Bronwyn Katz is a South African artist working across various mediums who is interested in the notions of objects, people and spaces as lived. She is also the founder of iQhiya, an 11-women artist collective based in Cape Town and Johannesburg, and has just been announced this year’s SAM Art Projects’ artist in residence in Paris. Aïcha Diallo met the artist to discuss her interest in swapping Johannesburg for Cape Town, the dialectics between construction and deconstruction, and a cartography that is more human-oriented and less capital-driven.

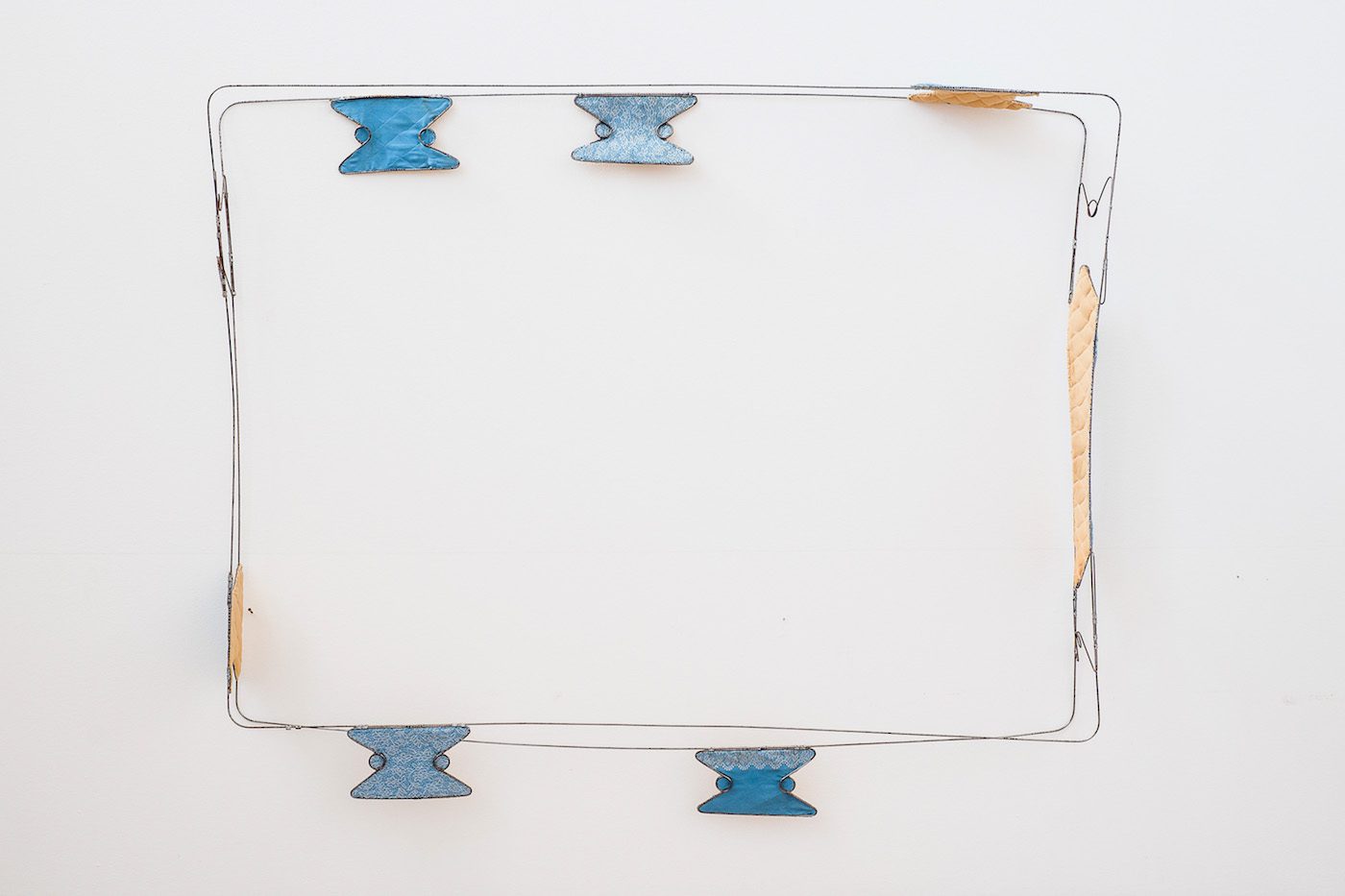

Bronwyn Katz, Wasgoed draad (2017) | Salvaged wire and mattress lining, 133 x 183 x 18 cm

C&: You recently relocated from Cape Town to Johannesburg. To what extent does this move influence your personal and artistic practice? How would you describe both art scenes?

Bronwyn Katz: I had been based in Cape Town for the last five years, mainly due to my studies at the University of Cape Town. Space and place are essential to my artistic practice and I felt that a move to another city would help expand my practice. I have been attracted to the idea of living and practicing in Johannesburg for a while now, I find the city to be exceptionally visually stimulating.

It’s still early days, and I still have much to learn about Johannesburg and its art scene. At first glance, the Johannesburg art scene seems much like Cape Town’s, the same commercial galleries operate in both cities. However, in relation to Cape Town Johannesburg appears to have a stronger culture of artist communities in the form of artist studios such as August House, the Bag Factory, Ellis House, Assemblage, etc. I think that these artist communities create more opportunities for artist-run project spaces, initiatives, and collaborations.

C&: You use a versatile range of media in your body of work. From performance to video, sculpture and installations. What kind of stories do you want to tell through your choice of materials and mediums?

BK: My process is informed by an assumed bodily trace or residue present in the materials I use in my work. The inscriptions present in these materials are my points of entry into my memory and other imagined memories. I trace and attempt to read inscriptions or residue. The dialectics between construction and deconstruction, remembering and forgetting and how these concepts work in tandem with each other feed into the physical manifestations of my work.

Bronwyn Katz, My naam is n plek,’n huis, grond (2017) | Salvaged wire; (left) 183 x 92 x 48 cm, (right) 183 x 92 x 9cm; installation dimensions variable

C&: Grondskryf – which translated literally means geography – is the newest work you showed at blank projects last October. What kinds of ideas did you seek to map out in these installations?

BK: Grondskryf is a continuation of my previous works with salvaged beds. Most of the material for the work was sourced in Johannesburg. The city is rapidly getting gentrified, which results in many poor people being forcefully removed from their homes. I collected multiple abandoned wire bed frames and bed springs from street corners in Johannesburg CBD. The salvaged wire frames and springs allowed the work to take the form of sculptural drawings. I am interested in the possibility of these sculptural drawings being read as markers of movement (forced or voluntary) or markers of space or place having been occupied.

C&: And how would you create your own personal cartography if you could project yourself into the future?

BK: I imagine a type of cartography that is more human-oriented and less capital-driven. Cartography or geographical mark making that is primarily informed by the occupants of the spaces being mapped out. Space making that seeks to dismantle social and political imbalances instead of the current types of planning and architecture which perpetuate the displacement of marginalized and poor people.

iQhiya, The Portrait, performance at Athens School of Fine Arts, documenta 14. Photo: Stathis Mamalakis

C&: You navigate between your individual practice and your involvement with the artist collective iQhiya. How do both parts nurture one another?

BK: iQhiya, which directly refers to a head wrap/ head covering, was formed by myself and ten other Black women artists (Asemahle Ntonti, Buhlebezwe Siwani, Bonolo Kavula, Charity Kelapile, Lungiswa Gqunta, Pinky Mayeng, Sethembile Msezane, Sisipho Ngodwana, Thandiwe Msebenzi, and Thuli Gamedze). It is a support structure/network for our individual and collective artistic practices. Belonging to a community of Black women artists is essential in an art world which often subordinates the practices and experiences of Black women.

C&: Finally, who are your role models?

BK: Otobong Nkanga, iQhiya, Berni Searle, Kealeboga Ramaru, FAKA, Donna Kukama, Angel-Ho, Dineo Bopape, Koleka Putuma, Jody Brand, and many more. These are all people or collectives who are bending and reshaping knowledge/meaning making in their respective fields.

Aïcha Diallo is joint Director of the art education program KontextSchule, affiliated with the UdK/University of the Arts, Berlin, and is Associate Editor of Contemporary And(C&).

More Editorial