North American artivist Mia Imani Harrison meets a new self-declared liberation movement in Hungary.

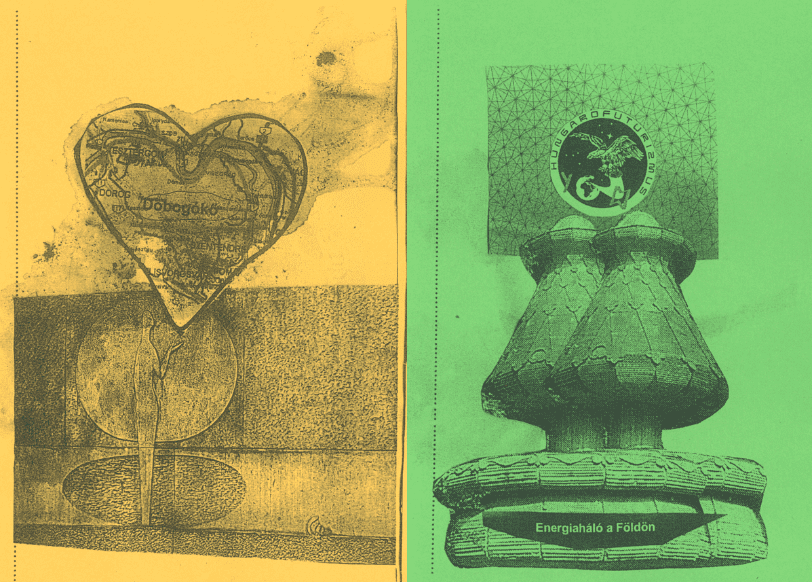

Hungarofuturism Manifesto

Last year, while most of her Black friends were more invested in the promise of healing offered by the “Year of Return,” artivist Mia Harrison was summoned on a trip to explore Eastern Europe’s new liberation movement – Hungarofuturism. In this interview Harrison talks to the Hungarofuturists about how their artistic and theoretical movement emerged and how it relates (or does not relate) to the struggles of Black and other oppressed communities reimagining the historical past and dreaming new futures.

C&: What is your role within Hungarofuturism (HUF)?

Zsolt Miklósvölgyi (editor, critic, art theorist): Together with Márió Z. Nemes, I’m a co-author of the Hungarofuturist Manifesto (2017). I prefer to define myself as a facilitator within the movement.

Orsolya Bajusz (researcher, cultural worker): A decentralized node among the many.

Márió Z. Nemes (poet, critic, academic): I am a co-author of the Hungarofuturist Manifesto. I also coined the term, so we can say that I am one of the creators of the concept. I’m interested in Hungarofuturism both in the artistic and theoretical realms. My third poetry book, A hercegprímás elsírja magát (The crying bishop, 2014), was my first attempt to deconstruct the Hungarian identity in an absurdist pseudo-historical context, and that project concluded in the creation of the Hungarofuturist vision.

Dominika Trapp (artist, doctoral student): I’m a member, co-founder of the Hungarofeminist lodge.

C&: What is Hungarofuturism? How was it created?

MZN: It is a cultural-artistic movement that attempts to rethink Hungarian national identity as freed from self-colonizing nationalist narratives. Similarly to Afrofuturism, it forms an identity-poetic experiment in radical imagination, through which an emergent minority identity can feed into a strategy of post-ironic overidentification. As opposed to the hegemonic discourse of Hungarian consciousness, it represents an alternative way of being Hungarian through discovering post-Hungarianness.

OB: HUF is about developing a highly abstract and symbolic discourse related to matters global and local, examining matters of national identity beyond liberal or nationalist identitarian scripts.

C&: How was Hungarofuturism inspired by Afrofuturism and other futurist movements?

MZN: More than mere escapism, HUF is not a rejection of the landscape but a reconfiguration of Hungarian culture within the framework of the old, building with chunks of a history that was always constructed. This specific constellation differentiates Hungarofuturism from previous incarnations of Futurism. Instead of eliminating the old and jumping forward to some kind of future utopia, HUF tries to create a time-space loop, warping history. Against revolutionary newness and passéism, HUF operates a type of spectral retrofuturism, a returning which is not quite a repetition, a strange recombinant recoded aesthetic timewarp which is also a timeswamp, complicating the deceptive simplicity of the Hungarian plains.

DT: I think it is important to state that, even if we mention Afrofuturism as an artistic inspiration, it’s obviously not appropriate to compare our struggles to the struggles of Black people. We are just middle-class Hungarian intellectuals who are critical of the current Hungarian culture war and the occupation and stigmatization of topics related to Hungarianness. Afrofuturism is a much more political movement with more serious stakes that, by carrying out a two-way time travel, formulates a fundamental critique of the present. Hungarofuturism is a political art movement that applies Afrofuturist strategies, formulating a kind of counter-narrative but in a different cultural context, directing attention to different current problems.

C&: How is trauma connected to Hungarofuturism? How does Hungarofuturism help cleanse this trauma?

ZM: HUF aims to heal the bruises of the spatial trauma caused by the loss of two thirds of Hungarian « national territory » after World War I. This « territorial loss » shifted the geopoetic imaginary of the Hungarians from the epicenter of the universe towards a peripheral hellhole. In the spirit of experimental psychogeography, HUF aspires to transcend this concentric or spherical ontology in which our political and poetic imaginations of the peripheral are trapped.

DT: In my artistic research, I deal with Hungarian peasant culture. I approach it as a model which can be the basis for a local survival strategy in a post-sustainability scenario. However, I think we should look at communities from a critical viewpoint, including their conflicts, even if we look at them as role models. In my last exhibition, I processed the recollections and trauma stories of peasant women. I examined how much room for maneuver they had in rural communities, what traumas they experienced, what traumas the community normalized, if any. Giving space to these readings of the life of the Hungarian peasantry can play an important role in obtaining a more complex picture of our culture.

C&: Who can become a Hungarofuturist? Who was the movement created for?

MZN: The Hungarianfuturist movement is open in all respects, as the source code of the concept is free. In my opinion, the question is not who can enter, but who can avoid a certain Hungarofuturization, because I envision this process as a kind of culling virus that can infiltrate anywhere.

OB: There is no central committee, so I guess no-one can really answer this question.

C&: The language used to describe the movement is often academic and connected to theory. How accessible is Hungarofuturism to the wider public?

ZM: HUF is not something you access from « outside » – it calls you from within your innermost realm. If it calls you in the language of thoughts, you answer with your mind. If it calls you in the language of love and hate, you answer with your heart.

DT: Hungarofuturism has an obviously academic language, and I do not think that those who are active in the movement want to strive for intelligibility. We are not politicians or activists, but artists and theorists. On the other hand, I am pleased to find that the spirit of Hungarofuturism has infected musicians, graphic artists, and even meme makers, proving that the movement has a quality that can be translated into a more comprehensible language.

C&: How can Hungarofuturism assist with the current state of the world, specifically Black Lives Matter and COVID-19?

DT: We don’t have a consensual opinion about these phenomena, but I personally see that the virus and its handling – although it has claimed many lives – has done a good service by making it even clearer why the system in which we live worldwide is unsustainable. This kind of situation is likely to help escalate the fight against related problems, like structural racism. As a Hungarofuturist, I welcome any movement that seeks to twist authorities and rigid, repressive structures and narratives out of place.

OB: There is more to the world than COVID and BLM. We are not the kind of movement who networks with think tanks, assumes social roles, thinks of itself as a social actor, or participates in identitarian theatrics. We precisely want to declare the HUF domain beyond such direct political involvement. Contemporary art has been instrumentalized as a toolkit to bring subjectivity into the public domain, and then to further the agenda of identity politics (mostly left).

C&: What are the next steps for Hungarofuturism?

ZM: We are preparing for an international « xenofuturities_specters_anachrony » conference on 2 and 3 October 2020 at the WUK_Museum in Vienna, Austria.

You can watch the documentation of the trip filmed by Hungarian artist János Brückner here:

Mia Imani Harrison is an artist and writer currently based in Berlin.

More Editorial