C& author Andrew Mulenga remembers an artist that has shaped the contemporary Zambian art scene and remains relatively unknown in the West: Henry Tayali. His works are critiques of ‘modernity’ and ‘development’ and tackle topics that are still relevant 30 years after his untimely death.

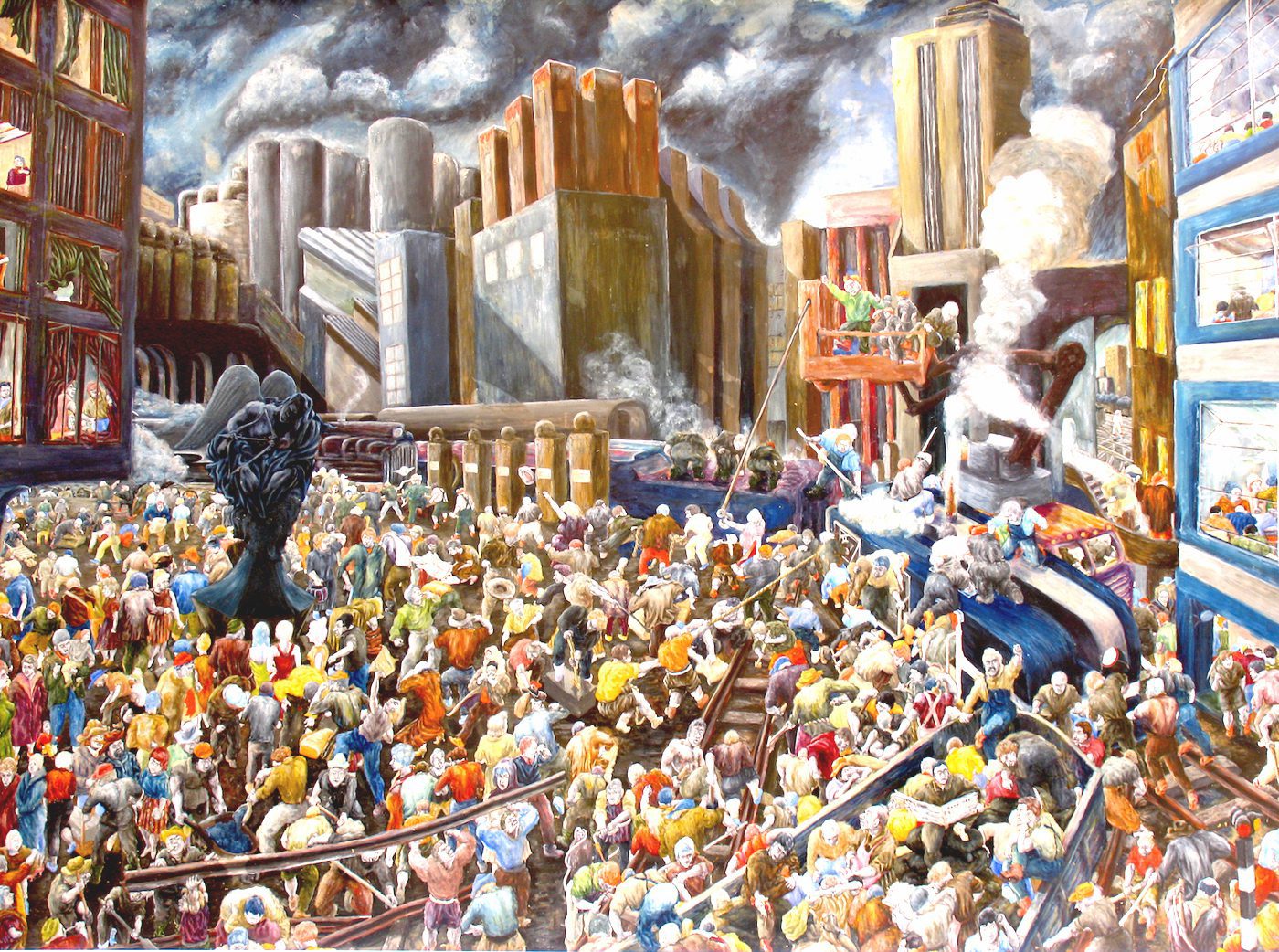

Henry Tayali, Destiny, 1975-80, oil on canvas, 58cm x 89cm. Courtesy of Zukas Family

Industrial structures with massive chimneys puff ominous dark clouds of toxic waste into the sky. To the left and right, the relative comfort of those dwelling in high-rise apartment buildings contrasts with the living standards of the masses below.

A few people among the crowd of factory laborers appear to be misplaced because they are not dressed for manual work: for instance the group of women admiring a sculpture of cupid; or the man in a suit – perhaps a supervisor taking a break – casually reading a newspaper while seated on a heap of rubbish. These are scenes from Henry Tayali’s Destiny (1964-65), one of his earliest and yet most beguiling paintings. Despite having died precisely 30 years ago, no name reigns more supreme in Zambia’s art scene than that of Tayali.

Destiny is set in an industrial dystopia, with the multitude in the foreground mostly working on the construction of a railway line. Rail transport was one of the key instruments during the colonial spread of ‘civilization’ and the transportation of the continent’s natural resources in bulk for Europe’s industrialization.

Taking a closer look at the painting, it seems as if a few members of the elite are mingling with the lower classes. So, is Tayali perhaps referring to the elite’s binary role of socializing and patronizing? At a glance, all his figures appear ethnically ambiguous and there is no telling their race. He created Destiny in his formative years, reflecting the things he used to see around him. Yet his arguments against racial prejudice, injustice, and poverty also found expression in his later works. Tayali responded to contemporary issues that concerned the African liberation, the post-colonial condition, and the welfare of the average person.

When Tayali was still young, his family moved to then Southern Rhodesia, where his talent was noticed by Alex Lambeth, an artist who ran the Mzilikazi Art Centre in Bulawayo. By the time Tayali was ten years old, he had already become a painter of promise. Under the instruction of Lambeth he was introduced to Western academic painting traditions but merely used them in relation to African subjects. In 1958, when Tayali was 15 years old, Lambeth arranged the Bulawayo City Council to sponsor his first solo exhibition, which was also the first ever exhibition put on by an African in Bulawayo.

Tayali won several prizes while still attending high school. But despite the support he received from various people, he was restless and well aware of the unequal opportunities for blacks in Southern Rhodesia, as well as the barriers to his further studies. So he returned to the country that was now independent Zambia and in the process of transformation and nation building.

Settling in Lusaka, he took part in group exhibitions with the Lusaka Art Society (LAS). During this period, the late 1960s, works in the European settler-run LAS predominantly featured evocative landscapes, still lifes, and figurative genres. Tayali’s paintings, however, showed frenzied scenes of African social life in the city and townships, as well as people at bus stops, beer halls, and markets. These abstract representations of crowd scenes, just as the multitudes in Destiny, were political statements. This time the masses represented the silent majority – the electorate.

The time in which the paintings were created marked the beginning of one of the most repressive periods in post-colonial Zambia. The first president, Dr. Kenneth Kaunda, was not taking kindly to any opposition, even from his closest comrades from the liberation. It was a time of tightened national security, as Kaunda had just become the president of the frontline states whose mission was to liberate Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Namibia from white supremacist rule. Commenting on the economic and social challenges of post-colonial nation states was avoided by many intellectuals, artists, and patrons. Not just for safety reasons, but also in order to maintain that the liberation movements were a resounding success. Tayali chose a different approach by using abstraction as a vehicle to expose but veil the concerns of the silent, ‘suppressed majority’.

After his studies at Makerere’s Margaret Trowell School of Arts in Uganda, Tayali returned to Zambia where he held several government posts, including one in the Department of Cultural Services. In 1972 he became a fellow at the German Staatliche Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, where he completed a Master in Fine Arts. He was the first Southern African artist to be awarded a scholarship by the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service).

Back in Zambia, Tayali was involved in seminars, international workshops, and research projects, continually putting forward his ideas of the University of Zambia (UNZA) developing its own school of fine art and suggesting a collection of good quality masks, sculpture, and pottery to be systematically and critically analyzed.

Tayali encouraged the interplay of ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ art, placing emphasis on the necessity of traditional African cultures as a contribution towards modern development in an international dialogue. His many travels abroad, where he vouched for international cultural cooperation, were proof of his conviction. Not least, because he wanted to see art discourse and pedagogy in Zambia advance to international standards.

Henry Tayali, People in the Summer, 1975-80, oil on canvas, 58cm x 89cm. Courtesy of the Zukas family

His ideas were, however, met with opposition, as his fellow scholars, particularly those at UNZA, may not really have acknowledged his perspective or status as a scholar but rather regarded him a ‘mere’ artist. So, until this day, there is no department of fine art at the University of Zambia.

Yet, Tayali’s legacy indicates that Zambia, whose modern and contemporary art scene has been impulsively thriving for just over 50 years, has and is still able to continue producing artist-thinkers, even under disadvantageous conditions. These artists are able to challenge and question the social, historical, aesthetic, and cultural implications of their work and that of others. Tayali’s palette and sense of abstraction with regard to crowd scenes are evident in the works of prominent Zambian artists such as Patrick Mumba, William Miko and Tayali’s protégé, Vincentio Phiri. In fact, the respect that Zambian artists have for him is celebrated in the Henry Tayali Gallery in Lusaka which also houses the Zambia National Visual Arts Council.

It was Okwui Enwezor who remarked that Tayali embodies “the important creative force of African artists, many whom have laboured in obscurity and outside the spotlight, but have nevertheless continued to produce important work.”

Andrew Mulenga is a freelance arts journalist whose main focus is documenting the contemporary art scene of his home country Zambia.

More Editorial