Folding Borders

Since artist Tahir Karmali moved from Nairobi to New York, he has been exploring the impact of borders – in art and in real life. With C& he talks about his recent experiences with immigration bureaucracies, about new perspectives amongst contemporary artists in New York, and his upcoming work on materials from the Congo.

Evelyn Owen: Your recent practice has revolved around papermaking, which you use as a vehicle for exploring individual experiences of migration and its related bureaucracies. What makes papermaking such an apt process for these explorations?

Tahir Karmali: While I was applying for a visa to stay in the United States, there was a point where I wasn’t allowed to leave the country. Once you’re told that you’re not allowed to leave somewhere, you want to leave even more. I would go to the beach in the Rockaways, knowing that standing beyond this seascape are places—Africa and Europe—that I cannot access because of the papers I hold. The validation that I needed to receive was finally approved by sheets of paper and stamps.

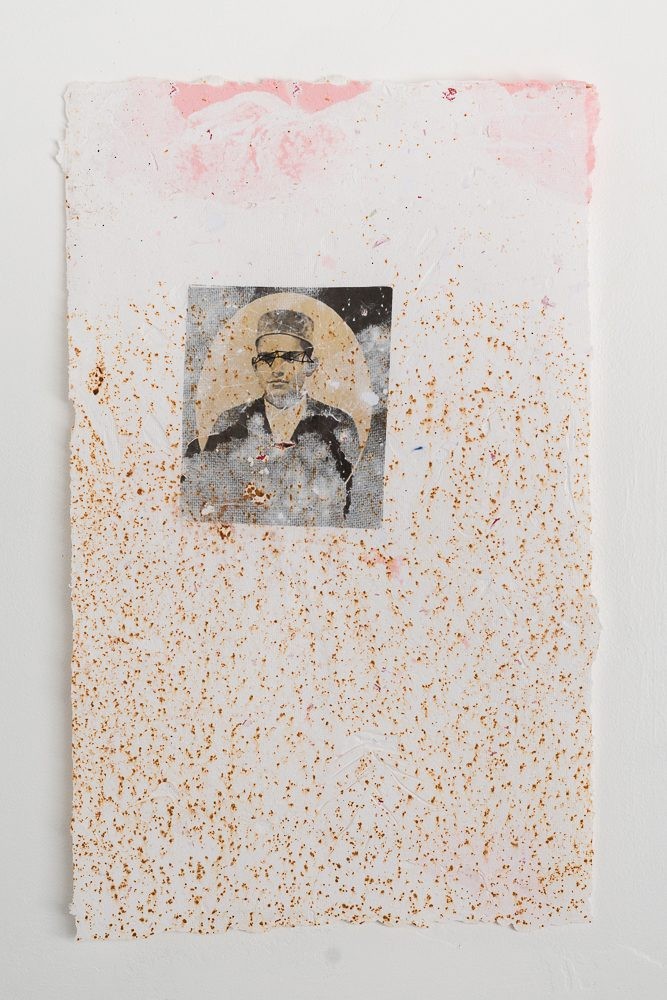

Tahir Karmali, Untitled, 2016, handmade paper made from immigration applications and photocopy toner, 13 x 23 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

The process of papermaking itself works as a metaphor for the use of paper between borders. Having the right documents allows you passage; having the incorrect documents means you’re filtered out. So I was thinking about this idea of filtering out migrants, and filtration as part of papermaking. I began to allow the paper to act naturally. And when you allow materials, especially fibrous materials like paper, to act naturally, they create landscapes—like topographic maps, or images of clouds.

EO: Were you interested in questions of migration before you moved from Kenya to the United States? And how has being in New York influenced your work?

TK: My interest in migration only emerged once I moved here. But as much as I like being part of the conversation within contemporary African art, I’m interested in transcending it and existing beyond that space. This is important in the work I’m making now, which deals with ideas of existing in certain spaces, paper, maps, geographic categorization, and so on. One part of the development and progression of an artist’s career here in New York City is to make a larger commentary, or to make work that’s not only dependent on your identity.

This gives me a lot of leeway in how to create my work. In Kenya, and a lot of other places on the African continent, it is very visual. In Nairobi, the focus was on how the work looks, and its beauty. So, moving to New York and participating in conversations about performance and painting allows me to explore more, and to say more.

Tahir Karmali, PAPER:work (installation view), 2017. Courtesy of the artist

EO: You have a residency this fall at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn. What are you working on?

TK: My current thing is materials—cobalt, raffia, and Kuba cloth—in the Congo. In a way it’s about Congo, but it’s more about the materials; cobalt as the material and visual element in phones, for example. I’m looking at these technologies and trying to distill the materials from them. I want to touch on concepts around mining for materials in African countries and how that relates to Kenya. Swahili is spoken in Lubumbashi, in the mining areas, because there are people there that come from Kenya. And I’m also interested in Kenyans’ relationships to the mobile phone industry, with Nairobi being the hub for East African technology, and Kenya the first country to ever have mobile payment platforms.

One major hurdle in creating this work, though, is the problematic sense of appropriating narratives and stories that don’t belong to me at all. In the beginning I felt that I really had no business using these tropes of raffia, cobalt, and Kuba cloth!

EO: Do you think you need a personal connection in order to be able to talk about something?

TK: Well, this is the nature of appropriation. I could obviously get away with it, because as a Kenyan I’m from Africa. In Europe they would say, “He’s African, he can discuss African things!” But is it automatically okay for me to just go across the border and discuss narratives around what happens in the Congo?

<p>

Tahir Karmali, Frankenstein’s Monster [detail, work in process], 2017, raffia, cobalt oxide and copper from phone batteries, and wood, 77 x 74 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

At the start of this process I was interested in Kuba cloth as it appears in design, especially in contemporary design. You see it all over the place: in Zara dresses, pillows, wall hangings, upholstery… So, I was considering if I was making observational work or if I was appropriating work and making a commentary about appropriation and the understanding of culture. Was I making these objects to replicate Kuba cloth? Or was I using the principles behind the making of Kuba cloth and reimagining how cobalt could interact with that? Was it my story to tell and should I be able to tell it? There was a lot of gray that I had to personally sift through and figure out.</p>

EO: How has your thinking developed as you’ve moved further into the process?

TK: I realized I was more interested in using the process element of making Kuba cloth, and less in the visual appropriation. My interest comes from a concern about disposable culture, for instance about how mobile phones and batteries are using cobalt. I am more interested in referencing land artists with my visual output, rather than Pattern- work from Kuba cloth. The cloth was a great launching platform for the process, but not from its visual appearance.

Now I am trying to make more sculptural works that address how we use process to tell stories, and how we link them to the acquisition of materials from Africa. I am working more deeply with the process. And to go back to your question about personal connection, I feel that my connection was to take an innately African process of making art, and to build on that to create contemporary work. Making objects in this way has decolonized my ideas of the art making process.

Tahir Karmali is currently a Visual Arts Resident at Pioneer Works.

Evelyn Owen is an art writer and curator based between New York City and the UK. She is currently Curatorial Fellow at The Africa Center (NYC). A cultural geographer by training, her research considers the terms of negotiation framing contested geographical imaginations, especially in relation to art from and about Africa and its Diaspora and the respective artists. She received her PhD with a thesis on the geographies of contemporary African art from Queen Mary, University of London.

En Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

En Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George