David Koloane, the South African artist known for his drawings, paintings, and collages exploring questions about political injustice and human rights, passed away in June 2019. His friend and colleague Steven Sack retraces Koloane’s incredible career and life in South Africa.

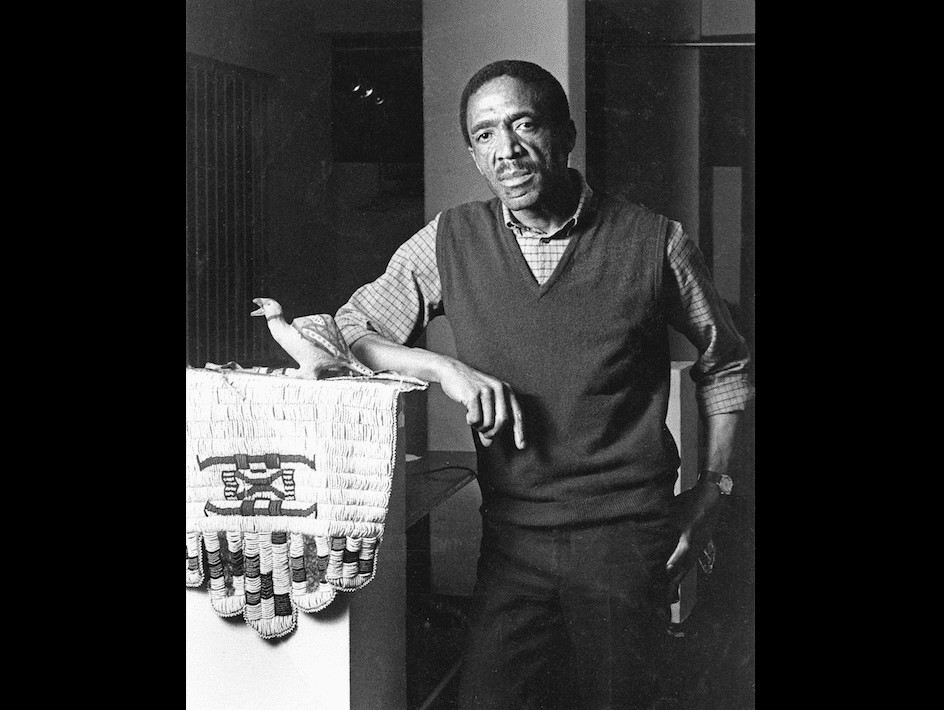

Archival photograph of David Koloane. Courtesy Goodman Gallery

So many have written about and celebrated the life of David Koloane. My small addition is about being in the world and being in the studio.

The realization of the necessity for a social practice of art constituted an historic moment of our generation. We were equally described as activists, cultural workers, and fine artists. The visual arts — fine art, visual culture, political posters, photography, sculpture, graphics, street art, beadwork —made at the time, represented the future in the present… and so it is no surprise that the lives we lived before 1994 were a set of rehearsals, enactments, performances, and failures, in our making of the future to come.

The 1970s and 1980s were turbulent and entangled. It was in this context that the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Johannesburg provided a strong social theory and practice, and an art department that was rigorous – albeit at the time very formalist and Eurocentric in its focus.

But Black students could not gain access to this great institution. The studio of white South African artist Bill Ainslie was the only place to undertake a student apprenticeship. We who were at Wits were privileged and “in the system”, but it gave us both deep anxiety and a fight-or-flight instinct. Bill provided us a way to cross the boundary to the other side – and within a fearful city, to begin to make inclusive spaces of artistic liberation before, and as a rehearsal to, national liberation.

Bill Ainslie knew he had to have other artists – and specifically Black artists – around him, in his home, making art, and conversing about life, in what he called “the cracks of apartheid.”

I cannot separate Bill and David in my memory. While Bill lived his audacious life he had to focus an enormous amount of time on not being in the studio.

Which is why, in my view, he eventually had to hand over the management to a new generation, of which David was a crucial part. Bill had had enough of being “in the world”. His auditions, rehearsals, networking, foraging – his “talking up a storm” – could now end and he would retire to – or be re-invigorated by – his studio.

My most intense association with David was after Bill’s death in the space of the collapsing Johannesburg Art Foundation. We thought we could hold it all together but, with Bill’s passing, the contradictions were too great – his deification became debilitating.

In the early years, David’s quietness was a sign of the times, a brooding manifestation of the silenced Black voice, not meant to be heard. English was the language of discourse at the time. I watched and listened as he found his voice and occupied a physical space that was prescribed by racial spatial planning. David became part of an unfolding, an opening-up, an expansion that contributed to a collective social practice in the arts. He knew that nothing could emerge in isolation – the forces of oppression were too overwhelming. One had to be altruistic, communal, and social – one had to merge one’s ego into a collective quest to maintain one’s humor and enable shared voices and practices to emerge.

Historically, artists’ workshops up to the late 1980s developed along strong stylistic tendencies. Polly Street and Rorkes Drift had distinctive styles. Polly Street ushered in a sculptural and graphic language that evoked early forms of the image of the body associated with older African traditions; Rorkes Drift, on the other hand, invited an engagement with Christian and African spiritualties through graphic black ink prints. The work by these small groups of artists often had a similar appearance because of the limitation on materials; artists mostly worked with a very restricted set of tools.

As they began to access studio spaces and new materials, or materials in greater volumes, new individual styles began to emerge: artists could begin to find their way into being full-time in their studios and finding own styles. David was central to this process and the studios that he helped establish at the Bag Factory in Fordsburg made it possible for artists to access professional studio space and associated resources, such as a gallery and a printmaking studio.

Who were the other art cognoscenti at that time? They came through both absences and presences. Many of them we knew only by name and through glimpses of some of their art. Samuele Makoanyane, Douglas Portway, Dumile Feni, Ernst Mancoba, Arthur Goldreich, Gladys Mgudlandlu, Rebecca Mathibe, Dinah Molefe, John Muafangejo, Cyprian Shilakoe, Andrew Motshoadi, Ephraim Ngatane, and many more. Of that group only Rebecca Mathibe lives on.

We would not have found them in our Johannesburg Art Gallery. We would not learn about them in our academic studies. We would know nothing of their deep African identities, their poetics, their spiritualties, and their depictions of their Africaness. So many of the early generation of artists had no access to schooling or academic training, and yet they claimed and depicted landscape, the human body, and their urban realities, through paint, pencil and watercolour.

It was so-called township art, unconfrontational and often colourful township scenes of “match-box” houses, that were a commercially viable imagery in the White market. (Later David would revisit the township scene – but with a very different, dark and searing eye.) The plastic arts that emerged from Polly Street and the graphics and tapestries from Rorkes Drift would shift the discourse seismically and allow the intangible and the imagined to emerge.

David spent time on the periphery of the Polly Street scene, but his association with it was not as rewarding for him as it was for the sculptors and woodblock engravers who worked there. Painters – David included – were largely to emerge from the Johannesburg Art Foundation rather than from Polly Street.

As I remember David now, I reflect on Bill’s death, which occurred on 29 August 1989, thirty years ago. I can see David and Bill and others, talking about the next milestone in the evolving “artists’ workshops,” and they would have been planning their trip to Zimbabwe, to Cyrene Mission, to participate in the inaugural Pachipamwe workshop. As a young man, Bill had taught at Cyrene Mission and this was a historic return. He would never return to Johannesburg, but die tragically just at the point at which he appeared to have resolved his personal struggle to focus on only making art.

David Kolaoane, equally, understood the need to build institutions; to herald new opportunities for black artists; to be organisers of their own destinies; curators of their community of artists; and writers of their thoughts and processes. But ultimately his main objective was to develop a personal studio practice.

It’s my time to get out of the world and into the studio and to do as Bill and David did and keep making art, in these times that present such challenges to our human condition. It is up to us, artists, curators, patrons, and friends to keep the torch burning.

More Editorial