Can African Critics Rewrite the Story of African Photography?

04 August 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

Words M. Neelika Jayawardane

14 min de lecture

M. Neelika Jayawardane speaks with Emmanuel Iduma about the influential role - and responsibility - of art criticism in Africa today.

Since the early 1990s, when Malian photographers Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta began to attract international attention for their stylish, midcentury portraiture, there has been an upwelling of interest in photography and lens-based media from African and African diaspora artists. Today, more than two decades after the first Rencontres de Bamako (commonly known as the Bamako Biennale), in 1994, as photography from Africa has become intrinsically tied to the global flows of art fairs, biennials, and magazines, certain geographies on the continent have remained locations of aesthetic innovation. Cities like Accra, Addis Ababa, Bamako, Cairo, Lagos, Nairobi, Dakar, Johannesburg, and Cape Town are now home to multiple exhibition platforms and educational programs, and have become centers of photography, despite financial and political pressures. Platforms and events—such as LagosPhoto in Nigeria, Addis Foto Fest in Ethiopia, RAW Material Company in Dakar, Kulte Gallery & Editions in Rabat, and the roving Àsìkò Art School and the Photographer’s Master Class—are producing their own cartographies of knowledge about art through distribution channels across Africa and beyond.

Within this ecosystem of image production, art writers play both peripheral and central roles in creating counternarratives and producing new ways of thinking about African photography. Writing about African photography has, traditionally, been the realm of an exclusive group of North American and European academics and critics. However, just as the camera, in the hands of an African photographer, produces a different image of “home,” African and African diaspora critics who write about photographs of their home produce necessary interventions in academic and critical writing. By ensuring that Africa-based and diasporic writers’ thoughts are published, we as writers create a home for our own ways of thinking about our images of self. With these thoughts in mind, I recently spoke to Emmanuel Iduma, an art writer whose work I’ve been following with deep respect for several years.

— M. Neelika Jayawardane

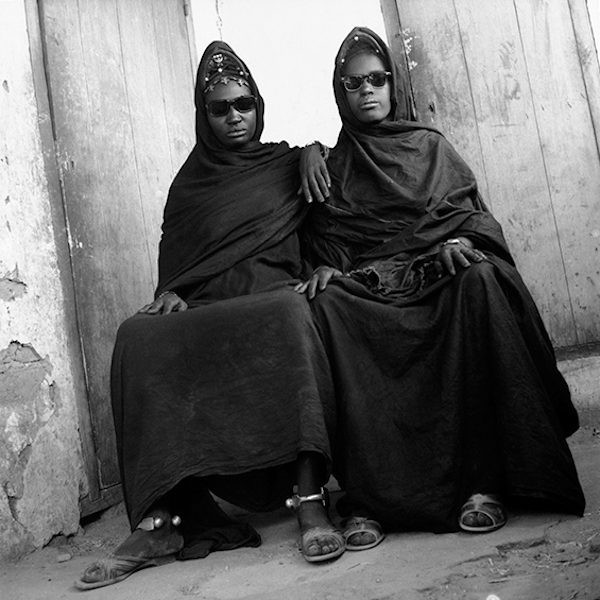

Oumar Ly, Untitled, Podor (Senegal), 1963-78. © the artist and courtesy (S)ITOR

M. Neelika Jayawardane: Last year, in a conversation at the Armory Focus: African Perspectives in New York, we spoke about writing about art. There, I wanted to open up a discussion about the role that art writers might play in enriching dialogue and shifting pervasive attitudes—in the geopolitical West—about African art and African artists, given the surge of interest in contemporary African art in recent years. You have been involved in several platforms for photography and art writing in Africa, Europe, and North America, in particular Invisible Borders and the online magazine TheTrans-African. What is your approach to writing about photography?

Emmanuel Iduma: In my writing on photography, I am probably closer to a novelist than to an art historian. I begin each essay on a photograph or a photographer with the assumption that I’m trying to tell a story, and to elucidate an experience. For instance, my essay on LagosPhoto for Aperture’s“Platform Africa” issue begins with a quote from the Nigerian novelist and playwright Sefi Atta, who asks, “Who was I to think that art could save anyone in Lagos?” The photograph, in my thinking, is connected with how it was made, where it was first published, or the event that occasioned it. What has always drawn me to thinking and writing about photographs is the sense that the people depicted are their truest selves in the light of another’s imagination—the photographer, the person who looks back. I always wonder about the tenuous relationship between image and text, especially what the text, in approaching an image, cannot unravel.

Nomusa Makhubu, Imfundo Impahla neBhayibheli (Education Apparel and the Bible), 2007/2013. Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: How people are “depicted are their truest selves in the light of another’s imagination” is a great sentence about photography! What about the long legacy of colonial ethnography, in which the colonial imagination and the regimes of fantasy surrounding the African other actually became intrinsic to colonial propaganda, scientific study, and education, and formed the basis for white supremacist ideology? Would you be able to unpack the ways in which this influential body of photography informs our own picture of ourselves?

Iduma: As writers, thinkers, and image makers, we have to be willing to confront the ambiguity of our relationship with the archive, to realize that, more often than not, our bodies were pictured in denigrating ways. And how we were seen has shaped our perception of who we are. I hope for my work to begin by engaging with this complicity, but then surpassing and counteracting it. I think now of a certain photograph by the South African artist Nomusa Makhubu, Imfundo Impahla neBhayibheli (Education Apparel and the Bible) from The Self Portraiture Project (2007/2013). In the image, she projects her silhouetted body on a colonial photograph of five men and a boy, taken by A. James Gribble in South Africa. It’s a metaphorical lodestar for me. At once repudiation as reclamation, the outline of her body is imposed on the archive; but equally, she can no longer be seen apart from it.

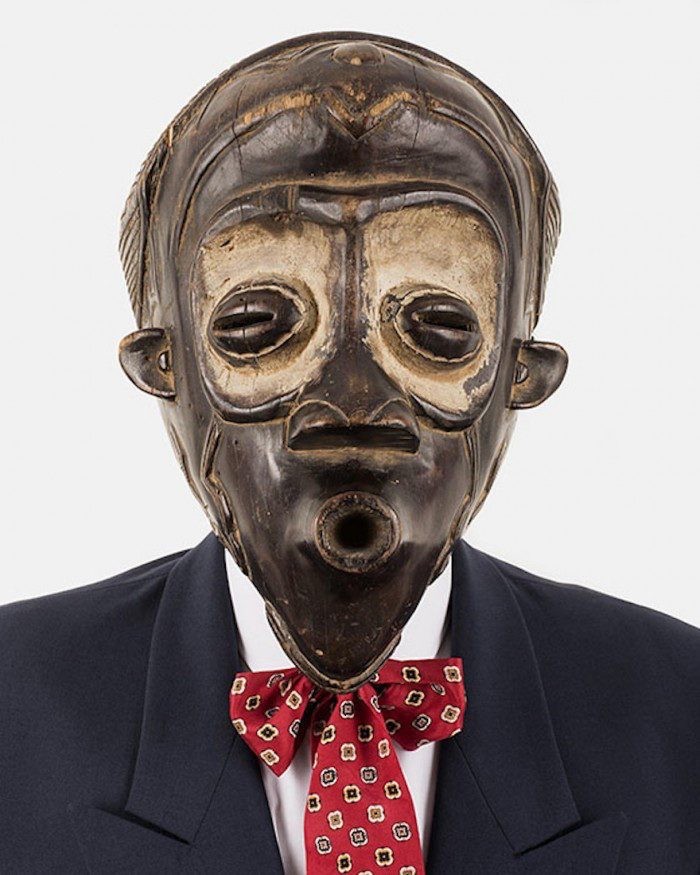

Edson Chagas, Marcel D. Traoré, Tipo Passe, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Jayawardane: Yes, Makhubu did not pick a simple archetype from colonial images. As a contemporary South African artist and academic, she is well aware of the imprint of that colonial archive on the ways in which her present body and person are “read,” seen, and acted upon, especially in the Cape. She inserts herself into the narratives handed down to us from family members and authority figures, who tell us what our collective memory should be, and draws attention to how photographs like this were used to illustrate how the “native” could be “civilized”—and made docile—through European clothing and educations. Those ideas return to us through what we today call “respectability politics”: we all, and especially young, black men, still get told that if we dress the part and behave the part, we won’t run afoul of the law, or get harassed by the state.

Shifting the center of image production is important, but it is equally important to ensure that interpretation and the critical dialogues around those images now also include writers, academics, and critics from “home spaces.” Why it is just as important for African and African diaspora writers to write about African and African diaspora photographers?

Iduma: The question is one of accessibility. How might our writing on photography reach an audience in our “home spaces?” What sort of writing style can help us achieve that? More importantly, what publications are open to that kind of writing, in which lucidity is privileged over jargon? Considered together, all three questions point to insisting on work in which the means of production is controlled by African writers, editors, and critics interested in the long-term—a fifty-year argument, I would say. It is a question of how the lineage of criticism expands from Transition to NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art to Chimurenga, from a journal that celebrates African art as an academic discipline to one in which culture takes a pan-African, mainstream bent.

And then, besides presentation, why is art writing by African and diaspora writers urgent? Is there a political necessity they express in their writing that is otherwise unclear in criticism by white writers? My inclination is to say yes. We begin our writing in response to despair we feel in our body. Art writing in any form isn’t exempt from that.

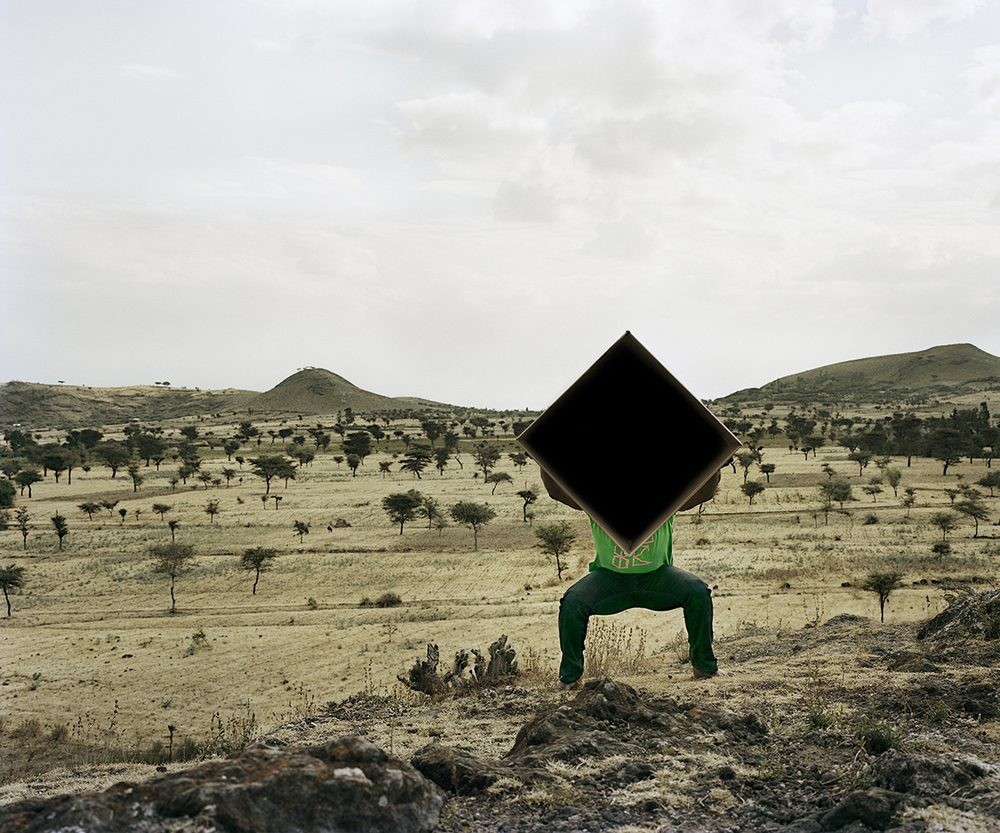

Dawit L. Petros, Single Cube Formation No. 4, Nazareth, Ethiopia, 2011. Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary, London

Jayawardane: When you write, do you begin by reading all you can find about the photographer and possibly interviewing her or him? Do you share a draft with the photographer to get feedback, or do you feel it is important that you remain autonomous? If the latter, can you speak about the importance of maintaining that autonomy and objectivity?

Iduma: I do my best to read all I can find on the photographer. However, because I have often written about photographers who are fairly young, and whose work hasn’t already received a lot of critical attention, the process of research hasn’t been as exacting. I rarely interview the photographers—I often share what I have written with them, but only at a later stage. Iwrote recently about the work of Dawit L. Petros for the exhibition catalog published to accompany his solo show at the Kansas City Art Institute. Another essay, forThe Walther Collection’s exhibition catalog Recent Histories (2017), focused on photographs by Mame-Diarra Niang, Michael Tsegaye, and Edson Chagas. For ARTNews I have written about the work of Aida Muluneh, Iké Udé, Oumar Ly, Zina Saro-Wiwa, among others.

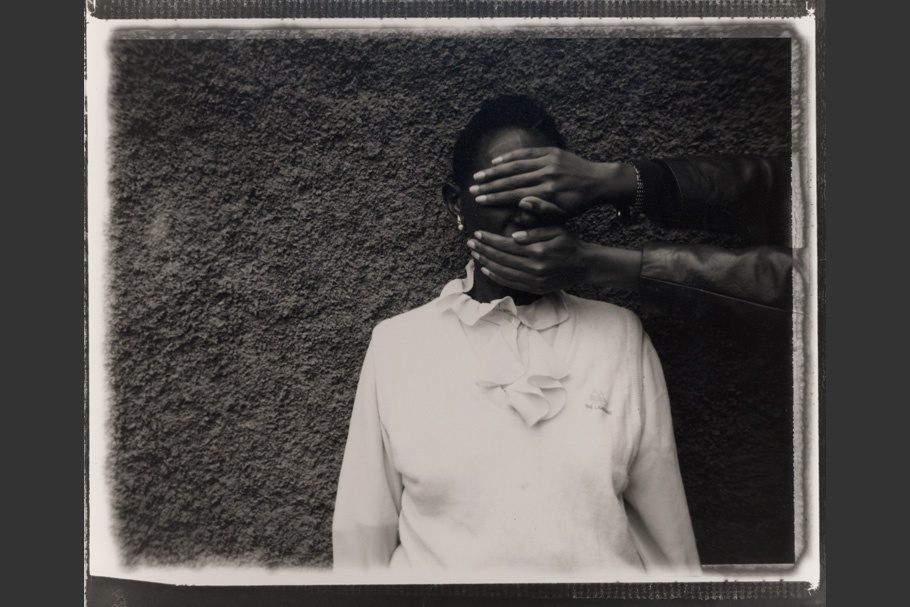

My work has also included writing on images published in newspapers and websites, which require a different kind of research. For example,“If I Could See Your Face” in the November 2016 issue of The Trans-African, or earlier in the March Issue,“Image of Displacement.” In those instances, I read almost everything I could find on the manner in which the photographs were made, and proceeded from there. I do not wish to be ignorant about those portrayed or the event depicted, but I also see the value in reaching a dead-end in the historical or journalistic record. From there I make detours, guided by the conceit of my imagination.

Like Nomusa Makhubu, I also return to images of my Nigerian forebears in the National Archives of the U.K., aware of the ethnographic, patronizing gaze of the colonial photographer. To write about those images—to respond with my experiences as a decolonizing body—is to turn the archive on its head.

Emeka Okereke and Emmanuel Iduma, A Walk in a Daraa, 2014. Courtesy the artists

Jayawardane: You have participated on several road trips withInvisible Borders, which began in 2009. Did the intimacy of that geographic journey with other writers and photographers open possibilities for creative communication? Or create conflicts that exposed the fact that people’s vastly different expectations and boundaries?

Iduma: I participated in four editions of the road trip project, each time with a different set of participants. In 2011 we traveled from Lagos to Addis Ababa; Lagos to Libreville in 2012; Lagos to Sarajevo in 2014; and, in 2016, across fourteen Nigerian states. The travels placed exacting demands on how you work and how your body responded to that work—this was a promising challenge for us, from an organizational perspective. For me, as a writer, the trips offered an opportunity to reflect on what it meant to be a stranger, to move as a stranger through African countries. But, I have been uninterested in recalling the closed lines of communication during the trips—the grouses and disagreements. I think some of that might have resulted from the nature of the project, and its constraints. Whether or not they were inevitable is a different matter.

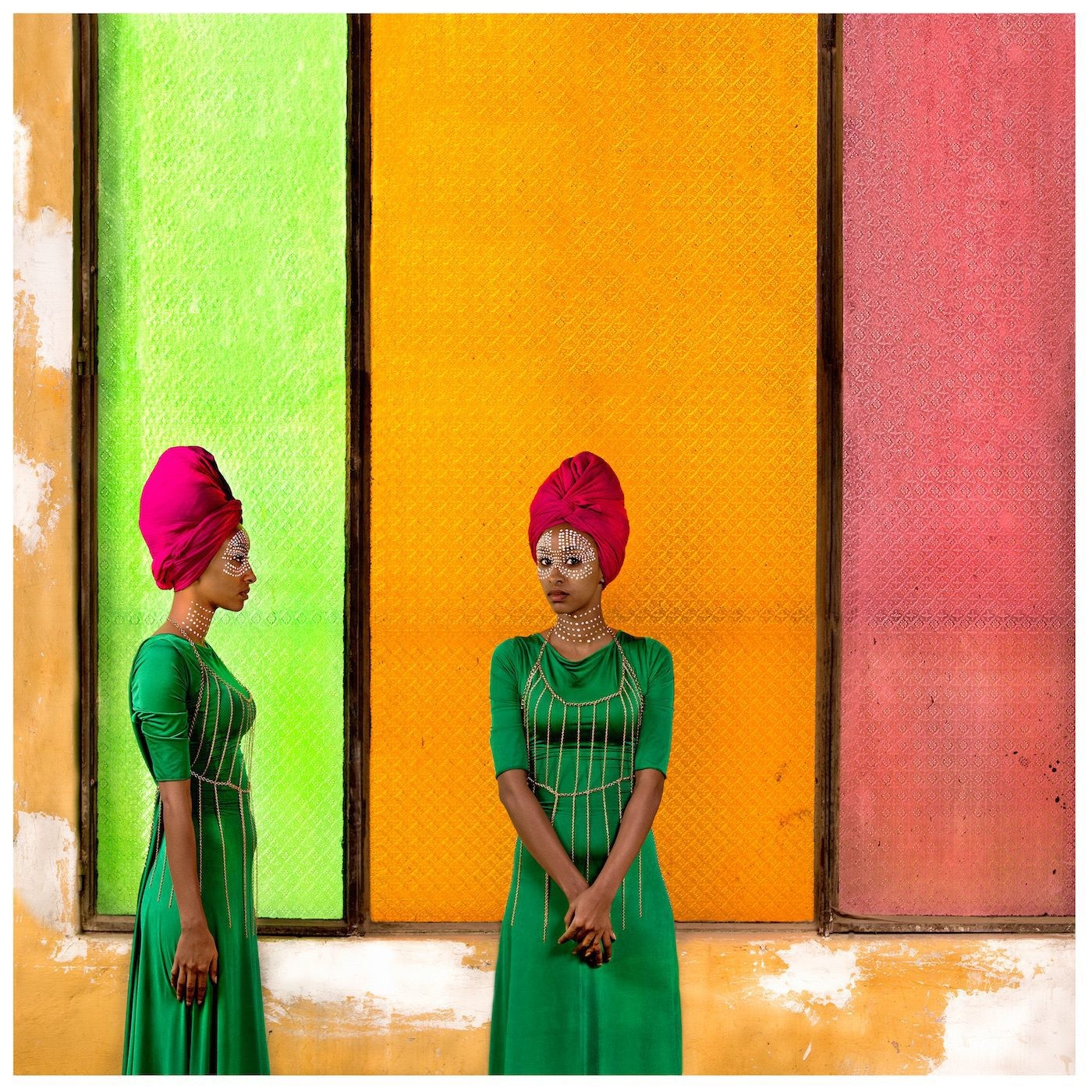

Aida Muluneh, Local Understanding, 2016. Courtesy the artist and David Krut Projects

Jayawardane: Who are the photographers or works you’ve most enjoyed writing about? Can you speak about what was enriching about these particular experiences or interactions?

Iduma: One of my favorite essays in The Trans-African is“Face in the Archive.” Since about 2012, I have spent a considerable amount of leisure time browsing the images from the Colonial Office of the National Archive onFlickr, especially those from Nigeria. One of the first images that struck me was that of three Kamberi boys, in a village somewhere in today’s northwestern Nigeria. In the photograph, a boy looks back at the camera. His glancing back bore, in my estimation, a particular anxiety. What I came up with, by the end of writing the essay, was that the task of decolonization isn’t quite done.

Eric Gottesman, Beletu, from the series If I Could See Your Face, I Would Not Need Food, 2000. Courtesy the artist

Jayawardane: The scholars and writers whose work I encountered during my literature degrees were enormously influential: James Clifford’s The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. And without Ngũgĩwa Thiong’o, and Chinua Achebe, and Edward Said to give us the language of decolonizing our own practices and minds, where would we be? Without feminist theory, I’m not sure I’d have the critical acumen necessary for speaking about why power structures and the gaze—and whose gaze—are necessary parts of a conversation about any photograph. Njabulo Ndebele’s Rediscovery of the Ordinary helped me understand that a photograph that seems to be about “nothing” contains so much.Who are some of the writers you look to? Whose writing influences you?

Iduma: I am enthused by the work Teju Cole has done in the last two years as photography critic of TheNew York Times Magazine, the rigor and reach of his essays. Maaza Mengiste has written a number of short essays on photography, some in the Guardian, which are compelling and prescient. One of my favorite books on photography is Double Negative (2011) by Ivan Vladislavić, a response to David Goldblatt’s photographs. I like to think that my work is possible because of books by John Berger and David Levi Strauss.

Emeka Okereke and Emmanuel Iduma, A Walk in a Daraa, 2014. Courtesy the artists

Jayawardane:In January 2016, you and a couple of other collaborators—fellow writers and editors Serubiri Moses and Ndinda Kioko—began a new online journal The Trans-African. It is dedicated to the reflections of independent art writers from Africa on the photographs, images, and other visual cultures of Africa. In our Armory Show conversation, you mentioned that you were interested in the work of “recuperation,” which is possible through archival work. You mentioned that the thought process as a writer is an imaginative endeavor, which does “not merely involve linear time, but time as in a dream, or a photograph.” This was especially important considering that the much of our history have a life outside archives, and outside the Web.

Iduma: “The past does not change, nor our need for it. What must change is the way of telling,” writes Anne Michaels. I wonder about a way of telling that reflects on histories that, as Brent Hayes Edwards once wrote, fell on the wayside. This work can only be done when one looks back, when the future casts its shadow on the past. Consider, for instance, the similarities in how dissident men in Nigeria are pictured upon arrest. You have General Ologbosere in 1899, Isaac Adaka Boro in 1966, and Mohammed Yusuf in 2009: all three are bound, placed between armed soldiers, and stripped to the waist. Writing about those photographs (in my essay“Regarding Insurgency”), I wasn’t particularly interested in their villainy, or the morality of their claims, but in the nature of their disillusionment with the status quo, which is a particular Nigerian anxiety. The work of recuperation is really an attempt to study the present. If we don’t cultivate skepticism for the historical record, we run the risk of perpetuating narratives tainted by colonialism and patriarchy.

Namsa Leuba, Untitled I, 2011, from the series Cocktail. Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Jayawardane: In a more recent conversation at the School of Visual Arts, you mentioned that there are “pitiably few” platforms for writing about African art outside of academia. “I knew Iwas a product of the academy in terms of my education and research interests,” you said, “but I also knew I belonged to a literary tradition invested in the mainstream, in writing that’s accessible in language and form.” Thinking about this media environment, can you speak about the significance of TheTrans-African?

Iduma: The Trans-African is a journal published by Invisible Borders. For most of last year, Moses Serubiri, Ndinda Kioko, and I published essays on visual culture. We used our home countries—Uganda, Kenya, and Nigeria, respectively—as the basis of our reflections. In July of last year, we had a three-way conversation on“Writing and The Trans-African.” It’s a good starting point to understand the guiding principles for the journal. There are thirty-plus essays on the site, which I’m proud of.

For now, the journal is on a fundraising hiatus. To put it simply: we founded the journal as a non-traditional platform for criticism. The influences for the journal are more literary than academic. By thinking through wide-ranging sources—poetry, philosophy, history, fiction—we expected our writing on visual culture, such as album covers, photographs, and film, to expand the scope of African literature.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York–Oswego and arts contributor to Al Jazeera English. Emmanuel Iduma is a Nigerian writer based in New York and editor of Saraba Magazine.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Aperture magazine, coinciding with Aperture’s summer 2017 issue, “Platform Africa.”

Plus d'articles de

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Plus d'articles de

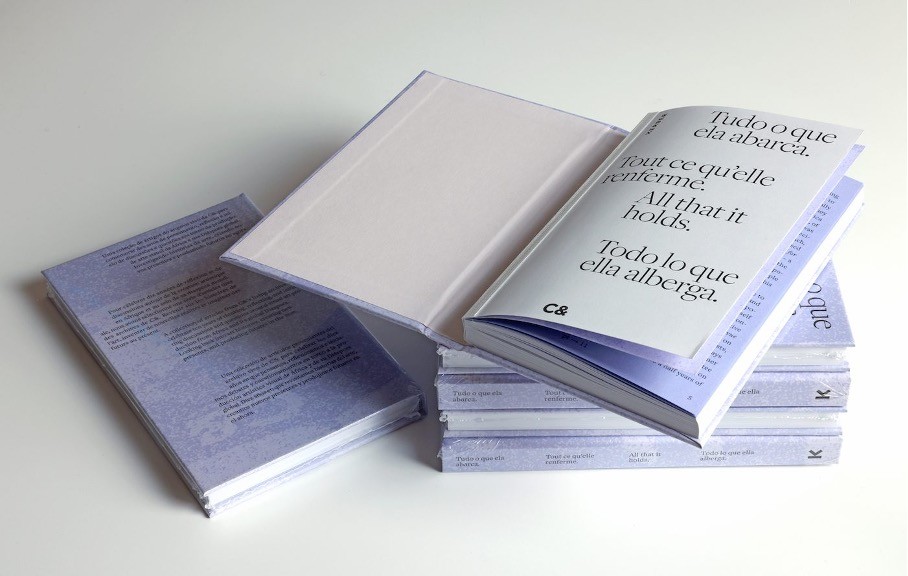

“All that it holds. Tout ce qu’elle renferme. Tudo o que ela abarca. Todo lo que ella alberga.”

C’est la Suisse, Darling