Norway portrays itself as an open, liberal, and tolerant country, says C& writer Sheila Feruzi. Last year she was one of fifteen participants at the triennial Bergen Assembly who made prints while discussing their experience of Afro-Norwegian identity. Her account of inclusion and diversity paints a different picture from the widely known image of Norway.

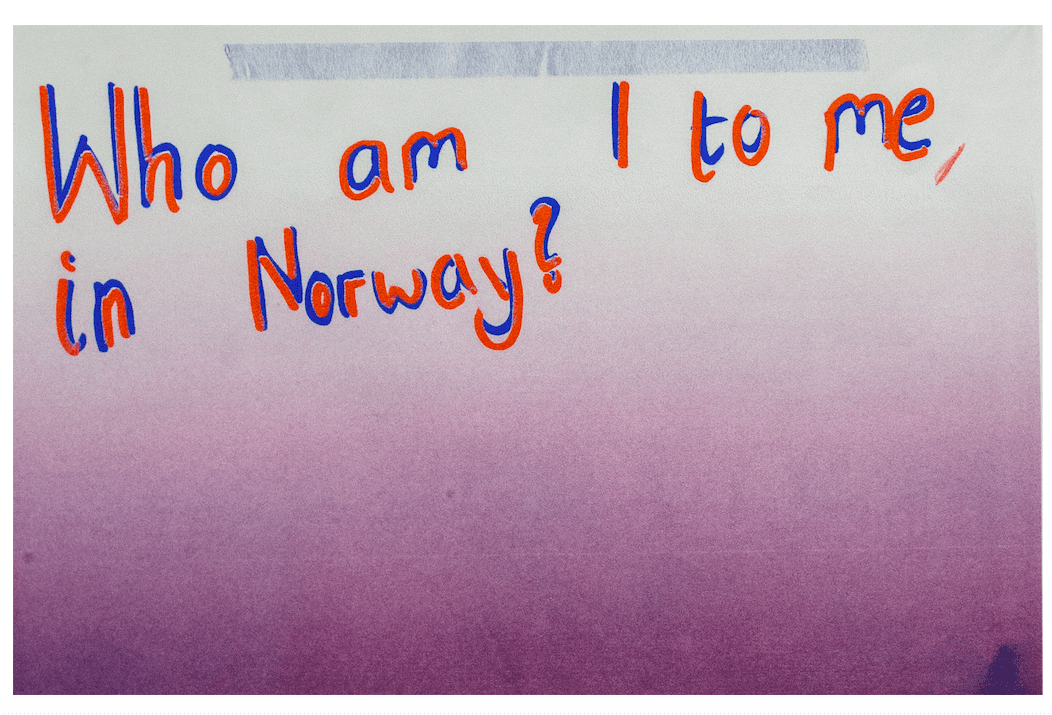

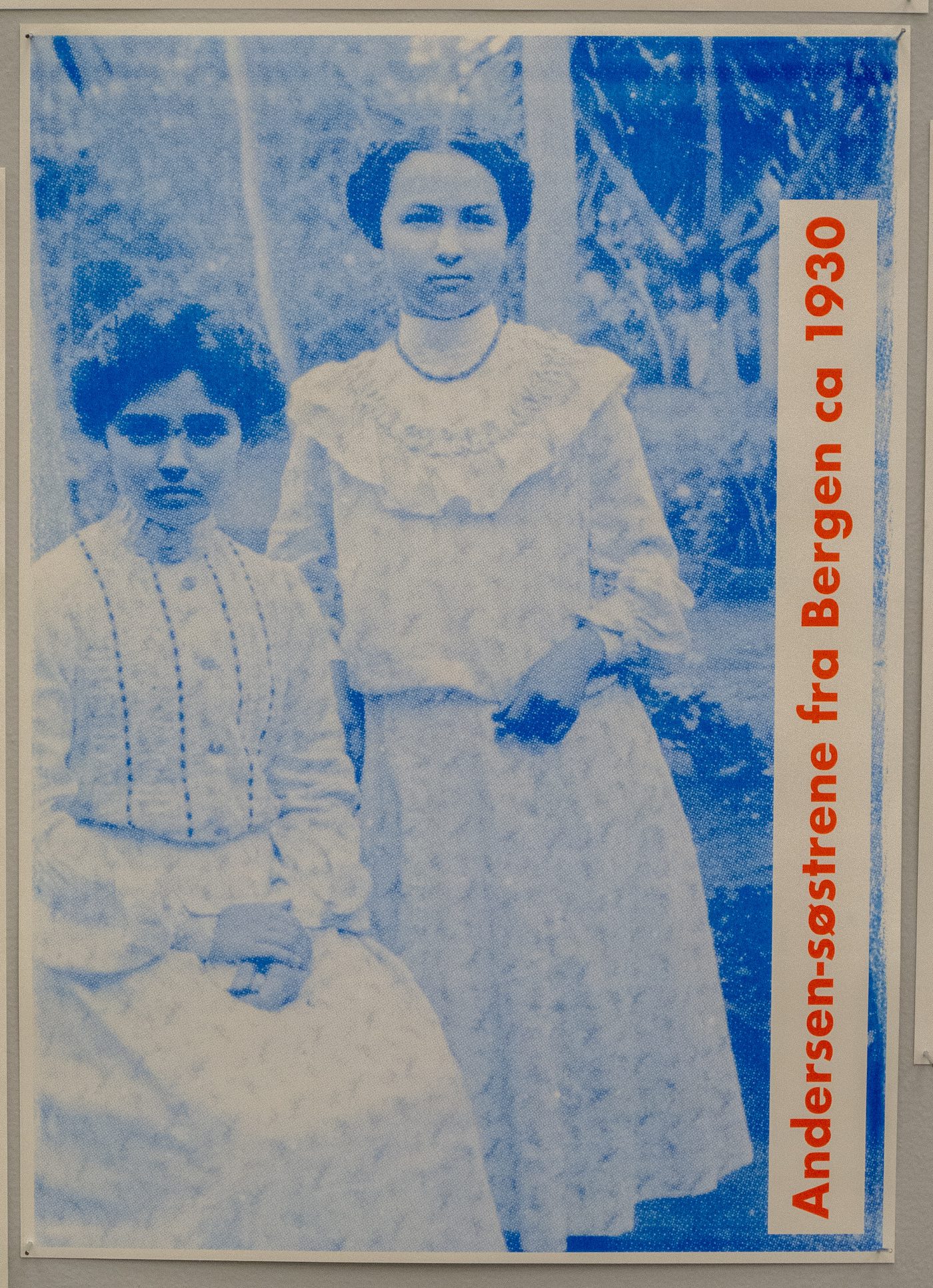

Installation View, Exhibition Bergen Assembly 2019. The creators of Oi! (Arsiema Z. Medhanie, Ayan Mohamed Moalim Abdulle, Cynthia Njoki Kangethe, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, Gift H. Solhaug, Hamisi Adam Moshi, Hinda Sheikh Ibrahim Farah, Malebona Maphutse, Mamadee King Kabba, Naomi Niyo Bazira, Omar Farah, Sheila Feruzi Kassim, Shelmith Mwenesi Øseth, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Sufian Mulumba), Oi!, 2019. Risograph prints on paper, dimensions variable.

In early 2019 fifteen young people of color (including me) started meeting up in Bergen. Every three to four weeks, we would discuss what it means to be a person of color in present-day Norway. For the third triennial arts exhibition Bergen Assembly, artist and scholar Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa had invited us to initiate these discussions while working with Johannsburg-based artists Simnikiwe Buhlungu and Malebona Maphutse on a series of prints for the exhibition. Our print-making group inspired new local initiatives for people of color, started conversations on representation and Black history in Norway, and gained the attention of Arts Council Norway.

Many of the participants had never spoken publicly about the frustrations, stereotyping, prejudice, and acts of exclusion that we face as ethnic minorities in work, school, and other public spaces in Norway. Discussions also centered around the difficulty of embracing an Afro-Norwegian identity in a society that continues to understand “Norwegianess” as synonymous with whiteness.

Installation View, Exhibition Bergen Assembly 2019. The creators of Oi! (Arsiema Z. Medhanie, Ayan Mohamed Moalim Abdulle, Cynthia Njoki Kangethe, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, Gift H. Solhaug, Hamisi Adam Moshi, Hinda Sheikh Ibrahim Farah, Malebona Maphutse, Mamadee King Kabba, Naomi Niyo Bazira, Omar Farah, Sheila Feruzi Kassim, Shelmith Mwenesi Øseth, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Sufian Mulumba), Oi!, 2019. Risograph prints on paper, dimensions variable.

As Yacoubi Cissé and Ann Falahat’s book Afrikanere i Norge gjennom 400år (400 Years of Africans in Norway, 2011) attests, there has been a Black presence in Norway for centuries. According to a census conducted last year, Africans and Norwegians of African origin constitute roughly 14 percent of the 979,254 people whom the state describes as having “immigrant backgrounds.” The number is probably much higher, since the census does not account for people from African Diasporas in the Americas, Europe, or Asia.

When people of color voice their frustrations, we fear being perceived as disturbing the peace due to hidden power structures in Norwegian society. This is partly because the concept of Norwegianess is built on virtues such as solidarity, freedom, peace, and egalitarianism. Former Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland once said: “It is typically Norwegian to be good.” Although this was in reference to the country’s economic and welfare system, it tapped into other associations of Norwegian goodness – from the Nobel Peace Prize to international development to fighting for democracy abroad. Such statements help project Norway as an open and tolerant society, despite evidence to the contrary.

Collective amnesia is needed to maintain this image of goodness. A narrative about Norway’s history of oppression by Sweden and Denmark until 1905 is often used to exempt it from accusations of racism today. Meanwhile, the Norwegian lexicon describes that period of colonial rule as a union, which hints at shared interests. Colonialism is used to minimize Norway’s involvement in the Napoleonic Wars and the transatlantic slave trade, to which it contributed ships, sailors, and soldiers while under Danish rule. There is also denial about the effects of 800,000 Norwegians migrating to the US between 1825 and 1910, adding to the further displacement of Native Americans, which is excused by the emigrants’ poverty. Last but not least is the fact that Norway itself is a settler colony with a history of oppressing the indigenous Sami population in the country’s north.

The visibility of the African Diaspora in Norway has grown in recent years with increased numbers of African refugees. Sadly, intensifying Islamophobia and xenophobia has led to several atrocities committed by Norwegian white supremacists. The first of note was the murder of fifteen-year-old Afro-Norwegian Benjamin Hermansen by three neo-Nazis on January 26, 2001, in Oslo. Benjamin’s death mobilized the country’s first nationwide anti-racism protest. Still, on July 22, 2011, a right-wing terrorist detonated a bomb in Oslo and then killed seventy-seven people and injured 319 at the Norwegian Labour Party’s Youth Camp in Utøya. The killer’s manifesto said his actions were a protest against a “Muslim invasion” of Europe. He had long been a member of the right-wing Progress Party, which seeks to restrict immigration. Two years after the massacre, the party was elected to power. In late 2019, a twenty-one-year-old Norwegian killed his seventeen-year-old stepsister, Johanne Zhangjia Ihle-Hansen, who was of Chinese origins, and then unsuccessfully attempted a mass shooting at the al-Noor mosque just outside Oslo.

These accumulated incidents have a silencing effect, and an implicit expectation for minorities to assimilate. Anthropologist Marianne Gullestad acknowledges this in her book Plausible Prejudice (2006): “Immigrants who do not play down their differences are perceived as provoking hostility, thus threatening the narratives about Norway as a homogenous, tolerant, anti-racist, and peace-loving society.” But how can a Black person play down the color of their skin?

Somali-born Muslim writer and public speaker Sumaya Jirde Ali can attest to the negative experience of provoking the Norwegian public with political opinions. The public shaming she faced was brutal enough for her to withdraw. In an interview on national television (NRK) in 2018, journalist Ole Torp opened by asking her, “Why do you think people are afraid of you?” Ali responded: “I’m viewed as a guest. Guests should be nice and grateful. The tyranny of gratitude oppresses me if I state my opinions. It has become so that I have received some serious threats of being encircled and beaten. There are many who attack my religion and my skin color. They want to bully me into silence.”

Germain Ngoma, Ladle and Runner, 2019. Installation view at Oslo Kunstforening. Photo: Christina Leithe Hansen.

Even positive public recognition can be tokenistic and met with prejudice. This January, after Zimbabwean artist Germain Ngoma won a prestigious scholarship from the Norwegian Bank, a response was published on a new arts website by well-known critic Lars Elton titled, in reference to a brand of whitening powder, “From Blendahvitt to a mix of colours.” According to online magazine Subjekt, the text, now deleted, asserted that Ngoma received the award not based on merit but for his skin color, because over half of the jury was not “ethnic Norwegian.” Yet Ngoma is one of Norway’s leading sculptors, with a career spanning over three decades.

In 2019, Hinda Sheikh Ibrahim Farah, Wolukau-Wanambwa, and I were invited to present the Bergen Assembly print project at a major conference about exclusion in the arts organized by Arts Council Norway, but the whole event was overshadowed by the decision to title one panel “Can Art Make the World Great Again?” – clearly playing on the slogan of US President Donald Trump, whose campaign was built on promises of exclusion and racist rhetoric.

Certain shifts within Norwegian society do suggest an inclination toward more inclusion. The Arts Council has created a one-year fulltime work scheme to increase the number of ethnic minorities working in higher positions in arts and culture. Many Norway-based Black artists, such as Ngoma, Sandra Mujinga, Frida Orupabo, Herman Mbamba, and Annie Anawana Haloba, are gaining international recognition. There are now institutions run by people of color, like the Nordic Black Theatre and Khartoum Contemporary Art Center. Many new groups are addressing the needs of people of color, including Vestland Dansteater and Arise Community. Participants from our print project reestablished the African Student Union in west Norway to continue discussions. Outside of the safe spaces we create for ourselves, however, it remains to be seen if there truly is room for an Afro-Norwegian identity within the greater Norwegian society.

Sheila Feruzi is an Afro-Norwegian screenwriter and film producer currently based in Bergen, Norway. Through the upcoming media company Vuma she is developing podcasts and digital media solutions that will highlight content by multicultural creators in Norway.

THE NORDICS

More Editorial