Multimedia artist Phoebe Boswell talks about her latest show, For Every Real Word Spoken, a tribute to the revolutionary power of female collaboration and one further attempt to overcome silence through artistic gesture

Phoebe Boswell, installation view For Every Real Word Spoken. Tiwani Contemporary, London, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary

.

Chiara Cartuccia: Your current show, For Every Real Word Spoken, is a heartfelt tribute to women. To the women in your portraits as well as to all the female figures that have influenced you as an artist and thinker. Can you tell us more about the motivations behind these series of works, and how they configure themselves in the wider framework of your recent practice?

Phoebe Boswell: I have spent the past year engaged in works that explore the politics of the female body. Mutumia is an interactive installation consisting of a looped hand-drawn animation of an army of naked women projected onto the walls of the gallery space, and an interactive floor of hidden sensors, which, when activated by the presence of the audience, enable women’s voices to be heard. Mutumia focused on the notion of protest, on the female body as a site of resistance and power. In later work, FERWS, I am looking more formally at the female form in an art historical context. At how it has been coerced by the male gaze, and how to subvert this, how to make a portrait of a person and give that person the agency she deserves. In the making of both these bodies of work, I’ve asked women to be involved, the work only exists because of their intense involvement. I’ve been overwhelmed by the generosity and openness, the sense of understanding, the necessity of the communications we’ve been having. FERWS really felt to me like an opportunity to breathe all that in and exhale some sort of deep thank you to this sisterhood, this generational, global, rhizomatic conversation that exists between women, which I hadn’t truly felt before embarking on this work.

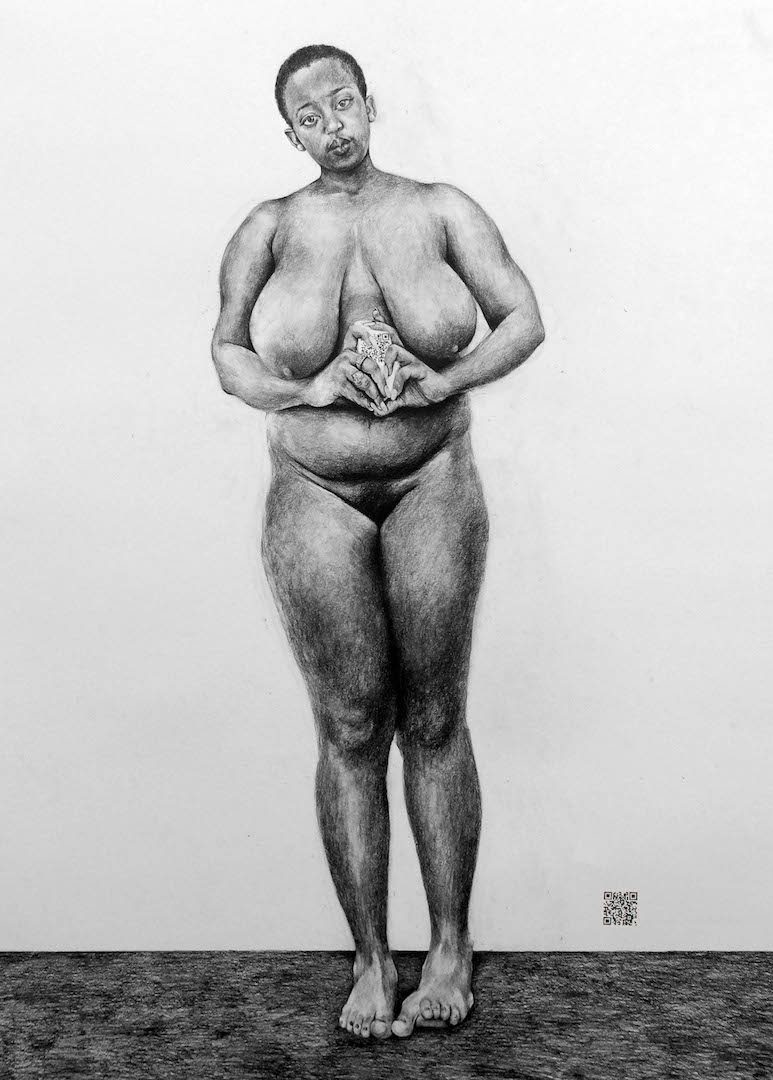

Phoebe Boswell, My Head is Too Small to Contain What I Need to Say, 2017, pencil on paper, 150 x 120cm. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary

CC: The show speaks loudly about the politics of the naked female body, questioning its capacity of being both a bearer of – imposed or otherwise – systems of meanings and a fascinating material object. Yet there is a certain kindness in exposing and (re-)presenting those challenging political issues in your work. How would you comment on that?

PB: For me art making is sort of a therapy, it’s a way of re-examining the stuff that I find difficult, troubling, reprehensible, unconscionable, be it the injustices of history or the inequalities we are still lumbered with today; placing it in the realm of the personal – this vulnerable, intimate space – and dealing with it there, churning it around, battling with it, taking ownership of the narratives in this place which, essentially, must be handled with a gentleness, no matter how violent the content. So when it is transmuted into something tangible to be communicated to an audience, it perhaps retains some of that. It’s empathy really, I guess. Recently I have been thinking a lot about power, and its historic proximity to violence. Wouldn’t it be brilliant to imagine a world where power was closer tied to something that looked more like love? We’re conditioned to think this kind of talk is soft, but I’m saying it here unapologetically and with purpose, as something that can be radical and non-negotiable. I try to administer this throughout my practice.

CC: Your work is often characterised by the use of both traditional and more technologically advanced artistic media. In the case of FEWRS each of the drawings contains a QR Code, which links the images with various material available online, may it be a piece of text, a video, or a song. How did you come up with this idea?

PB: I was mesmerised by this image I found, from Adrian Piper’s Food For The Spirit series, of the artist standing naked, holding her camera up to her chest, gazing out at the viewer, capturing her own image, insisting that this is how she demands to be seen. Food For The Spirit was a project exploring self-care and a decentring of the gaze onto the ‘other’, and it resonated strongly with me while I made Mutumia. I’m intrigued by how we negotiate our identities now, in the age of social media, where we connect and formulate our theoretical selves, practice our identity politics and devise versions of ourselves through which to speak. Asking each of my sitters to think about what it means to project both our theoretical, digital, curated self and our visceral, fleshy, flawed, beautiful, uniquely vulnerable sense was the real impetus of the work, which seeks to reimagine the female nude in art.

Phoebe Boswell, Pieces of a (Wo)man, 2017, pencil on paper, 150 x 120cm. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary

CC: Regarding the rich collection of material included in the show, which is accessible through the QR Codes, I am curious about your process of research in this regard.

PB: Everything you experience via the QR Codes comes directly from the women I drew. It is their communication to you; the drawing just becomes a channel for them to speak through. They also have the agency to change this whenever they choose, for the life of the work. The richness, which you speak of, is a testament to the power in collective women’s voices, which really is what the body of work is about. The title of the show, For Every Real Word Spoken, is taken from Audre Lorde’s Transformation speech, in which she describes the radical self-care gleaned from being in the presence of other women, and insists on the power of our voices. The full title of the speech, delivered in 1980 after she had battled cancer, was The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action, and asked explicitly, “What are the words you do not have yet? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still, in silence?” And she finishes by saying that, although we have been socialised to respect fear more than our own need for language and definition, she chooses to speak out in an attempt to break silence and bridge difference. “For it is not difference that immobilises us, but silence itself.” I hope that, in some way, the proposition offered in For Every Real Word Spoken is, simply, an attempt to break that silence.

Phoebe Boswell recently received the Special Prize by Future Generation Art Prize.

Chiara Cartuccia is an art writer and curator based in London. She is founding co-director of the curatorial platform EX NUNC and PhD candidate at the School for Cultural Analysis, University of Amsterdam.

More Editorial