Art Outside the Canon Box

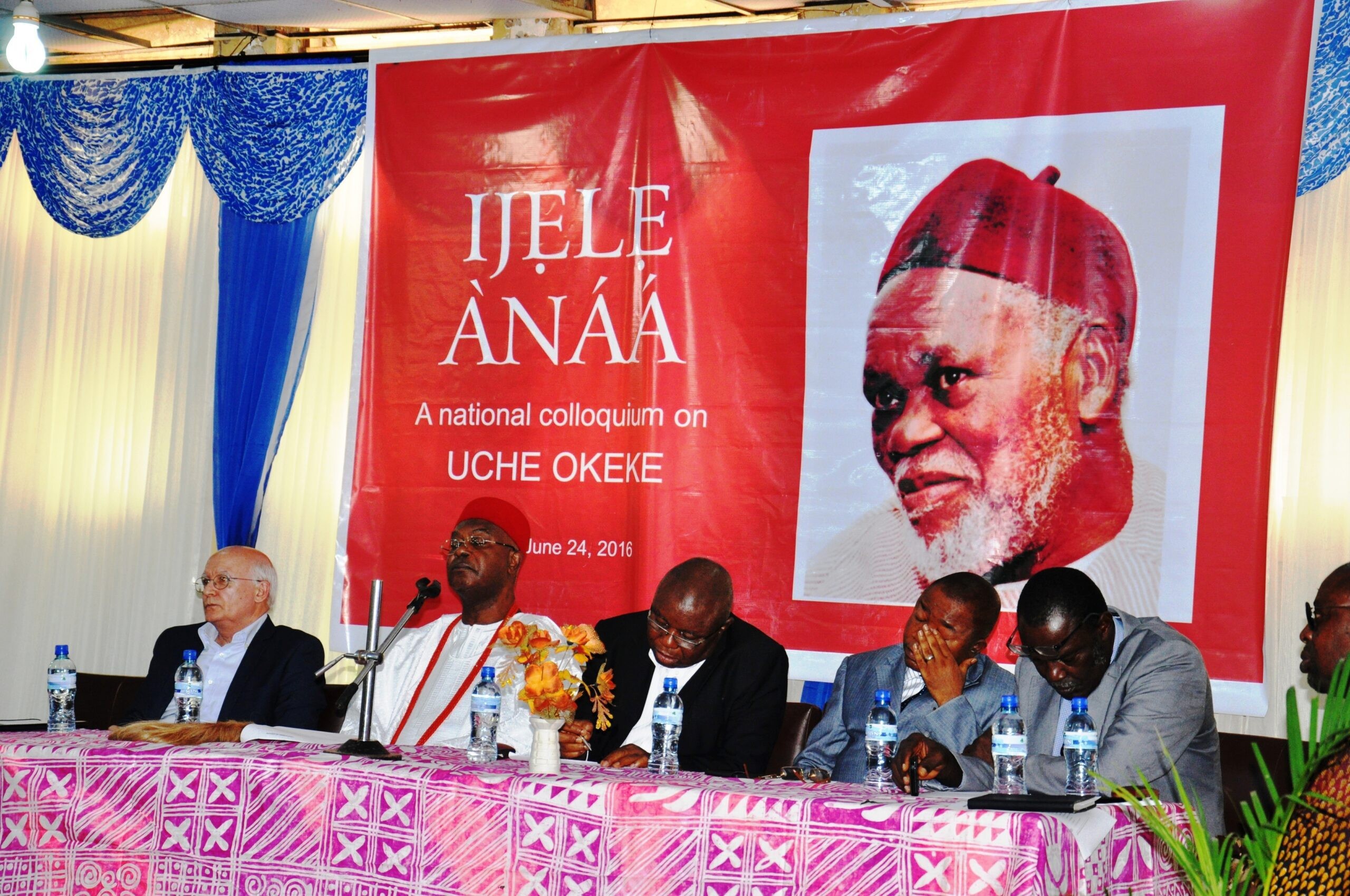

A colloquium in honor of the late Uche Okeke reexamined his contributions to modern Nigerian art. Rereading Uche Okeke today, it becomes obvious once again how he helped make indigenous art part of an established arts canon.

.

Uche Okeke had a pivotal role in redesigning the art curriculum at the University of Nigeriaat a time when indigenous artwas on the fringe of many people’s global artistic map.His fusion of traditional Igbo Uli body and wall art within academic circles is now legendary.Uli developed into an idiolect within a few decadesamong teachers and students at the Nsukka school of art.But it was Okeke’s powerful momentum that transformed it into a veritable visual languagewhose canons are spinally connected to the creative philosophy of natural synthesis.This philosophy was propounded by the Zaria Art Society, an organization formed by Okeke and his contemporaries in 1958, while they were still students.They had always wanted to push their aspiration to find more meaning in indigenous ideas without repudiating foreign influences.

As they adopted of this philosophy, Nigeria’s multiple ethnicities provoked divergent interpretations in their artistic works. For Okeke, it was Uli. As a result of the Nigerian postcolonial crisis from the mid-sixties to 1970, he had to relocate to his homeland in the then secessionist state of Biafra. His appointment to the university faculty at the end of the war became an opportunity for him to extend his creative philosophy through teaching. The foundation for Nigeria’s contemporary art had been laid with contributions of British expatriate art teachers and by Okeke’s forebears, who had been trained partly in Nigeria by European teachers and later in European art schools. They embraced concepts that were but transitory pulsations of pre-independence Nigeria.Through research, Okeke constructed experiences that exposed him to the significant players in the art and culture of the fifties.

The exigencies of the struggle for political independence required renegotiating socio-cultural content in the aim of retaining of indigenous values. This rhetoric was also entangled in the writings and literature of the era’s political matrix. An evaluation of these struggles reveals Okeke’s deep yearning for the politics behind the immortality of art as the instrument that keeps histories alive. He and his contemporaries saw in their art the capacity and tendency to mitigate the corrosive effects of colonialism without rejecting its relevant values.The result is the preservation of valuable heritage from decimation, as well as a philosophy that could sustain the process of decolonization in mid-century Nigerian art and beyond.

Okeke’s postulations and creative work are greatly relevant to the traditions of his people and its acquired modernity. They are an addition to the power, diversity, and circumambiency of a contemporary art world under the influences of globalization. Artists now come from the uniqueness of their cultural pedestals to the world stage with new artistic solutions and answers, bringing fresh perspectives through which art is enriched.What was the difference between Okeke’s natural synthesis in Nigeria and Pablo Picasso’s contexts behind the infusion of African formalism gleaned from the anthropological museums in Europe to derive his revolutionary style, Cubism?While Okeke and his contemporaries may have sought to use art and culture as tools for politics of decolonization, Pablo Picasso and other proponents of cubism were purely responding to the fluidity and flexibility common in most artists when confronted by strong influences.

The gains of Okeke’s theories and art pedagogy have strongly influenced Nigeria’s art world. It has become clearly relevant even beyond national borders, since indigenous influences are no longer restricted to anthropological leanings, but hinge on the specific artistic merits of works of art. Okeke’s work in redesigning the future of art curricula in a forward-looking manner is instructive. “For art is the soul of heritage, and heritage thrives on transition, change, and continuity if it must remain the tool for the conversations between generations,” says Chuu Krydz Ikwuemesi.According to the art critic and lecturer, it is imperative for artists of all climes “like the Sankofa, the mythical Ghanaian bird, to travel back from the future now and again to fertilize the present with the waters of the past.”

Though the Nsukka art school was founded in 1961, it was when Okeke joined the department in 1970, after the Nigerian Civil War, that the university’s standing in fine art became widely recognized.As Head of Department, he recruited talents who shared his ideology to drive his artistic vision.Among them, El Anatsui and Ola Oloidi (now professors emeritus) received honors for their contributions to this vision. Though Uli imagery is the patterning that women draw and paint on their bodies and on house and shrine walls among the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria, the artwork also included Nsibidi signs from neighboring Ibibio tribes to the south.Ghana-born Anatsui also introduced patterns from his Ewe tribe in Ghana. For over four decades, the Uli style of expression has drawn local and international visibility as it has been shown in many places such as Skoto Gallery in New York (1995) and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. (1997). At various levels, Obiora Udechukwu, Chike Aniakor, Chuu Krydz Ikwuemesi, and many others have expanded the style through their work and publications, giving the institution a unique voice.

In the twenty-first century, the aggregation of indigenous art currents in mainstream art world is propelling creativity and broadening the space and reach for people previously termed “ethnic” artists. Art, real art from any part of the world, can now occupy an equal pedestal. The world has taken more steps forward since Okeke’s Zarianist period.

.

Agwu Enekwachi (MFA) is a sculptor and art teacher. He participated in the British Council–funded Culture Journalism Workshop organized by Contemporary And in Lagos, 2015.

Fonction

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room : annotations sur l’art, le design et les savoirs diasporiques

Fonction

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025