Curating reaches a wider audience

Los Angeles-based curator Jamillah James chats to C& about the state of art globally, new media, punk, the hand of the artist and Hito Steyerl’s essays

Los Angeles is building it’s reputation as a city for the visual, with new galleries opening and the promise of museum expansion, the city has a combination of epic spaces, large lots and a mixture of wealthy and entrepreneurial residents-a perfect combination for seeing art as a commodity. The Hammer Museum where Assistant CuratorJamillah James is based, offers free attendance and a democratizing approach to art. Since 2015, James has organized exhibitions and programs on behalf of the museum at Art + Practice, an organization founded by artist Mark Bradford, in a public and community engagement partnership supported by The James Irvine Foundation.

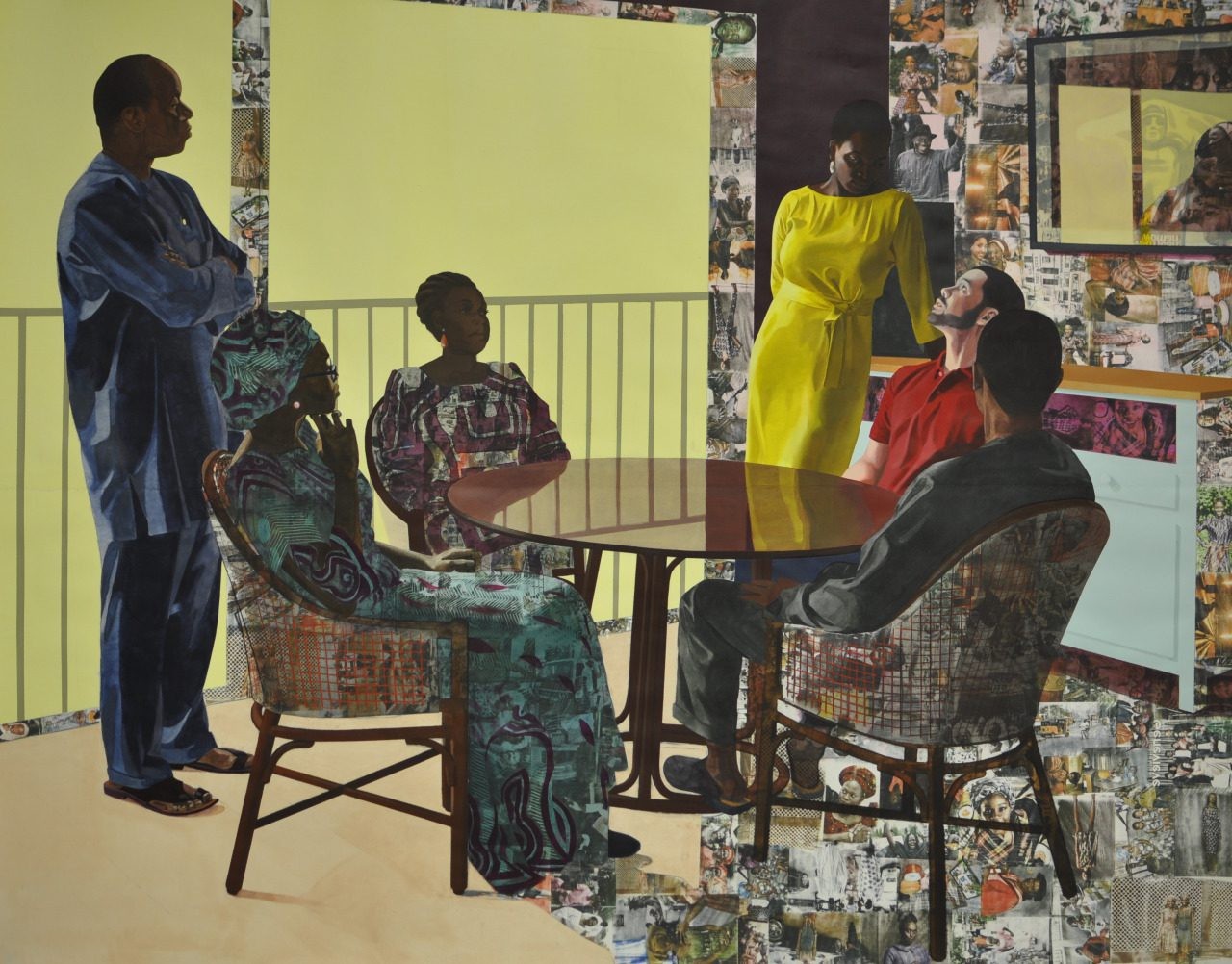

James began building her experimental and analytical eye as a teen with a focus on video and music shows. She has a thirst for the world of both visual and sonic culture and an enviably rigorous approach to curating as I witnessed in the Njideka AkunyiliCrosby show last year. The space was aglow with the tenor of the large scale figurative paintings, all gracefully positioned mimicking the poise and elegance of their subjects—a long way off from her punk-infused days.

James is brilliant, funny and winsome with a dedicated and multifarious intellect. We spoke about the state of art globally, new media, punk, her recent travels to Europe, RuPaul's Drag Race and her plans for 2016 and beyond.

Nan Collymore: Why curating?

Jamillah James: I studied Art history and Cultural studies then started working with the galleries on campus at Columbia College in Chicago. It was a combination of studying at school and setting up various events on the side that set me on the path to want to be a curator full time. I thought I would want to go in the direction of art criticism and art theory and after a while, felt that curating was something that would reach a wider audience. I guess the populist in me really wanted to illuminate the arts in a way that’s more broadly accessed.

I love working in a place like the Hammer where admission is free because it doesn’t exclude anyone. We have our regular constituents, students, there’s homeless that come occasionally and we don’t turn anyone away. I guess it’s also the punk rock/DIY ethic from being this kinda weirdo, punk rock kid who got interested in curating from programming music shows.

NC: I’ve been looking at your previous curatorial themes and I wondered why there was no photography.

JJ: I haven’t ever been interested in photography as a point of focus, but that’s not to say that I won’t at some point. My interests are ever evolving and a couple of years ago I wouldn’t have thought I would curate a show of paintings, I was primarily involved with performance and video.

My interest in painting evolved from living in New York because it’s a very painting friendly town. In terms of photographers whose work I enjoy, I like

Anne Collier, because she has a performative element in her photographs and of course Hannah Wilke, whose relationship with performance and self-portraiture relies heavily on photography. There are others, Louise Lawler, Charles Gaines—the conceptualists who extended what photography could be or do. Maybe the issue for me about photography is that there’s too much distance between the viewer and the subject in the image. It’s a representation of real life that I don’t feel terribly comfortable with.

</a> from the show Brothers and Sisters, 2014. Photography. Courtesy of Jamillah James</figure>

NC: I was surprised by how intense Akunyili Crosby’s work was. That does not come across online or in the brochure.

JJ: She doesn’t like to have her work in frames, I think with her work there are so many layers, the material, but also the richness of her story. There’s so much that goes into her work, which is very labor intensive, and you have to see it in person to see how much she’s working on it.

I really enjoy seeing process and I think I’m at this moment where new media or post-internet based work is too glib for me. I want to return to a time when you can see the hand readily in an artist’s work or see that there’s some struggle that’s happening.

NC: What do you think about the Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago?

JJ: That’s what I appreciate in artists like Mark Bradford, Theaster Gates and Rick Lowe, who are committed to making art more accessible, and have there be this porosity and engagement in different communities who may not necessarily get the opportunity to go to a museum often. To have these outposts in South Chicago, Detroit, or in South Los Angeles is really important. I know that the Frankie Knuckles house music archive is at Stony Island, which is incredibly cool, as House music is important to the history of Chicago and Detroit. It diversifies the idea of the “archive,” and what should be preserved,.It’s’s a vernacular history as important to the production of culture as slides, books, objects.

NC: Similarly with the artist-in-residence show you curated at Art+Practice (A+P).

JJ: I’m so impressed Dale and Alonzo Brockman Davis’s commitment to the artists they supported. (Speaking on the Brockman gallery archive), Dale meticulously preserved the archive in the knowledge that it would be needed. They are both national treasures.

NC: Tell me about the direction of the group show at A+P, A Shape That Stands Up.

JJ: The idea behind the show is about the possibility of having a body illustrated through a number of different forms, even if it’s not readily distinguishable as figuration. I'm interested in the idea of working in that in-between, interstitial or liminal space, and thinking about abstraction as a practice and as a way of representing corporeality. The work in the show speaks to the reality of what it means to have and represent a fracturing of the self and how this idea has a long history in visual arts. It was a considered choice to have these cross-generational conversations with emerging artists like Tschabalala Self and Torey Thornton alongside senior artists like Carroll Dunham and Amy Sillman. It was especially exciting to give the audience something unexpected by a particular artist, like two later abstract works of Robert Colescott or sculpture by Brenna Youngblood.

Installation view of The Order of Things, 2014 NC: Do you have a singular theoretical underpinning to your curatorial projects? JJ: Yes and no. I move more towards a bottom up approach. Instead of starting with a theory or impression or an idea, I let the work do the work for me, allowing that to shape the conversation. There are certain writers that I always return to and think about. Not just curators, but cultural theorists-Rosalind Krauss, David Joselit, Douglas Crimp, Michele Wallace, Hito Steyerl. Steyerl’s essay ‘In defense of poor image’ is one I go to repeatedly, even though her area is more new media. What she says in the essay has bearing on other arts - painting and sculpture, it’s important to think about the ways that we put information out into the world. Also, writings by artists and curators as well.Helen Molesworth, Connie Butler. It depends on the moment. For the Akunyili Crosby show, I read a lot of Homi Bhabha, Stuart Hall, Paul Gilroy, Kobena Mercer. For A Shape That Stands Up, I read many interviews with the artists, particularly Dunham, who is so precise about his work. Also, Amy Sillman’s many writings, Katy Siegel, Raphael Rubinstein, Yve-Alain Bois, and of course, Marcia Tucker [founding director of the New Museum, New York], whose Bad Painting exhibition is so central to this one. Still, my role as a curator is ever-evolving. My major project is first and foremost being in relationship with the artist, collaborating on realizing an exhibition (even in a group setting), rather than just being in dialogue with a book or a stack of books. . jamillahjames.com Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s two exhibitions, The Beautyful Ones and Hammer Projects: Njideka Akunyili Crosby were on view at Art + Practice and the Hammer Museum in 2015. Jamillah's recent exhibition A Shape That Stands Up is at Art +Practice was on view until June 18, 2016. Look out for upcoming exhibitions by Alex Da Corte and Simone Leigh organized by Jamillah James at both locations later this year.www.hammer.ucla.eduwww.artandpractice.org . Nan Collymore is a writer and ponderer. Materiality and embodiment are central to her work. She writes, programs art events and makes brass ornaments in Berkeley California. Born in London, she has lived stateside since 2006.

Curation

Naomi Beckwith présente l’équipe artistique qui l’accompagnera pour la documenta 16

Paula Nascimento et Angela Harutyunyan nommées commissaires de la 17ᵉ édition de la Sharjah Biennial

La Biennale de Venise 2026 suivra la vision de feu Koyo Kouoh

Visual art

Samson Mnisi: A Master Posthumously Receives His Due

Les sensibilités de Ladji Diaby en matière d'échantillonnage sont matérielles et intemporelles