A conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Simon Castets & Missla Libsekal about their project 89plus.

Haroon Gunn-Salie. One day my kittens will return, 2012. Courtesy the artist.

“Whose voices represent half of the world’s population?” asks cultural journalist Missla Libsekal in Another Africa’s 89plus interview series. “Those born in 1989 and later.” Her statement, which forms part of the introduction to the web based magazine’s interview series is an appropriate reminder of the momentous significance of what she terms “digital natives” the world over. It ultimately reinforces one of the key reasons for the interest of the 89plus programme in this generation, and those yet to come.

89plus is a long-term, international, multi-platform research project co-founded by Simon Castets and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Using 1989 and its paradigm-shifting events –notably the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the introduction of the Internet – as a departure point, the project explores the “relationship between these world-changing events and creative production at large”, says Libsekal. It has become a platform to “introduce the work of some of this generation’s most inspiring protagonists”.

Project milestones include the inaugural 89plus Marathon at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London and an exhibition titled, ‘89plus/Poetry will be made by all!’ at the LUMA foundation in Zurich. Additionally, the project continues to present an on-going residency at the Google Institute in Paris. And, it was their suggestion to present the project at Design Indaba Cape Town 2014 that brought 89plus to Africa.

Here, Obrist and Castets were able to collaborate with Another Africa on the first instalment of the 89plus sojourn in Africa. The collaboration manifested as a panel discussion with Obrist, Castets, Libsekal and South African artists Haroon Gunn-Salie, Jody Brand, Kyla Philander, Bogosi Sekhukhuni and Victoria Wigzell.

All these artists subsequently participated in a series of interviews, published by Another Africa. The interviews offer a deeper insight into their practices, their thoughts on growing up with the Internet and what it means to form part of a post-apartheid generation in South Africa. Houghton Kinsman caught up with Obrist, Castets and Libsekal to chat more about their collaboration, the impact of 89plus and where this project is headed next on the continent.

Houghton Kinsman (HK): It is a year since your presentation at Design Indaba in 2014. Please describe your thoughts on the contribution of 89plus to emerging practice in South Africa?

Simon Castets & Hans Ulrich Obrist (SCHUO): Because 89plus is such a long-term project, it’s too early to draw conclusions about the 89plus generation as a whole. With that said, there are certainly some very bright individual voices coming from this generation. One example is Haroon Gunn-Salie, who raises strong notions such as the transformative power of art, of participatory art within marginalised communities, and the democratization of information. Another very interesting artist is Bogosi Sekhukhuni, whose recent work has been concerned with the exchange between our virtual experiences and our physical selves, and what this means for future visual and cultural practices.

Haroon Gunn-Salie. No mans land, 2013. Courtesy of the artist

Missla Libsekal (ML): As Simon and Hans Ulrich mentioned, it’s still early days, so patterns are opaque. On an anecdotal level what struck me, based on my interactions with the five artists, was their expanded notion of public space and audience, encompassing both digital and physical realities. Notably how and why they engage outside of the white cube/gallery space. Whether it was Kyla Philander mentioning that an important tool to commune with other brown women, young women in the township, was through Twitter. Or Jody Brand explaining the role and importance of publishing her art photography online to make it accessible and therefore more democratic than a gallery, or Haroon Gunn-Salie’s project Zonnebloem Renamed that deals with social injustice and urbanisation. His unauthorised artistic intervention to return street signs back to their former name of District Six, are a reminder of the forced removals during apartheid that continue to have large impact to this day. So I share Simon and Hans Ulrich’s enthusiasm on what is yet to come from this generation. These five individuals reflect not only the possibilities but also the reality of art’s importance to contemporary living, its capacity to humanise and deal with the harsh legacies of trauma which South Africa and the continent at large faces.

HK: The presentation at Design Indaba was the first iteration of 89plus on the African continent. Why did you choose South Africa as a starting point? Why not Luanda, Lagos or Casablanca?

SCHUO: 89plus is most certainly interested in each and every African country, and indeed every country worldwide. South Africa is a particularly interesting place to start, because the 89plus generation here has essentially grown up ‘post-apartheid’ and it is very interesting to see things from their perspective. We are hoping to do more projects throughout Africa in 2015 and beyond. 89plus is a long-term project, so this is only the beginning.

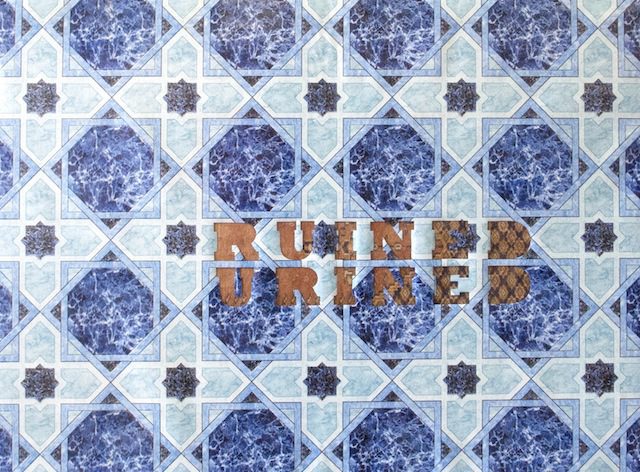

Victoria Wigzell. Ruined, Urined, 2012. Courtesy of the artist

HK: The presentation was also an opportunity for 89plus to work with Another Africa. How did this collaboration arise?

SCHUO: We initially worked together on the 89plus Panel at the 2014 Design Indaba Conference in Cape Town, to which we were invited by Ravi Naidoo, and in which Another Africa played a key advisory role for researching and selecting participants for the panel. This then developed into a collaborative interview series with the panellists.

ML: Almost a year earlier, over a cup of coffee in New York and a speedy tour of several galleries in the Lower East Side with Simon and Hans Ulrich. They are both very charismatic individuals and their enthusiasm for this young generation of talent (under 26) was infectious. I am always on the look out for talent to write about and introduce on Another Africa, and whilst I was familiar with numerous artists – I realised that many were in their late twenties and older. So this was a good opportunity to join forces to focus on a group that are at this point in their careers, less visible.

HK: Did you have any collaborative goals going into the project?

SCHUO: Our collaborative goal was to pool our knowledge and resources to provide an international platform for this generation, which accounts for more than half the world’s population, and up to 68% in some African countries.

ML: One of the positions behind 89plus is a relationship between world-changing events and creative production. So, for instance, the global transition into a digital era. In South Africa the median age is 25.7; half of its citizens were born either at the tail end of apartheid or form part of the “born free” generation. Our goal was to present a discursive approach to begin to see and understand what ideas, concerns and creative manifestations are coming from this generation that has grown up with numerous significant world-changes on the local and global level.

Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Dream Diary 1, 2013, video (still). Duration: 01.32. Courtesy of the artist

HK: Did you find any correlation or differences between post-internet artists working in places like China, America or Europe, and those working in a South African context?

SCHUO: It is too early to draw conclusions about South African artists from the 89plus generation as a whole, in comparison to other nationalities. Our prediction, however, is that the internet’s extreme globalizing force will allow for more and more connections and correlations, even though local specificities flourish and are even encouraged by cross-pollinations on a global scale.

ML: I believe Bogosi Sekhukhuni said it well in our interview, that location is not necessarily a(n artistic) concern unless it is.

HK: Moving forward, how do you envision the growth of 89plus over the coming years, especially in countries across Africa?

SCHUO: We believe that residencies are extremely important, and we hope to develop a series of residencies within Africa and abroad, to provide invaluable opportunities for artistic and cultural exchange for creative practitioners from all fields and of all nationalities. Stay tuned to 89plus.com for future announcements about projects in Africa.

HK: Does the future hold any further possibilities for collaboration between Another Africa and 89plus?

SCHUO: The interview series with the Design Indaba panellists is part of an on-going series, which we hope to recommence very soon. Another Africa and 89plus share similar philosophies about contemporary creative production, particularly in terms of maintaining an interdisciplinary approach, so we certainly hope to continue our collaboration in the future.

ML: That reminds of something written by Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher: “And what wine is so sparkling, what so fragrant, what so intoxicating, as possibility!”

Houghton Kinsman is a creative/educator based in Cape Town and Miami and has worked as the Assistant to the Curator of Education at the Museum of Contemporary Art Miami. He contributes regularly to Highsnobiety and Art South Africa magazines.

More Editorial