.

At 38, sociologist Marielle Franco was an active voice in the defense of Human Rights and the struggle for dignity and respect of minorities. When she was killed, she was fully exercising her first term as Councilor, having been elected with 46 thousand votes. Black, poor, raised in the Maré Favela, one of the most violent slums in Rio, Marielle was a voice who spoke without fear and which, increasingly, was listened to and respected. And she was not afraid to denounce police brutality, to bring them to justice. During her last days alive, she specifically examined the extermination of poor and black youth in Rio’s neighborhoods. “How many more will need to die for this war to end?”, she asked, on social media, days before becoming another victim herself. In whose interest was it to silence this voice? Who else did the shots want to intimidate?

C& América Latina heard what Brazilian artists had to say about what Marielle’s death represents for Afro-Brazilians in terms of curtailment of freedom on the public life of the country.

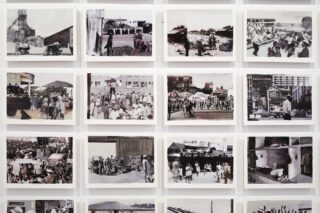

Mídia Ninja, Rio de Janeiro, March 20th 2018. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Renata Felinto: us for ourselves

Curtailment has always been an issue for us. The difference is that now it has become overt that when we, black women, not only thinking, mobilizing and influential, demonstrate that we also have the potential for political conscientiousness, with a wide reach across the national and international community, we took risks that transcend attempts to delegitimize our speech and positions, our conduct and ways of doing politics. Our humanity is delegitimized abruptly and with blood. We have arrived at an extreme point: political groups that find themselves in power (read white male) and who disagreed with the meager gains obtained over the past decades, or even don’t support the multiplicities of thoughts, or even, feel threatened in their hegemonic genocide, decided that not only the voices and the denunciations, the different ideas and perspectives are to be silenced, but also the people, the black women. The setback is thanks to the elites, the political powers, the political parties. With each setback, we will continue moving forward. And, with each Claudia, Luana, Marielle, we will persist, because the struggle is ours to fight. It is clear that no one will do this for us. We’re going to persist in pointing the finger, denouncing, reflecting, questioning. That’s what we have left and nobody can take that away.

Ana Lira: to dilute this culture of sacrifice

If this situation can teach us something, it is to see what we managed to root down. It is to use the networks we have to assert coherent narratives, instead of getting lost in the mishmash of fake news and the pitfalls that redirect the focus. The repercussion of this case and the collective strength it has generated was incredible. There was a great deal of synergy, but I prefer Marielle alive. We cannot die fighting any longer. We need to revisit this trajectory. We can no longer talk about the strength of the black body, if this means more bodies in the indexes of political and media manipulation. We need to dilute this culture of sacrifice, starting with our discourses. I spent the week reflecting on this. Our public life doesn’t manifest only through the political institution, but also in the right to move freely in any sphere. I feel the need to strengthen sustained strategies in order to reaffirm the right to enjoy the full extent of public life, beginning with the smallest daily details. I have adopted certain small habits, like bringing back the sounds of lots of Afro-Brazilian music at home, and very slyly inviting those all around to dance. I’ve done the same with food, clothing, photos, films and texts. Without any hustle and bustle, I keep the debate going through channels that are less obvious. When I think of freedom, I feel that these more silent practices strengthening our public positioning, our collective existence, are effective in supporting other spheres of representation.

Rio de Janeiro. Agência Brasil. Foto: Tânia Rêgo.

Diane Lima: democracy is fiction

Marielle’s execution is a necropolitical monument, which takes shape and forms in our memory, so that we remember the power of institutions like those which boast the right to kill. Symbolically, this death further exposes the fiction our democracy is and alerts us to the paralysis of our bodies: still we march, hands tied, and that is what our gestures reveal. Who do we hope will hear us? Why do we hope for leadership? We are living a period of bankruptcy – political, of the Law and of the social body. In which notion of Justice do we deposit hope, in the one that is murdering us? The words of Margarida Maria Alves, peasant leader from Paraíba, in the Brazilian Northeast, assassinated in 1983 by the latifundia, are illustrative for us as we think through how extermination is practiced today and how horror is established as government practice. She said to us: ‘fear we have, but we don’t use it.’ How many more will have to die for our bodies to be freed of the institutionalized mechanisms of control that keep us in captivity? That is what Marielle and Margarida, who died fighting, asked. And what now more than ever calls upon us to answer.

Jota Mombaça: execution is not the exception, but an effect of the rule

The death of Marielle Franco represents the continuity of the necropolitical regime that organizes black life in Brazil. It is, as Diane Lima wrote, a monument to this regime, and, consequently, it underlines the fact that black people in this country – and perhaps this is true of several other contexts – do not have access to justice, freedom and the right to life, which are formal prerequisites of a society that deems itself democratic. In other words, the death of Marielle reproduces for all black people their captivity, the density of their situation and the brute material of which the society in which we live is made: ordinary violence against black, indigenous and poor people, as well as people deemed sexual dissidents who bring texture to the fictions of security and ontological comfort of those historically privileged by the unequal distribution of this violence. As Cíntia Guedes emphasized, this execution must not be perceived as an exception, but rather as an effect of the social rule that is to exterminate the black population in Brazil – which Marielle died challenging. And, for this reason, her death also represents the continuation of our struggle against the perpetuation of the regime that executed her.

Mídia Ninja, Rio de Janeiro, March 20th 2018. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rosana Paulino: seeds that are uncontrollable and powerful

I believe no one is discussing that the target, Marielle, was handpicked, not only because people were bothered that she was denouncing political violence and pointing the finger at possible suspects. But more than that, people were bothered by the fact that she was a woman who was black, lesbian, and from the slums. Something that is totally unacceptable to the sexist, racist and classist standards of Brazilian society. But instead of confining myself to death, I want to talk about life. Life that burgeons, grows, and bursts open the borders around Maré and become a symbol of struggle seen so rarely in the country. The attempt to curtail, to silence black women is not going to work, as those who carried out this act can see. We will not be intimidated. I boldly use the term “we” which, if it does not include all (unfortunately a significant number of black women are far from this reality), I can say that, for those to whom “the message was given,” it did not go over well. And I am not talking about empty slogans here. For 25 years, I’ve been working on the question of what it is to be black and a woman in Brazil. These past days, I’ve witnessed events I never thought I would see in my life: young black women, some almost girls, leading protests in the streets against barbarism. The bullets that killed Marielle can / may, paradoxically, bring to life the way of doing politics in the country. Like seeds, they are quickly bearing fruit, uncontrollably and powerfully.

Fábia Prates is a journalist whose work has appeared in major Brazilian media outlets. She currently writes on topics related to culture, behavior and corporate communication.

Translated from Portuguese by Sara Hanaburgh.