With Agape Harmani, curator Nicolas Vamvouklis discusses the London-based artist and independent researcher’s latest project, Rizes/Roots/Hundee (2024), developed during a three-month residency at Onassis AiR. Born in Athens to a family of Greeks and Greek Ethiopians, Harmani's work, which often incorporates humor, delves into colonial expressions, ethics, and sustainability.

Nicolas Vamvouklis: Your name carries a beautiful meaning in Greek, signifying love. How would you introduce yourself?

Agape Harmani: Agape means love, it’s my second-first name. My father named me Agape after a girl he met during a Greek summer in the late 1970s. My first-first name is Despina, which means “respectable.” My mother gave me that name after her dear auntie Despina, who passed away fifteen days before I was born. My last name is Harmani, which means blend. So I could probably introduce myself as Respectable Love Blend.

NV: You recently participated in the Onassis AiR, an international artistic research and residency program in Athens. Could you share the highlights of your experience?

AH: Meeting other fellows, gaining inspiration from them, and brainstorming with them led to many new work ideas, some of which I am developing now. I formed real and meaningful relationships and shared experiences with my fellow residents that shaped my practice during the residency, leaving me with threads to untangle moving forward. I felt blessed to have the chance to accept everything the residency offered me.

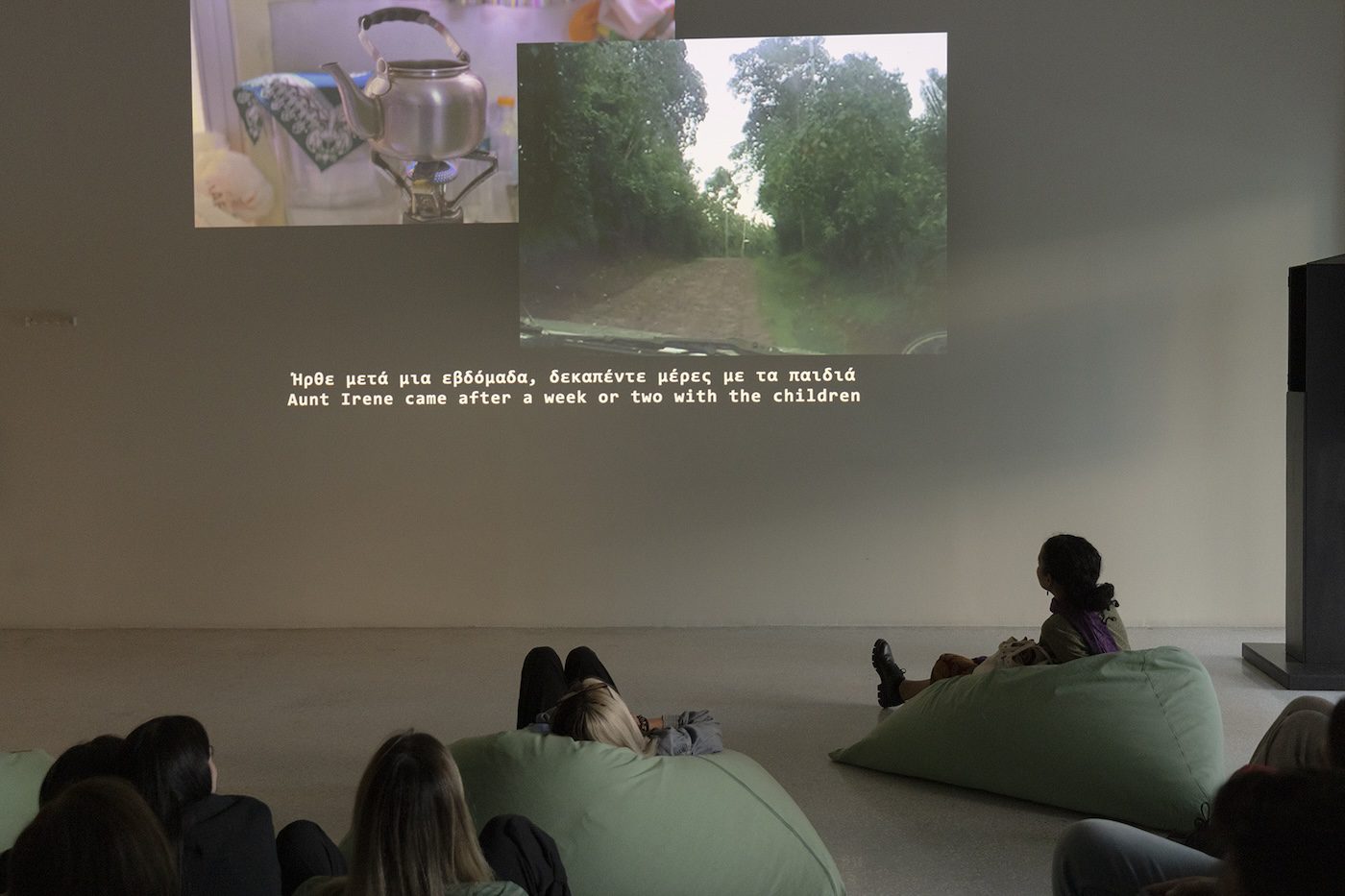

Installation shot of video collage Rizes/Roots/Hundee, 2024, 18’. Photo: Margarita Nikitaki.

NV: Your project during the residency, Rizes/Roots/Hundee (2024), explored migration and identity. Why those themes?

AH: Continuous personal and collective cycles of generational trauma, or history repeating itself. We are the generation that followed a decades-long lifestyle and culture boom that our parents experienced, following their own parents’ war nightmares. And since mental health is a trend in our times, I felt the need to look into my origins to allow for character development – if you’ll allow me to speak in storytelling terms. The research was a part of that exploration, and it allowed me to see my family as adults with their own stories, rather than as “my” dad or “my” aunt. They are part of a life and societal context I have never known and will never know. I don’t even speak one of their mother tongues. I gained more insight into who they are as people.

Many stories were shared with me during this research, and for some reason the ones about identity and migration stayed with me the most. Probably because I found myself in my aunties’ origin stories of childhood and adulting. The content and its reflective quality filled holes in my personal stories and emotions. The process of being a researcher and not my family’s kid was healing. It brought me and my aunties even closer.

NV: When you think of diaspora, what thoughts or emotions come to mind?

AH: Pain. Separation. Anxiety. The traumas and forces that lead someone to migrate. And then the community that follows and the support it provides to individuals.

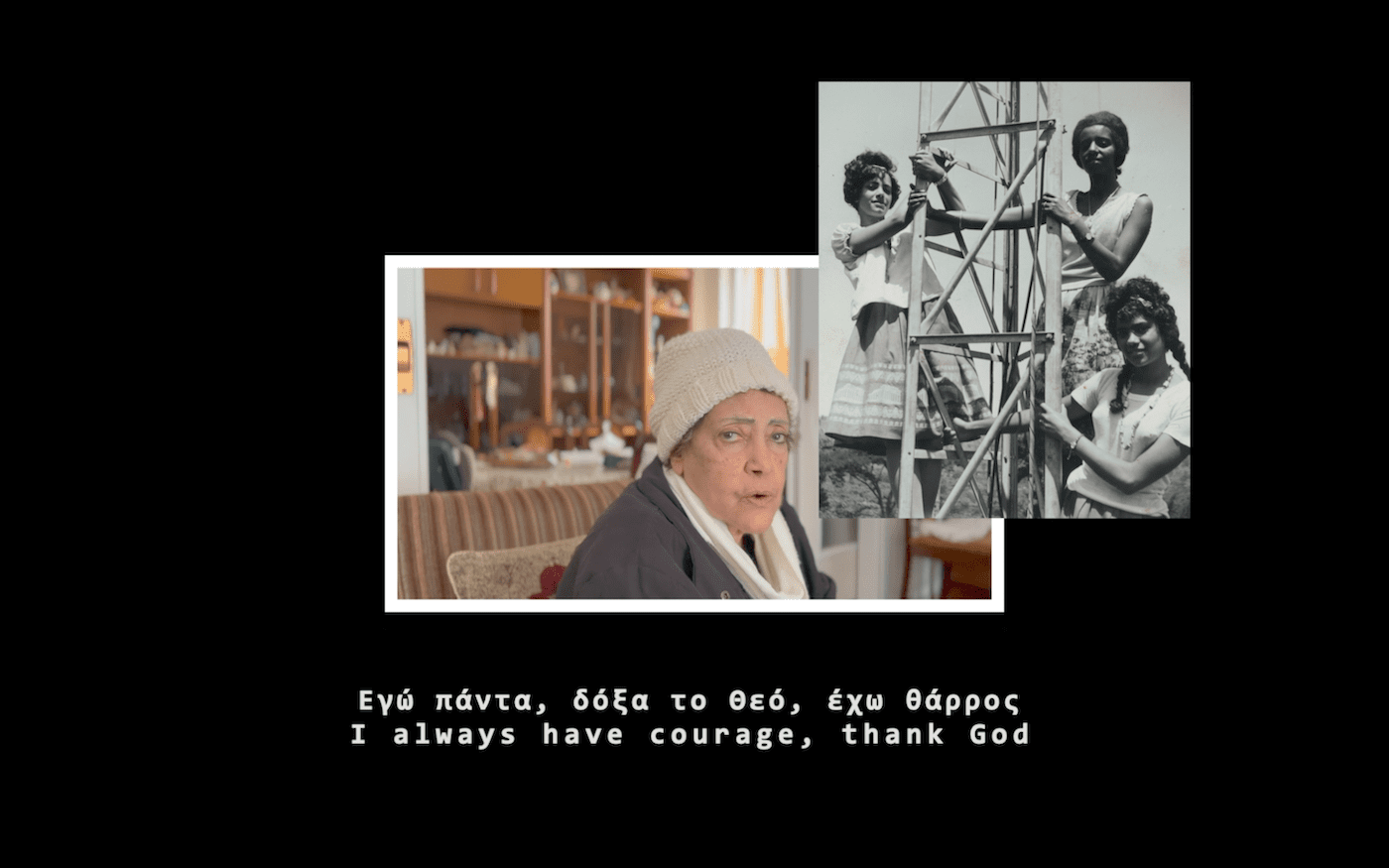

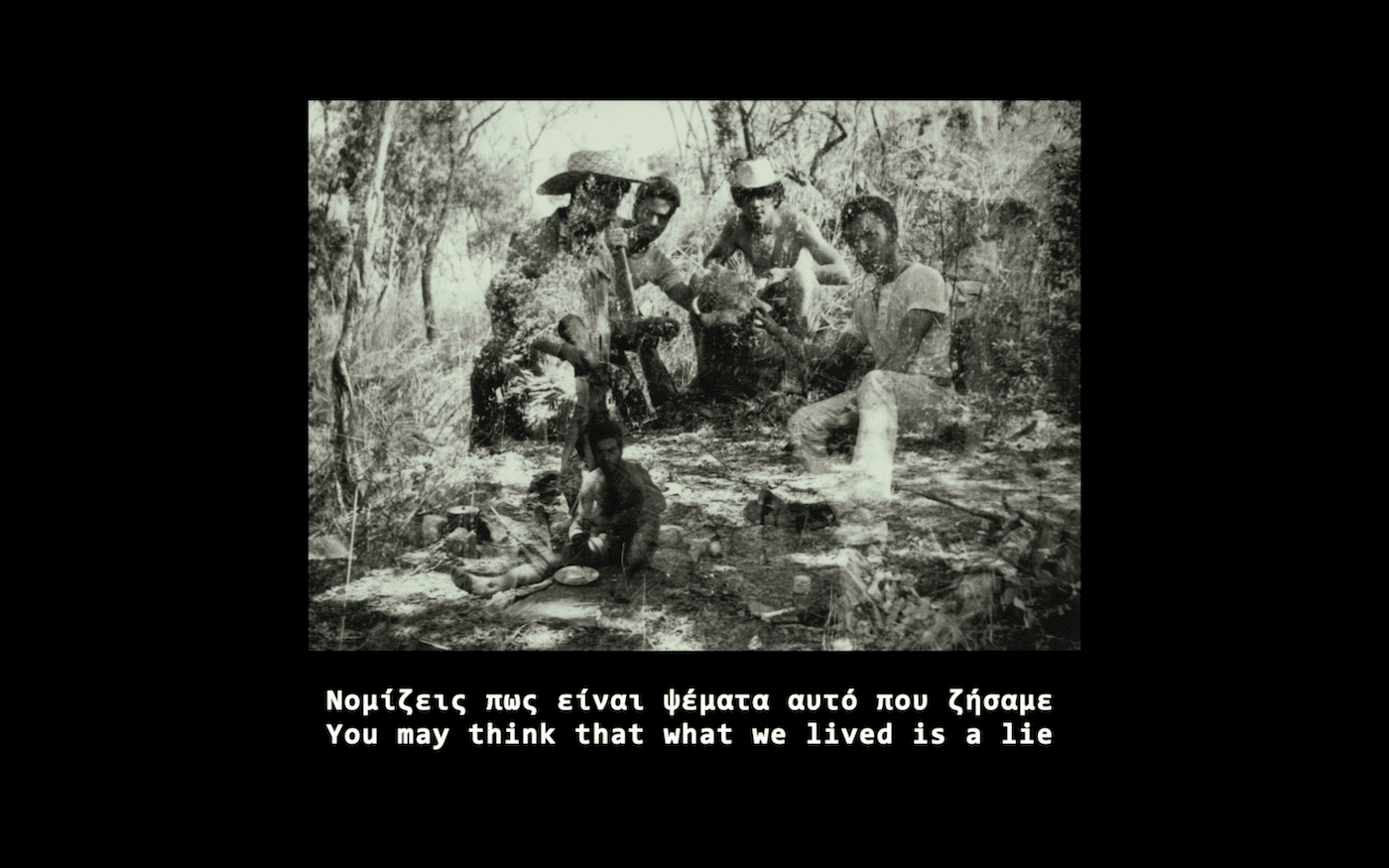

Agape Harmani, Still of Rizes/Roots/Hundee, 2024, video collage, 18’. Courtesy of the artist.

NV: What challenges have you faced in your research, blending personal stories with broader sociopolitical narratives?

AH: The stories that feature “others” are the most challenging yet interesting. The family narrates stories of interaction with Italian occupiers or local tribes in Ethiopia without providing the sociopolitical context that accompanies this past. They talk about the reality of coexisting in a diverse and turbulent context as if it is a collective reality. And in some ways it is a collective reality. When my father’s father was captured by the Italian occupation forces, alongside his father, brothers, and friends in Ethiopia, my mother’s uncle was fighting in the Second World War in Greece. How each family went through war was different, but the feelings of fear and despair were the same. In the case of my father’s father in Ethiopia, the element of race also plays significant part. A mixed-raced, Oromo-Greek man, who spoke fluent Greek, Oromo, and Italian, among other languages, found himself locked in an Italian prison; he found himself out of it again because of his fluent Italian.

NV: During the residency’s open studio day, you presented a series of archival and verbal encounters with your family members. How did they react seeing themselves in the work?

AH: One of my aunties said “we’ll speak about this later,” but we never did. The “parent-child” dynamic resurfaced in the equation. My other auntie now shares stories with me more often than before.

NV: Do you envision an impact for your project in terms of raising awareness about cross-cultural understanding?

AH: There is a very simple yet socially lost notion of collectiveness. People anywhere in the world have the same problems and instincts. Choosing love over fear and vice versa, as a conscious act. Culture wars exist because fear is the default choice in relating to people around us. Fear that’s built up through lack of education and experiences, and due to the national, hetero, and/or financial hegemonies of our society. There is power in relating to the stories of people who look nothing like you but feel things like you do.

NV: Your social media presence often merges reality and fiction. How do you balance those elements, and what do you hope viewers take away?

AH: I don’t hope that balance is maintained. Finding my social media persona to be more honest was a turning point for me. Real-life social presence requires much more effort than video performance. And many viewers relate to the childhood experience of acting or dancing in your room alone – you can be freer when no one is watching.

Screenshot of Η ΚΑΛΗΜΕΡΑ ΤΗΣ ΜΑΡΜΟΤΑΣ (Groundhog Good Day).

NV: I really enjoy your humorous performances on YouTube. Can you elaborate on the role of humor in your practice, particularly in addressing societal norms?

AH: Reality is raging to the extent that it cannot be challenged with rage. Humor is the water to reality’s fire. It’s a way to fight reality without getting more hurt. Performing humor is healing for me.

NV: What plans do you have next?

AH: I’m back in London working and continuing my studio practice. New episodes of my collective YouTube morning show, Η ΚΑΛΗΜΕΡΑ ΤΗΣ ΜΑΡΜΟΤΑΣ (Groundhog Good Day), are coming soon.

Agape Harmani was born in Athens, Greece, to a family of Greeks and Greek Ethiopians. Based in London, she is an independent researcher and artist. Her research explores themes of colonial expressions, ethics, and sustainability. Through her practice, she repurposes waste as an alternative to consumerism, while her performances challenge societal norms and explore identity. Her videos capture fragments of reality and fiction. She holds a BA in Theory and History of Art and an MA in Museums and Galleries, and has worked in galleries and institutions in Athens and London.

@agapyh

Nicolas Vamvouklis is a Greek curator and writer. He is the founder of K-Gold Temporary Gallery in Lesvos and serves as the associate director of The Breeder in Athens.

@vamvouklisn

OVER THE RADAR

More Editorial