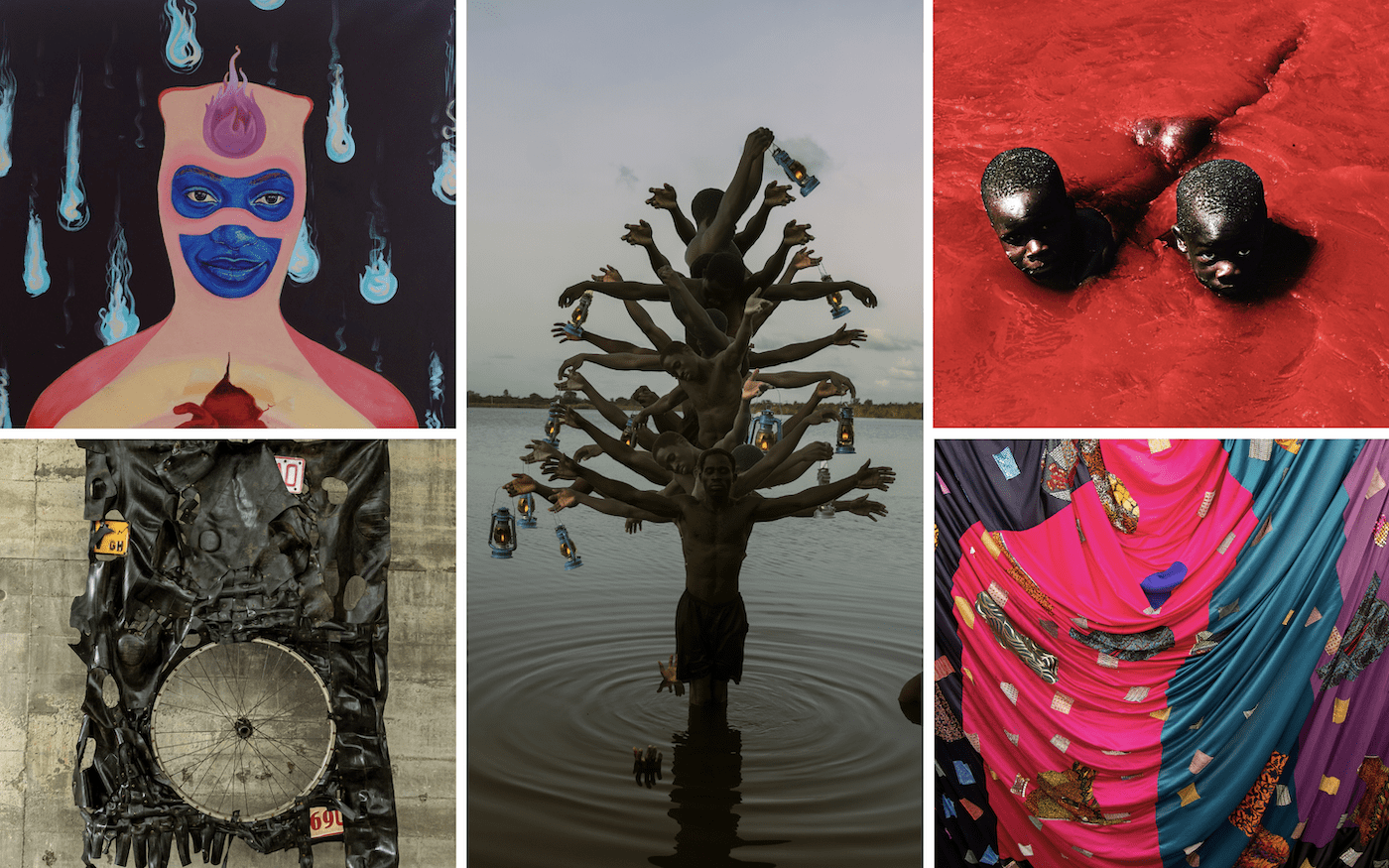

Lumpkin’s attitude towards patronage has meant that the collection has developed into a book, edited by critic Antwaun Sargent, and a travelling exhibition curated by Sargent and Matt Wycoff. The cover of the book, Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists, The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art, features a painting by Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, whose figurative works reference West African history and mythology including his own Yoruba heritage. Divided into thematic chapters, the book also includes forty-nine other artists who work across painting, installation, video, and photography and span two distinct generations—from Jacolby Satterwhite, Sable Elyse Smith, and Christina Quarles, all in their thirties, to Kerry James Marshall, now in his sixties. Also included are texts by the artists themselves and by curators such as Thomas J. Lax, and a conversation between Lumpkin and Thelma Golden.

For Lumpkin, who studied literature at Yale and made a career as a producer of news programs and educational documentaries at MTV, developing the book into a travelling exhibition was the logical next step. Its first two venues were in colleges. One of them, Lehman College Art Gallery, is situated in the Bronx, a New York area known for its working-class immigrant communities; the choice of such a venue seems in line with Lumpkin’s parents’ careers as educators.

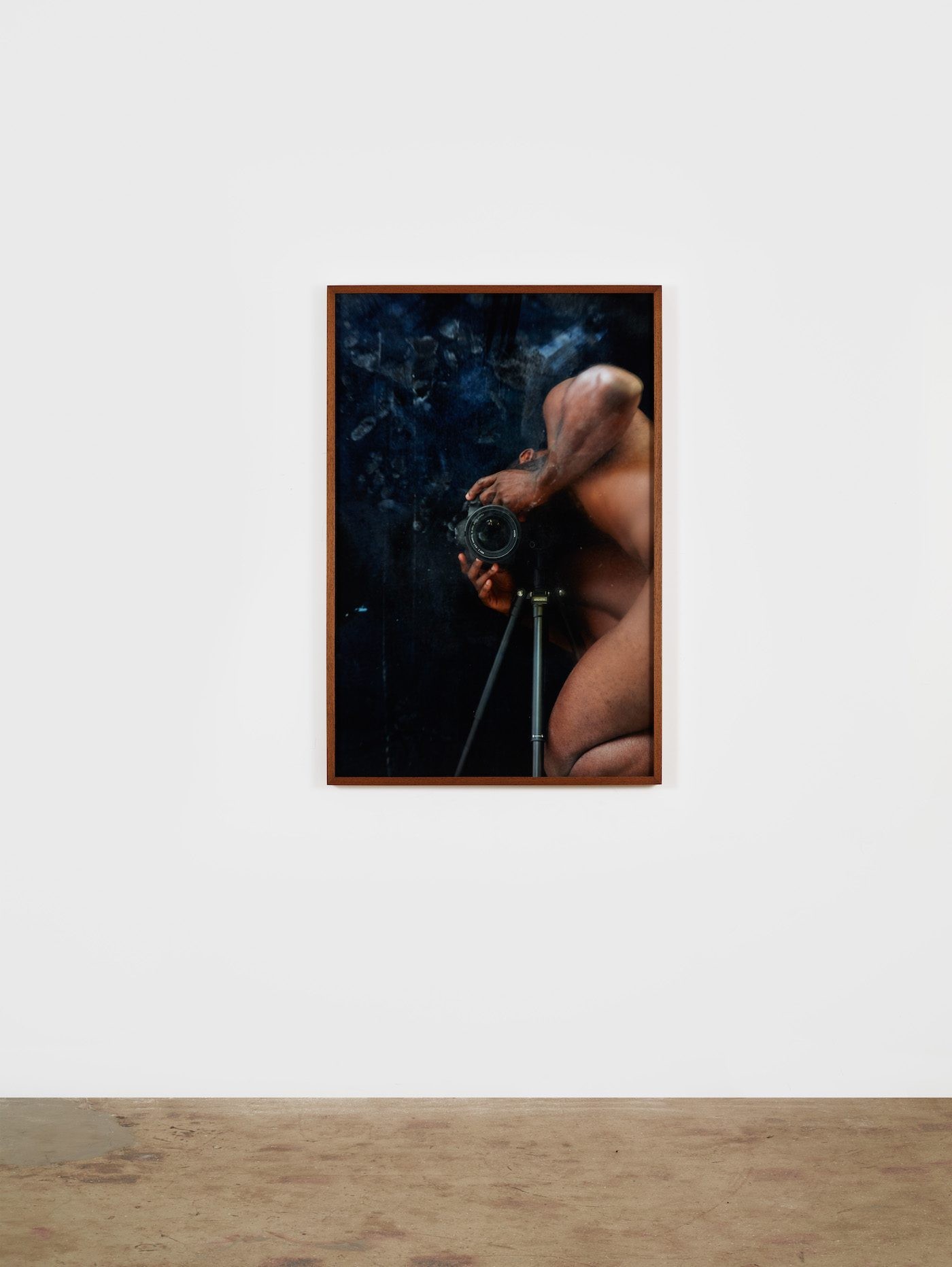

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Dark Room Mirror Study (0x5A1531), 2017. Archival pigment print51 x 34 in. © Paul Mpagi Sepuya, courtesy of the artist and team (gallery, inc.), New York

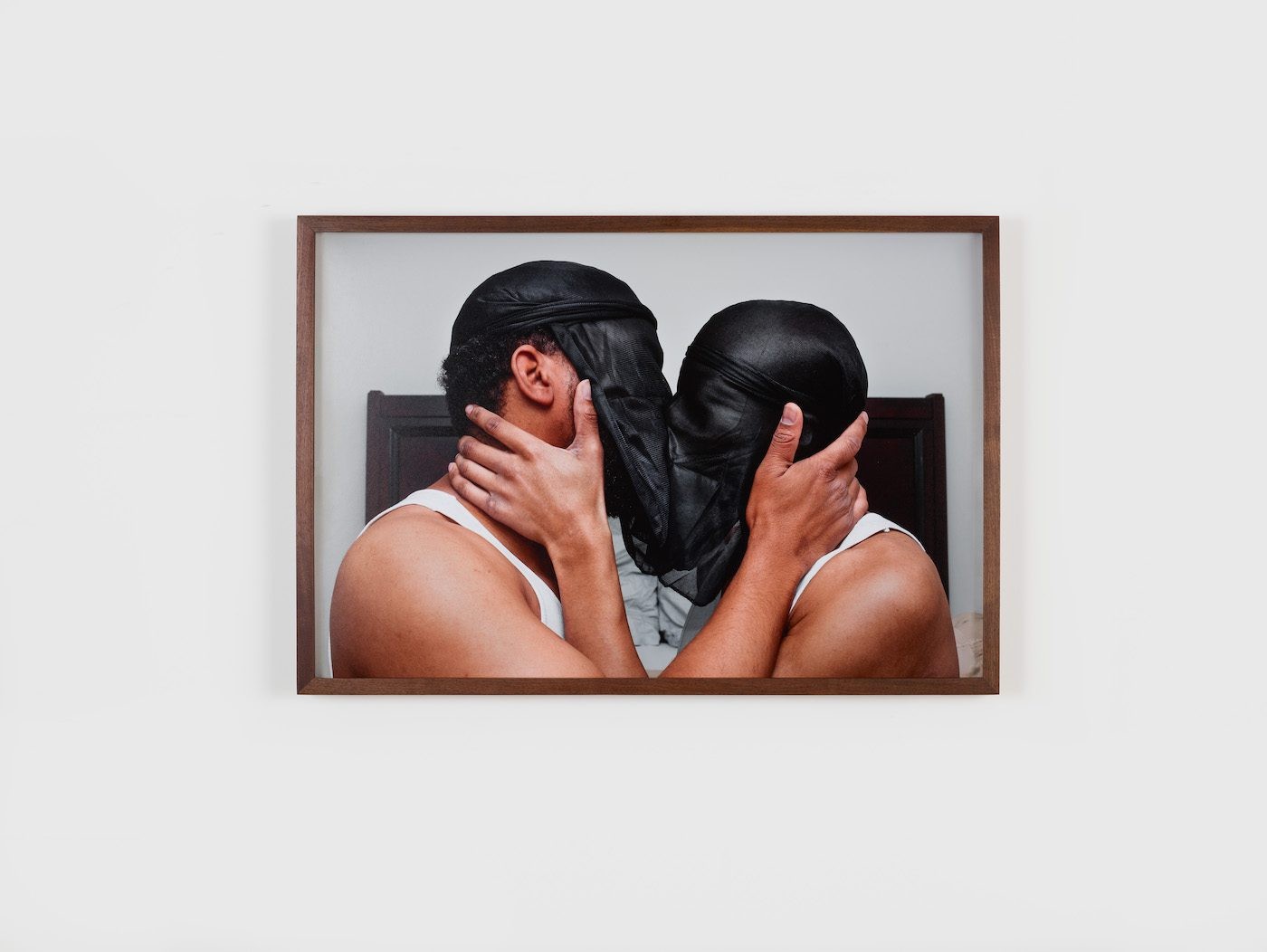

The exhibition places the works of an emerging generation of Black artists in dialogue with the work of their predecessors, while spotlighting highly experimental practices within established mediums such as painting. Color, tactility, and representations of the human body are foregrounded. Jordan Casteel’s male nude in deep black tones (Kenny, 2015) poses confidently, making a connection to the piercing gaze of the figure in Kerry James Marshall’s Den Mother (1996). Cameron Clayborn’s roompiercer with tool (2019) and toolholder (2017) sculptures add a level of material vulnerability to Deana Lawson’s theatrical portraits.

Despite the evolution of the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art, opening a dedicated museum for it not yet in the cards. But hypothetically speaking, it would have to follow contemporary discussions on equity and inclusion. “Diversity would be a top priority,” Lumpkin says. “From the staff to the board of trustees, it would have to reflect the economic and racial diversity of the community it would serve.”

The book Young, Gifted and Black is out now and the exhibition is on pause and will resume at the University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois, in September 2021.

By Will Furtado.

de

Fonction

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room : annotations sur l’art, le design et les savoirs diasporiques

de

Emerging artists

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

Emmanuel Aggrey Tieku, lauréat du Prix ellipse 2025 consacré à la scène artistique émergente du Ghana