Eric Gyamfi reflects on his activism, photography, and telling the stories of West Africa’s queer communities.

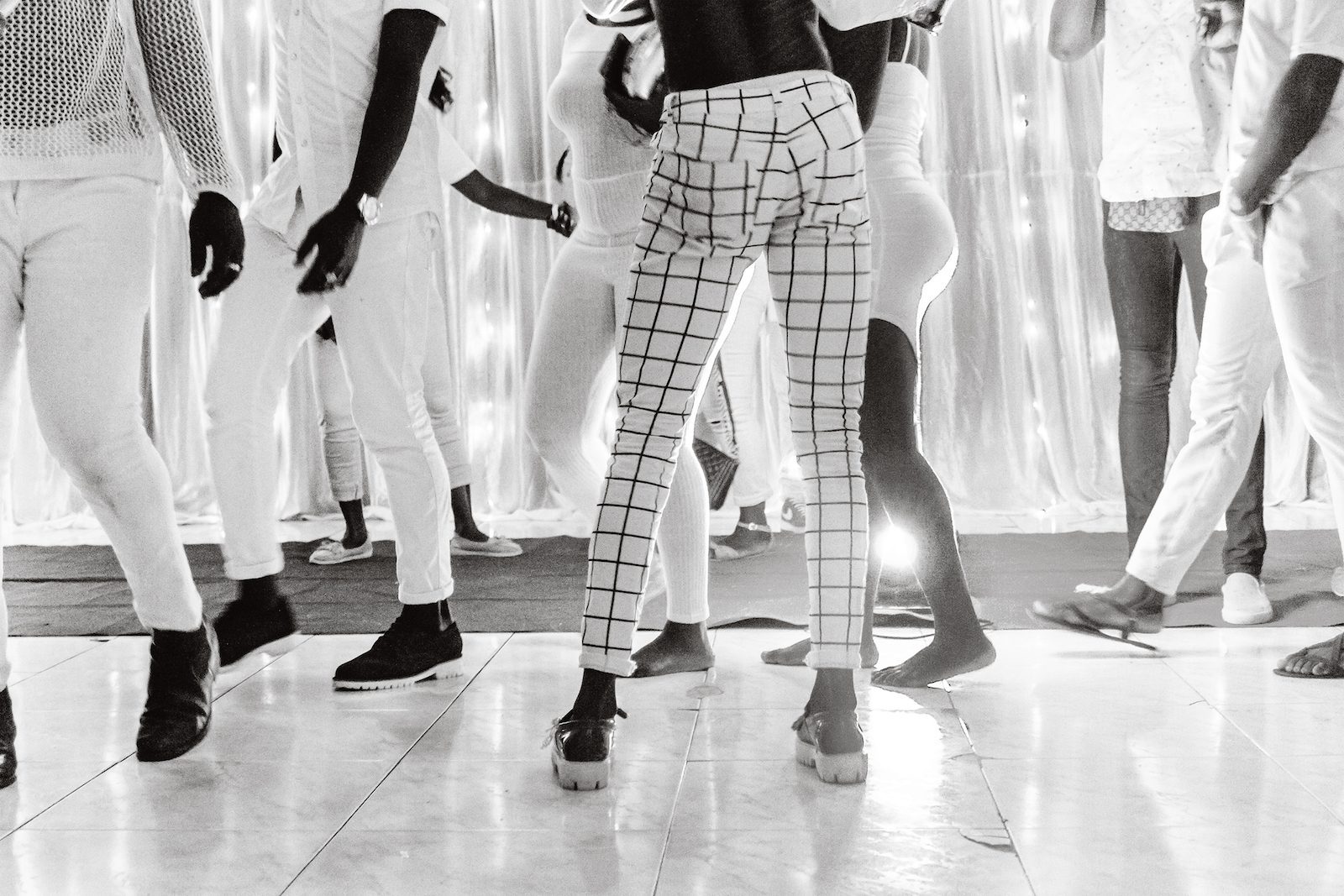

Eric Gyamfi, Some of the LGBT community members organize a night of dance and performance for themselves after the international day against homophobia and transphobia event as a way to get to know other community members and to network. From the series Just Like Us, 2016. Courtesy the artist

In his series Just Like Us (2016), the photographer Eric Gyamfi explores the contradictions of queer life in Ghana. His work chronicles what it means to be “other” in a nation of people who have a remarkably well-defined sense of what binds them together—the geographical and legal constructs that shape their national identity as Ghanaians. Just Like Us is the beginning of an open-ended journey in which Gyamfi chronicles the lives of queer friends and acquaintances, whom he calls “participants.” It’s a project that helps Ghanaians rediscover the ordinary in the face of extraordinary rumors.

Several months before I wrote about Gyamfi for “Platform Africa,” the summer issue of Aperture, I was introduced to his work at the LagosPhoto Festival. Despite the bustle of the location—a large, busy hotel in the city’s Echo Atlantic development—and despite being placed in a nook among many other works, his work stood out. And just in case I didn’t notice them, the celebrated veteran photographer Akinbode Akinbiyi made sure I would. “Watch this guy!” he said, jabbing his finger at the photographs.

My first conversation with Gyamfi took place on March 6, 2017, the day marking the sixtieth anniversary of Ghana’s independence from Britain. When he answered my message on Skype, I’d just been listening to Gyamfi’s video introduction to See You See Me (2016–17), an exhibition project at the Nubuke Foundation in Accra, which was supported by the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund. I thought, then, that I could possibly frame my Aperture essay within the context of Ghana’s Independence Day and the poetic longings for creating and being “home.” Our conversation ended at 2:59 a.m. Accra time. It was the beginning of a dialogue that helped me understand how to best introduce readers to his body of work.

Eric Gyamfi, Henry goes through some old photos. In 2011, Henry was married, and he got divorced in 2015. Henry has a son from this marriage, who is currently in the care of Henry’s mother (his son’s grandmother). From the series Just Like Us, 2016. Courtesy the artist

M. Neelika Jayawardane: In my introduction to your Aperture portfolio, I wrote that since the beginning of your career, you have “focused on individuals who have endured marginalization and exclusion.” You mentioned immediately that you didn’t want to be framed solely by your work about marginalized groups. Could you explain this choice?

Eric Gyamfi: Once there is a me and a you, everyone potentially carries the possibility of being an other. But marginalization is a very strong word. I do not feel comfortable being framed within that context as it really boxes me in. Some of these situations are difficult to explain but so many contradictions exist simultaneously and are real experiences. I am more interested in creating bridges across which we can experience realities other than our own, whether it be those of marginalized people or not.

Eric Gyamfi, Henry and his boyfriend, Mingle. From the series Just Like Us, 2016. Courtesy the artist

MNJ: As I was thinking about your work, I realized that it was important to speak about your journey as a photographer who began with explorations of the self: the memories you recreated from your childhood, positioning yourself within the re-enacted dramas of your photographs. These were the photographs, from the series Asylum, that I saw in Lagos. What was the concept behind that series?

EG: At the heart of this storytelling experience is the centrality of truth, and I am very much interested in that. When we experience the world, there is almost always a kind of filter. When we tell stories, we have to think them through. What, then, is the truth in storytelling? We say, to the storyteller, tell me what happened, tell me the story. My own memories become the starting point for interrogating this idea of the truth. Through the re-enactment process, derivative truths are created that otherwise didn’t exist, and older memories are added; I’m playing on recall, and attempting to make them true somehow in the present between shutter clicks. This exercise is also very revealing, healing even. Like being your own psychotherapist.

MNJ: You prefer to use the term queer rather than LGBTQ, as is commonly used in the U.S. In the pages of an international magazine like Aperture, you understood the importance of translating the ideas of Just Like Us for a global audience, but nuances of terminology are important to you.

EG: Yes, I have been using queer as a more inclusive term, as opposed to LGBTQ, as I feel queer has the potential to embrace people with varying sexualities, and those who wouldn’t want to fit into a neat lesbian or gay box. But I guess that’s what the “Q” at the end of LGBTQ stands for—questioning. Words and labels come with their own baggage, their own history and visual representations, and until I can properly understand and situate them, I do not feel comfortable using them.

I heard the word gay for the first time when I was in my second year of junior high school. I was twelve at the time. I remember that day very well. Fredrick, my dorm mate then, was the one who passed on this information. He said, “Abroad, men who like other men are called gay.” I understood what he meant, literally, and could connect to it. I started looking up the word on the Internet. I think that sometimes when people say that being gay is “un-African,” it is probably just the label they are referring to. Because the term has its own histories and imagery in Ghana that people may not readily relate to—or that people here feel is foreign.

So, I wanted to find out how queer people are referred to in our individual local dialects and what kinds of imagery accompany these labels. Until I heard the word gay for the first time, how did I imagine queer people? In instances where there are no labels, can we find out why? Queer—as a label—is not entirely free of these problematics. Some of my friends say that queer is cowardly and only people ashamed of their sexuality use it.

I also feel that refusing to readily define people, or putting them into these neat categories, can form a part of the solution here. You would be surprised at the kinds of relationships that exist that people do not name. It has been a part of the culture to let certain things be without labelling them. And, I dare to say, that strict labels and categories of gay, lesbian, bisexual, et cetera, have also been tools used for widespread homophobia here. Of course, queer is a label, too. But it is one that I feel has the capacity to be everything and nothing.

Eric Gyamfi, Kwasi and Annertey find the Akaa Falls. Kwasi, looking to start a magazine on Ghanaian tourism, explores the eastern regional landscape of Ghana with his friend, Annertey, for new places to feature in the debut issue of his magazine. Kwasi identifies as a gay man, Annertey as a straight man. From the series Just Like Us, 2016. Courtesy the artist

MNJ: A lot of research—meaning personal contact with the people you photograph and learning their daily routines—goes into your work. Why is this process important?

EG: I am very much interested in understanding people’s experiences; their sexualities are just one aspect of their lives. My curiosity lies predominantly in why people have the experiences they have and how different mine would be if I were to grow up under similar situations and conditioning. My approach, therefore, is to be with people, to experience life with them. It’s how I experience life for myself, too. In some instances, my work can be more about understanding myself.

Eric Gyamfi, “Someday, soon, I’d have to live as a straight man,” Jay laments, one Thursday afternoon after school as we walked. “I think about that every day.” Jay identifies as a gay man. From the series Just Like Us, 2016. Courtesy the artist

MNF: Eric, on many occasions that I’ve emailed you, you are preparing to go to or returning from a photography trip, sometimes traveling great distances. Like Zanele Muholi, you are deeply involved in your queer community; you’re an intrinsic part of this community’s well-being, be they inhabitants of the city or of rural areas.

EG: I have been interested in learning and documenting what it means to be queer here and now, and the only way to do that, for me, is by being present. I have been thinking about how active we are as participants in helping write history and what better way to do that than by contributing our lives, in visuals and literature, to the larger overall history of this place.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York–Oswego and arts contributor to Al Jazeera English.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Aperture magazine, coinciding with Aperture’s summer 2017 issue, “Platform Africa.”

More Editorial