nan collymore dives into the still and sophic work of Renee Gladman.

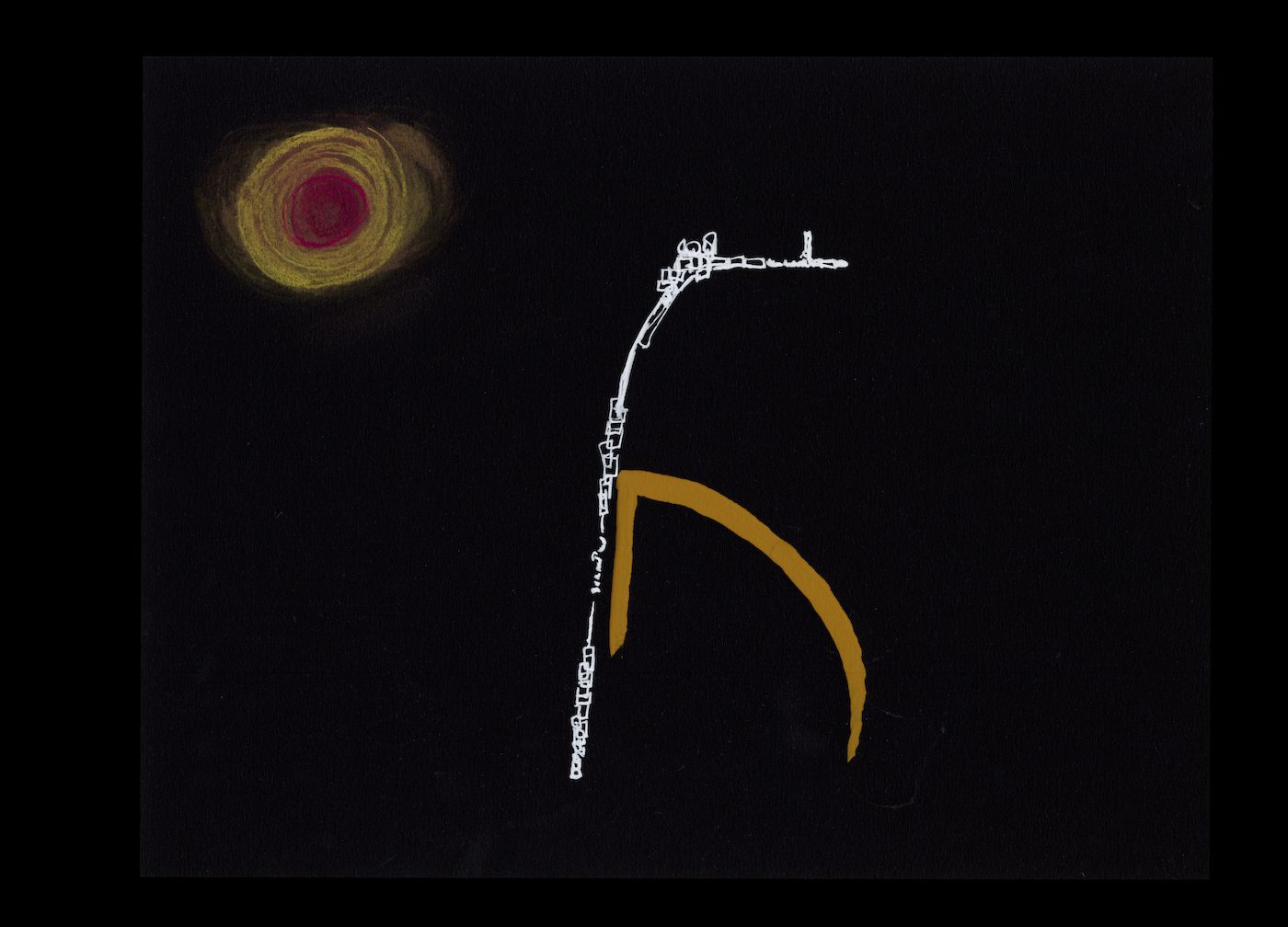

Renee Gladman, One Long Black Sentence, 2020. Courtesy and © Renee Gladman and Image Text Ithaca Press

“The problem was in the form of a question: in order to draw (was how it began), would one have to give up writing if to keep on writing one needed to draw—writing and drawing being identical gestures made with the hand—would to stop writing so as to draw make drawing impossible, since drawing was a way to think with the body and writing was the story of the body in thought?” (Calamities, Renee Gladman, 2016)

In the academic worlds that Renee Gladman and Fred Moten circle and re-imagine there is an entrenched notion of hermetically sealed arguments, of shut-off material worlds that do not intersect, yet each of their individual projects prove otherwise—that indeed there is overlap, intersection, and blur. Gladman expresses this with her new artist book One Long Black Sentence, drawing through unfolding mathematical equations, sentences, architecture, memories, and words.

Renee Gladman, One Long Black Sentence, book cover, 2020. Courtesy and © Renee Gladman and Image Text Ithaca Press

In order to embark on this pursuit of “One Long Black Sentence”, following along in their project of centering Blackand queer thought and in the spirit of deep honesty it’s important to say that until six month’s ago, I was unfamiliar with Renee Gladman’s work. In this time of extreme isolation, to be introduced to a writer/artist by the greatest of friends—who speaks to everything I have felt in my body since I began taking note of my body—feels like something to be deeply grateful for.

Before beginning the tender gesture of opening the nacreous pages of One Long Black Sentence, I succumb to the textural delights of pale stitching on black cloth. Running my fingers over the embroidered meaning, I am reminded of Nasreen Mohamedi’s words: “each wave a destiny which ends in one breath.” This is the genesis of that sentence – that long black sentence.

In her essay Untitled (Environments) (e-flux, June 2018), Gladman writes of a lineage of artists. In the essay and the drawing Plans for Sentences #88 that accompanies it, she unveils the threads of an idea—the idea of the construct of the line, it’s weaving in and out of art history and literature—centering it within a group of cross-continental women artists, a field in which I believe she belongs. The artists she cites—Nasreen Mohamedi, Agnes Martin, Mira Schendel, and others—have produced work that challenges the traditional role women have played as facilitators of craft and the domestic. Lines are commonplace in art, but somehow Gladman evokes the line as a form of spatial poiesis grounded in a Black queer feminist construction of art history, an intersecting line of women artists/a canon.

Renee Gladman, One Long Black Sentence, 2020. Courtesy and © Renee Gladman and Image Text Ithaca Press

The line and the grid become a tool of resistance, a place to embody subjectivity through negotiating differentiated notions of intimacy, touch, and the sensate—a queering of the line, if you will. Often called “asemic writing,” her drawings carry deeply codified linguistic patterns for the reader to interpret. Drawing on parallels from the ancient Andean textile language of quipu, she signals to artists like Cecilia Vicūna and Gego.

Gladman’s linguistic play recalls cityscapes and familiar places—traffic intersections, industrial sites, and bridges. She cares how the shape of a skyline holds memories and how that ties us to place. She cares how we navigate our way around bright-sunned distant horizons. And even though a place may be unfamiliar to us, a gesture or sign suggests otherwise. She is adept at arranging narrative in beautiful ways in her poetry and prose, and her drawings allow us to revisit her ideas as a somatic experience.

“I didn’t know whether at some point in my past, perhaps at the very first moment I set out to write, the page had fallen out of me or I had risen out of it.” (Calamities, 2016)

Her thinking is so still, so deliberate, “more of a bend than a break‘ (Moten), that it allows us moments to enter and carouse among the gaps and spareness of the black, endless pages. She inscribes text into drawings that Moten, in the accompanying essay, describes as “topographically complicated” with “thick” dimensionality.

Renee Gladman, One Long Black Sentence, 2020. Courtesy and © Renee Gladman and Image Text Ithaca Press

Cities she has visited, horizons she has witnessed, places she has loved, been held by, and maybe more often than not lost. Black bodies have swept among these landscapes, and her portraits are signifiers of that culturally negotiated land and space. Within these topographical visions are held the dreams and hopes of Black minds and of queer minds. That this white ink or pale brown or vivid gold might interrupt those dreams is not her intention: no, they serve as a device to further illustrate that tonal dimensionality of internal dialogue and private thought.

“What it meant to not think about place was different from never going.” (Gladman reading at Black Futures, Center for African American Poetry and Prose, University of Pittsburgh, 2018)

Studying Moten’s words, the perfect accompaniment to Gladman’s visual compositions, one is moved to a state of wonder, for one can only immerse the self in the essence of her ideas with a new language and a text that defies boundaries and categorization. At the end of the book, the way out is the anindex—adding another word in his project of creating a lexicon that fully realizes a Black landscape (or here a Blackground)—I think to mean an out of place summary for preceding signification. This curved or bent distribution of words that he assembles to somehow, some way, give direction in this “open tangle” and ask of us, “ Is a line a continuous series of point(s) that points?”

Renee Gladman, One Long Black Sentence, 2020. Courtesy and © Renee Gladman and Image Text Ithaca Press

To be sat with one of Gladman’s offerings feels like the greatest of company. Her evolution of words through drawing in One Long Black Sentence is a moment in a series of works that reflect on the shape, the bend, and the breath of words. In a recent conversation between Gladman and Moten hosted by 192 Books and Paula Cooper gallery, he called her a “beautician of the sentence.” Here, he was responding to a section of Black life in which women’s fingers create, weave, and manifest mastery over curls and how Gladman’s hands do the same for words.

I will end this beginning of an attempt to enter the book with a musical reference from 1976: Nina Simone at the Montreux festival, where her fingers, like “Tyner’s fingers don’t point, they comb” (Fred Moten), saying, “I’m meant to tell about a story, since we all have stories, but I can’t remember it anyway….” She then proceeded to play those lines, create that grid, and tell that story on the keys of the piano, deftly, with fingers frustrated by the failure of her home, her face struck by gold in the light. The lines that Gladman builds, her theory of prose architecture—splintered etches, tone, silent spectral vernacular and form—is what Nina was speaking of. It’s the discreteness that I think Gladman is seeking us to encounter in her worlds. The silent black page calls us in and causes us finally to hush—watch as we waft around those states she made for us and, in pursuit of lines, encounter ourselves as we never knew ourselves to be.

One Long Black Sentence (2020) is published by Image Text Ithaca Press and distributed by ArtBook D.A.P. Watch Renee Gladman and Fred Moten in conversation at www.paulacoopergallery-studio.com.

nan collymore is a mother an inter-disciplinary artist and an independent scholar. Her recent projects are Dress I and II, Editor of The Black Aesthetic Series III, She is Contributing Editor of Contemporary and, The September Issues and Teeth Mag.

More Editorial