The Netherlands was one of the most belligerent European colonial empires. Driven by commerce and spread over four continents, their imperial ambitions changed the lives and cultures of millions of people from Indonesia to the Caribbean. In this series we speak to artists and arts practitioners dealing with the legacies of that empire, in the Netherlands and beyond. In this interview C& spoke with artist Remy Jungerman about African heritage, New York, and new artistic centers.

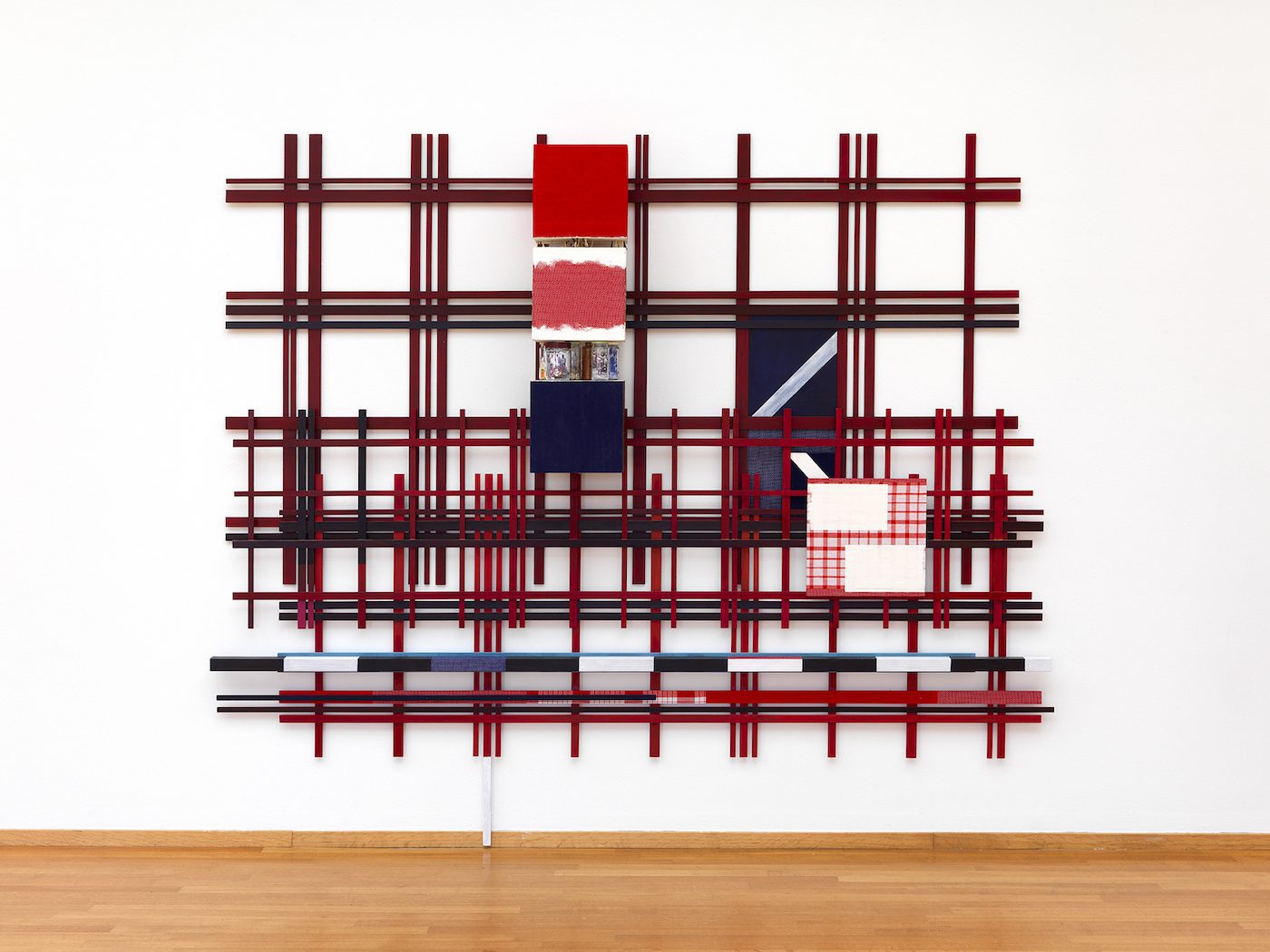

Remy Jungerman, INITIANDS, 205. Painted wood, cotton textile, kaolin, bottles 112 x 96 x 16 inch (284 x 244 x 41 cm) photo© Aatjan Renders. Courtesy the artist

In Remy Jungerman’s work, patterns and motifs from Africa, Maroon culture, and twentieth-century modernism merge with each other. By allowing the influences of different cultural spheres and ages to come together, the Suriname-born Dutch artist creates installations that suggest the condensation of time.

Contemporary And: Your artwork is very much influenced by the Winti religion, the Maroon culture of Suriname, and the De Stijl movement. What is it about these sources of inspiration that interests you, and how do they become visible in your art?

Remy Jungerman: I am fascinated by how dominant Western culture operates and has kept a monopoly on contemporary art, and how art from African perspectives is just read historically in one way. Western culture has traditionally denied the contemporaneity of art from African perspectives and yet enriched itself by using it. So I am interested in creating work from a new center that looks on that scenario from a different perspective and in doing so outs the dominant Western culture.

Remy Jungerman, Horizontal Obeah VODUPAATI, 2017. Cotton textile, kaolin, wood, acrylic and nails 14 × 76 × 4 in. (35.56 × 193.04 × 10.16 cm) photo ©Aatjan Renders. Courtesy the artist.

C&: What do you mean by “creating a new center”?

RJ: All histories are based in different centers. Europe created its own center and of course imposed it on a major part of the world, but other cultures still survived and created their own centers as well. A center is something that enables you to look first at your own cultural heritage and then step back to view the world from a larger perspective.

It is the space in between that interests me the most. When you refer to things, when you turn things back, you enter an open space. My practice isn’t politically influenced, but rather looks on its inner self. So I am interested in work that relates to my own origin and not only to a Western model. I want to see what happens when I leave this constructed Western center, which I am also part of, and go into a space in between.

C&: You draw such a strong line between Western contemporary art and non-Western contemporary art?

RJ: Yes, because the line has always been drawn. I think a Western perspective allows very little space for a non-Western perspective. Maybe this is a bit old-fashioned, but I think this is still a reflex in our society. We, most Black artists in general, have been always part of the Western context, but we still do practice from the margin, from the edges, from the outside. This is where the struggle is, and this is why I am interested in relocating the center and creating work which comes from that base, from the inside.

Exhibition View – IN TRANSIT, 2017 @ Expositieruimte 38 CC – Delft, NL. Photo© Aatjan Renders. Courtesy the artist.

C&: That brings me to your representation of the Netherlands at the Venice Biennale in 2019. Why did you, Iris Kensmil, and the curator, Benno Tempel, decide to make “identity” its theme? Why do you think identity is a topic artists from Africa and the Diaspora across generations are often confronted with?

RJ: Identity topics bring me into a certain conflict, because I am a global citizen. I like to explore things which are related to my culture. And culture is pretty different to identity or Blackness, terms which I do not understand or affirm. I am an artist who comes from a specific background, and I carry a certain knowledge and a certain aesthetics with me. And when my work is only related to identity or Blackness, it can’t be understood in its full complexity.

But I know that we can’t escape from it in a Dutch context. So when Iris, our curator Benno Tempel, and I began to discuss the exhibition, we thought that, in fact, the best way to deal with the inevitable subject of identity was to turn it into a question. By bringing the discussion to a larger audience, by bringing it into consideration. Especially now, at this point in history, when the whole of Europe is under construction again, it is important to look at our shared history.

Remy Jungerman, NKISI PAKAMUTU, 2916. Cotton textile, MDF wood, nails, yarn, kaolin 15,7 x 16,5 x 33,5 inch (40 x 42 x 85 cm) photo© Aatjan renders. Courtesy the artist.

(Nkisi are spirits, or an object that a spirit inhabits. It is frequently applied to a variety of objects used throughout the Congo Basin in Central Africa that are believed to contain spiritual powers or spirits. The term and its concept have passed with the Atlantic slave trade to the Americas.

Pakamutu is a tern used for cleansing ritual in the forrest by the Surinamese Maroons)

C&: You’re currently spending one year at the International Studio and Curatorial Program in New York on a residency funded by the Mondriaan Fund. How is it? And from the vantage point of being in the US, how do you see the far-right movements in Europe and the Netherlands?

RJ: I really like being here. I like the energy of New York, the diversity here, and the enthusiasm of the artist community. I like the fact that there is so much to see. It is giving me a positive energy very different from that I experience in the Netherlands. I am not so much focused on politics. I do not have television, I do not watch the news. So right now I am enjoying a space in which I try to not get overly disturbed by populists and racists, even though I know, sadly, that they are having a big impact on our society. I do not want to let that through into my system, to let it become something which holds me back.

This is also why I do not make it a topic in my art. I chose rather to celebrate African heritage, African aesthetics. I hope by doing this I feed society in a way that helps people look at this heritage beyond just the horror of slavery and colonialism – for example, to see all the great art, culture, and just humanity that has come out of it. Still, as much as I attempt to focus on my work, my career has always been influenced by how political streams go, so now representing the Netherlands in Venice is a big thing. It is a possibility to enter the holy ground of Dutch nationalism and rewrite that history. I want to celebrate that.

Remy Jungerman (1959) was born in Moengo, Suriname and has lived in Amsterdam since 1990. As a sculptor/ mixed media artist his recent work is intrinsically related to his Surinamese origins and is centered on global citizenship in today’s society. Jungerman uses collages, sculptures and installations to show cultural critique(s) of the local and the global, the internal and the external. He first studied art at the Academy for Higher Arts and Cultural Studies, Paramaribo (Suriname). After moving to Amsterdam in 1990 he studied at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy. In 2008 he received the Fritschy Culture Award from the Museum het Domein, Sittard The Netherlands.

Interview by Theresa Sigmund.

More Editorial