Frederick Ebenezer Okai Investigates the Possibilities of Clay

26 Octobre 2022

Magazine C&

Mots Nantume Violet

6 min de lecture

The artist’s solo exhibition explores his relationship with the earth and how his pottery is woven into the complex structures of Ghanaian society.

Contemporary And: How was the exhibition Earthy Structures and Contingent Breakthroughs conceived?

Frederick Ebenezer Okai: The title seeks to highlight my interest in soil, and how I relate to it as a living being. I am fascinated with how the material manifests in the production of objects that become part of our cultural symbolism. The title captures how these symbolic objects break out through experimentation in several installations in this exhibition.

There are nine domes, each displaying a specific work, cutting across video, installation, sculptures, sound, VR, and photography. They all stem from my interest in Indigenous pottery production in Ghana, and how its value has been underappreciated, especially among formally trained ceramicists. The university syllabus dismisses Indigenous production as requiring the least expertise and knowledge within general ceramics production.

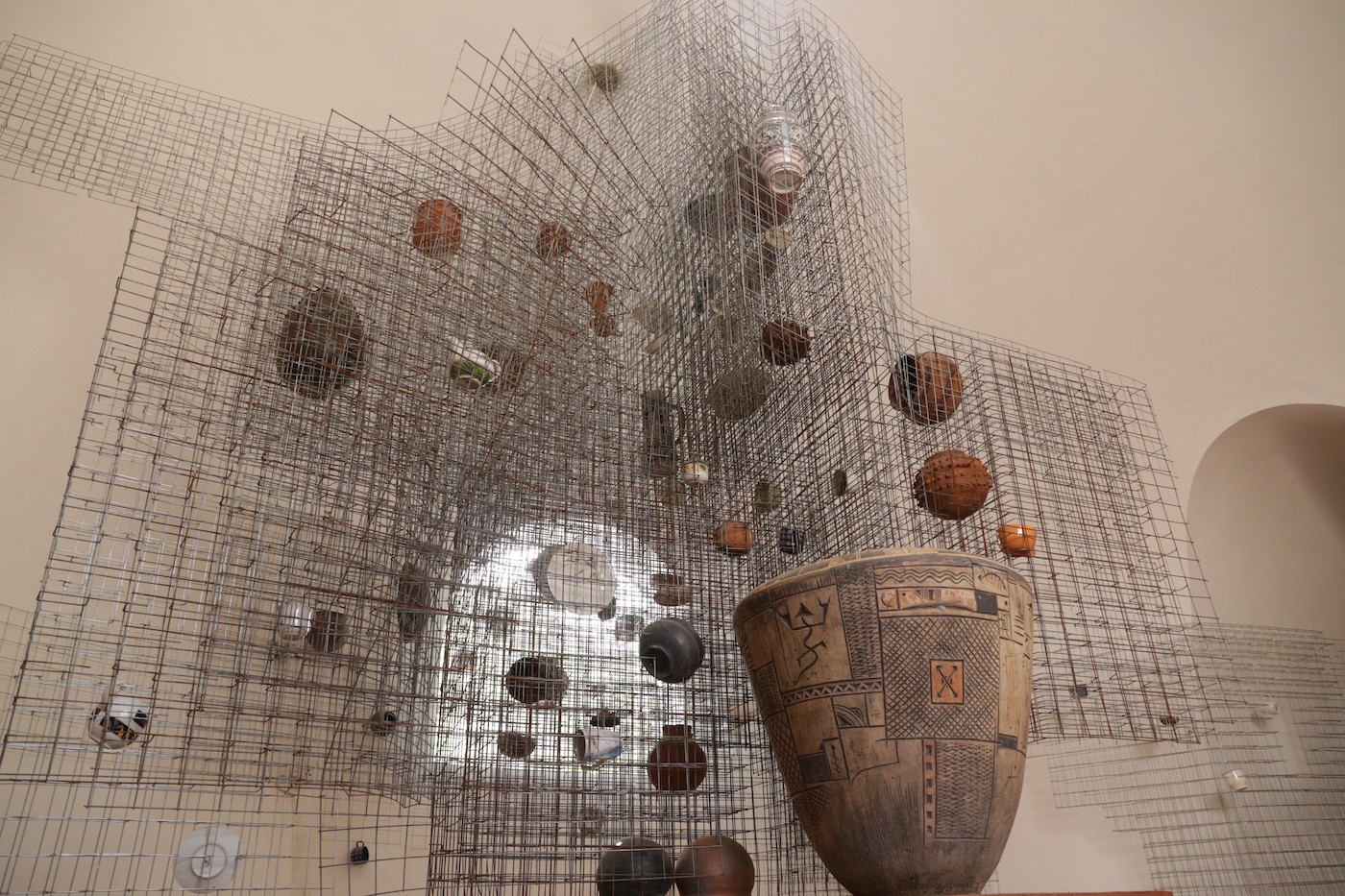

Frederick Ebenezer Okai, Obi Ara Ho Hia I, 2022. Courtesy the artist. Installation View of Earthy Structures and Contingent Breakthroughs at Gyamadudu Museum, Ghana.

C&: What is the cultural context for Indigenous ceramics practices?

F.E.O: Indigenous ceramics practice is a women-centered craft which has been passed on from mothers to daughters over centuries. The involvement of men has been quite limited and only happened rarely. In the 1940s, Michael Cardew was sent to Ghana by the British Government to teach studio ceramics at the Achimota School. He was the first artist to introduce men to the Indigenous craft. Cardew was sent to “improve the standard of pottery in Ghana” and help institutionalize ceramics. He wanted men involved in ceramics production as a source of livelihood and hoped to set up a mass production center in Ghana to supply ceramics across the West African sub-region. This is how, much later, I got the opportunity to study the art of working with clay.

My current work largely focuses on Indigenous pottery practice. I am studying the aesthetics and acquiring knowledge in its production processes and materiality. I merge it with my training in studio practice to create vessels with value beyond utility purposes. I do not rank either Indigenous pottery practice or studio practice as superior to the other. Rather, I find freedom to choose between a rich array of techniques and processes for my work.

Frederick Ebenezer Okai, When The Gods Speak, Heaven Listens, 2022. Courtesy the artist. Installation View of Earthy Structures and Contingent Breakthroughs at Gyamadudu Museum, Ghana.

C&: To what extent do you collaborate with women artists in your work?

F.E.O: I play the role of pseudo-ethnographer, moving across several communities specialized in pottery in Ghana and learning from women engaged in its production. I then fuse their collections of works with mine to create new forms.

C&: Pseudo-ethnographer?

F.E.O: I collect works of art. These objects have cultural symbolism in terms of their use. I repurpose them, recreate some pieces found in museums, especially those whose production have halted for reasons such as religion, a growing lack of interest in sustaining production cycles, and the unavailability of materials as a result of urbanization. I use strategies such as scaling sizes to heighten its form.

Nonetheless, marrying objects and styles from several communities into a single installation enables me to do away with certain ethnocentrism. I create a safe space for objects (which for me embody the human) to coexist in a single space, whether by marrying shards from rival communities into a single sculpture object or borrowing styles from diverse spaces. I make art forms that are playful and yet have significant material and historical connections that draw these objects into mainstream art.

My exhibition at Gyamadudu Museum shows a connection between the circular nature of the vessels and how the connections between the dome spaces become unending. Some of the forms are also influenced by the architectural landscape of the spaces I visit.

Frederick Ebenezer Okai, Kuruwa, 2020. Courtesy the artist. Installation View of Earthy Structures and Contingent Breakthroughs at Gyamadudu Museum, Ghana.

C&: The acoustics of the whole museum are special. Are some installations informed by it?

F.E.O: No, but an unexpected use of the acoustics was triggered by birds which, upon seeing ceramics locked inside layered galvanized wire mesh, decided to build a nest within the installation. The museum amplifies the chirping of the birds when they are present.

C&: How about the sound installations?

F.E.O: The language of the conversations varies from one box to another, including English, Dagomba, Buli, Frafra, and Twi. In some instances we used a translator. This diversity offers the chance for people from several backgrounds in search of art objects and knowledge to comprehend the conversations. The conversations are from records documented during my encounters with the indigenous women ceramists. Some have been redacted into five-minute podcasts, stored on mini-SD cards and inserted in three sound boxes. The sound boxes were built with assistance from my friend Gideon Mensah, an electronics engineer and expert in material engineering.

C&: What about the virtual reality works?

F.E.O: We scanned some of the collected objects and ran them through digital sequences, using Rhinoceros software to draw some of them as three-dimensional models. These were then fed into a Unity game engine to make a video suitable for VR modulation. With VR as an extension of my work, I am expanding the conversation about the possibilities of objects as plastic entities that can be molded into any form.

Frederick Ebenezer Okai, Obi Ara Ho Hia I, 2022. Courtesy the artist. Installation View of Earthy Structures and Contingent Breakthroughs at Gyamadudu Museum, Ghana.

C&: Please tell us about nestling some vessels in welded mesh.

F.E.O: The work titled Obi Ara Ho Hia I, which translates to “Everyone is important,” is the first of many series to come. In this piece I build my own world. It is a world where everyone is visible. I draw on the human personas attributable to pieces of pottery, situating them as personalities. Pots have descriptions such as body, neck, foot, hip. I find the uniqueness of the vessels as relational to people all over the world. It is amazing how the bird finds a place to construct its nest. The exhibition allows for these inclusions – lately, lizards are regularly seen hanging on segments of the piece.

The form of the work is also influenced by the works of architects Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid in very subtle landscapes. Its structural composition imitates humans’ endeavour to cross from the earth as a living space into other orbits, referenced through the extension of the installation into the space beyond the dome of the museum.

Frederick Ebenezer Okai’s Earthy Structures and Contingent Breakthroughs, curated by Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh, is still on view until 28th October, 2022 at Gyamadudu Museum, Kwabre-Heman, Ashanti Region in Ghana.

Nantume Violet is a curator and director at UNDER GROUND, a gallery and contemporary art space in Kampala, Uganda. She has worked as cultural producer for several years and has had collaborations in Eastern Africa, Ghana, South Africa, and Germany.

de

Indigenous art

To Spring From Salted Earth

Azu Nwagbogu: “Restitution is not restricted to objects but includes knowledge systems”

South Africa Pavilion Announces Curator, Artists and Exhibition Title for Venice Biennale 2024

de

Digital media

The Art of Dialogue: Living Archives, Memory and Practice

C& Builds a Living Digital Archive