Rajkamal Kahlon is looking for trouble. At least in the title of her forthcoming exhibition. In "Staying with Trouble" she looks at the history and the imprint of colonialism at the Weltmusem Wien. With C& she talks about translating archival subjects into artistic work and about Black and PoC artists revolting against being assigned the role of ”neoliberal cheerleaders” by certain museums.

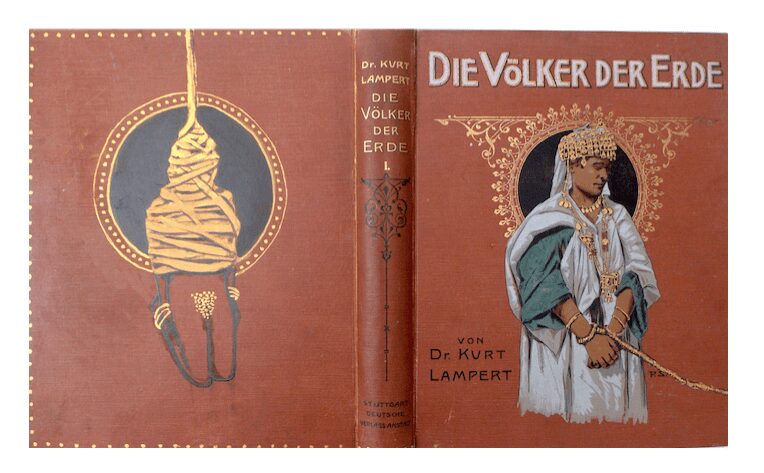

Rajkamal Kahlon. Altered cover of Die Völker Der Erde, by Kurt Lampert, 2017. Ink and gouache on bookcovers. Courtesy the artist.

C&: What is an archive to you?

Rajkamal Kahlon: An archive is about power, representation, and history; it is selective institutional memory. And I’m interested in how history shapes the present, particularly the history of images and the conditions of their production and circulation. I return again and again to the submerged and forgotten histories that are intimately linked to the brutal economic and political systems we are asked to participate in today.

Rajkamal Kahlon, Woman Carrying Limbs, 2017. Ink and Gouache on Watercolor Paper. Courtesy the artist.

C&: In your opinion, what can the artist’s view add to the re-mediation of anthropological collections?

RK: The idea of healing and curing in the Latin sense of the word aligns with my philosophy around art making. Art has deeply spiritual power to heal and transform, although this idea contradicts the contemporary understanding and reality of art as a luxury good. In this context of commodification, artists – and artists of color in particular – are invited into anthropological museums to assume different roles. On the one hand, to be something of a neoliberal cheerleader, adding value to the museum’s brand through our association. On the other, to play the role of native informant and shaman – offering a way to lessen the burden of white institutional guilt.

I had reservations about working with the Weltmuseum Wien for those exact reasons. But my decision to become an artist-in-residence there comes out of the desire for greater access to the objects and vast photographic databases, scientific staff, and other collection caretakers. It took me closer than I had ever been to the heart of the many contradictions and histories of violence embedded in the foundations of this type of museum.

C&: Two main mediums you are working with are drawing and painting. Could you elaborate on your practice of translating archival subjects into artistic work?

RK: As someone who paints, draws and researches archives, I am interested in generating something new, unexpected, and uncanny. After the material is digested over a long period of time and processed, it undergoes a process of visual transformation. By using my own hand in redrawing and repainting the bodies of ethnographic subjects, I’m attempting to rehabilitate those bodies, histories, and cultures that have been erased, distorted, and maligned. I am attempting to give them a new life through embodied acts of recuperation.

Painting also allows me to be at the center of expression, to transmit my experience and my perspective. Painting is how I learned to speak and survive in a world that continually strives to silence my voice and deny my experience. I relate to Carolyn Forché’s idea of a Poetry of Witness which is a poetic response made in the aftermath of a moment of extremity. I am interested in creating a Painting of Witness.

C&: You are also concerned with current politics, as seen in your project Did You Kiss the Dead Body? How is this work connected with your projects related to archives?

RK: This project grew out of an eight-year reflection on autopsy reports emerging from U.S. military prisons in Iraq and Afghanistan, first made public by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 2004. In 2012 I became the first artist-in-residence to work with ACLU’s National Security Project and the human rights attorneys responsible for the release of 100,000 pages of documents related to the Bush-era torture program. The residency was structured around a set of conversations about torture, race, empathy, trauma, truth, justice, and aesthetics. I was interested in augmenting the secular archive with alternate forms of remembrance and mourning in order to help these incarcerations and deaths gain greater significance in our cultural memory.

The residency was a way of exploring the philosophical gap between my view as an artist engaged with ideas of empathy and remembrance and the legal perspective of these documents as rational instruments serving justice. From my standpoint there’s a lot of overlap between an archive of autopsy reports produced by the U.S. military today and a 19th century anthropological archive.

C&: Like most of your works, The ABC’s of Torture and State Violence reflects on various forms of violence. Could you comment on what it is exactly about?

RK: The ABC’s of Torture and State Violence are drawings about state sanctioned violence, made on the pages of an English translation of Carl von Ossietzky’s collected writings, The Stolen Republic. After winning the Nobel Prize, hospitalized and still under surveillance by the National Socialists, Ossietzky had attempted to share his experience of being tortured through a coded request to journalists. He asked if anyone could locate a book for him on medieval torture. I made this set of drawings as my response to his request.

Rajkamal Kahlon, From the Series « Do You Know Our Names, » 2017. Ink and Gouache on Archival Digital Print. Photo credit: Uta Neumann

C&: Could you give us a first insight into your forthcoming exhibition at the Weltmuseum in Vienna?

RK: The exhibition is titled Staying with Trouble, which is also the title of Donna Haraway’s most recent book about how to live and die together in this difficult moment of time. I borrow her idea as a way of thinking through the ethics of working with an ethnographic museum. In many ways the museum can be seen as the instrument of imperial violence par excellence. The seeds of everything we are experiencing today, from a catastrophic environmental collapse and the mass extinction of species to the exponential growth of war-related refugees and the specter of terrorism, can all be found within the walls of the Weltmuseum Wien; in the history of its founding, the context of how its collections came into being, and in the objects, documents, and photographs it houses.

While I was in Vienna to set up the installation for my show, it came to my attention that as part of its grand reopening on October 25th, the Weltmuseum Wien has decided to invite André Heller to host an event. He is the creator of recent neo-colonial spectacles such as Afrika! Afrika!, which continue to be extremely popular in the German-speaking world. While I am not aware of the details behind the decision to invite him, I feel it deeply undermines the politics within which my work is made. It also undermines the work of all the museum’s staff members who have spent years trying to shift the discourse. Instead of signaling the museum as a space of inclusion and rebirth, Heller’s invitation is a clear message that the Weltmuseum Wien, despite its new name and shiny new outfit, continues to be haunted by its colonial ghosts.

The exhibition Staying with Trouble will be on view from 25 October 2017 till 31 March 2018 at the Weltmuseum in Vienna.

From 13 October till 18 November Rajkamal Kahlon’s work is part of the exhibition Precarious Art: Artificial Boundaries at alpha nova & galerie futura, Berlin, Germany. At the opening on 13 October she will be talking about her work.

More Editorial