Our author Magnus Rosengarten caught up with US artist Lavender Wolf about comics, identity and the richness of the Black Diasporic Archive

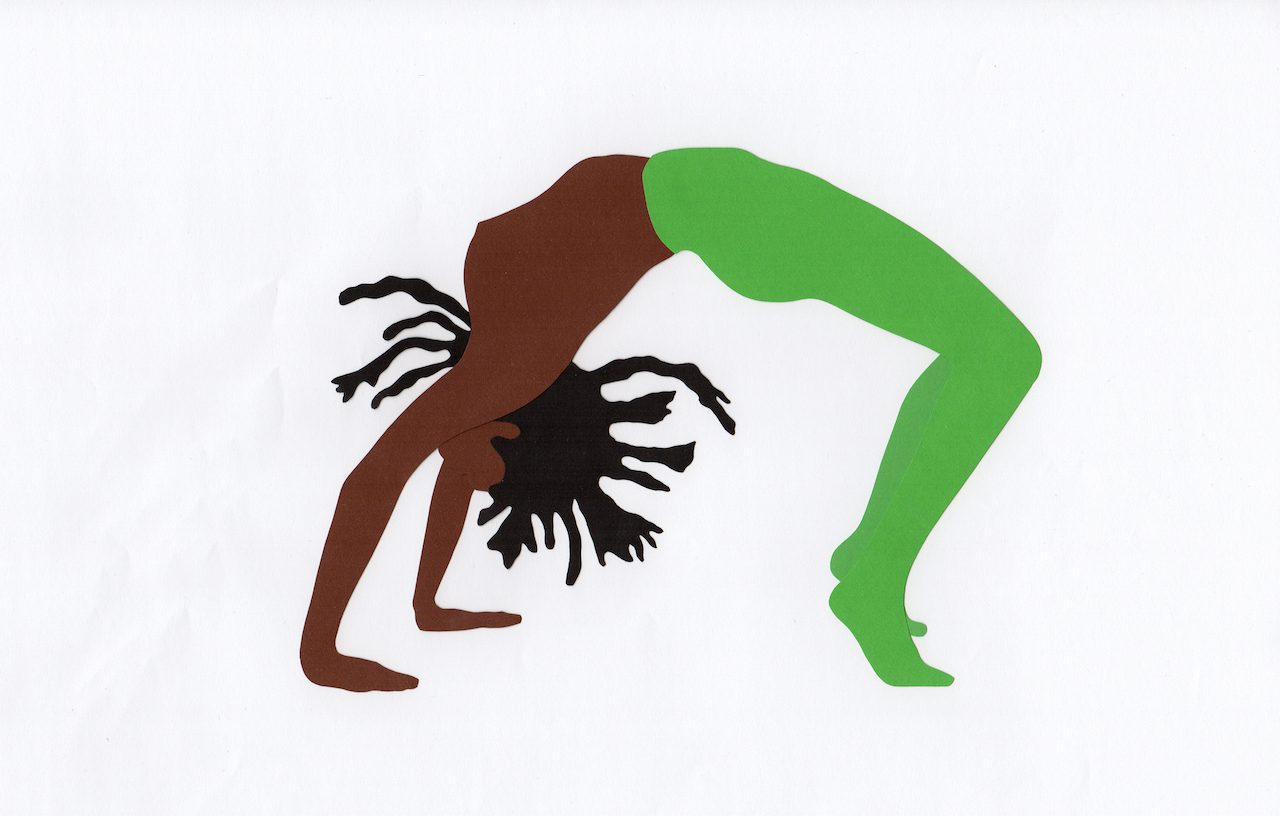

Lavender Wolf, Haven't I Always Bent over Backwards for You, 2016. Drawing. © Lavender Wolf

From comic characters to movie protagonists, SuperQueeroes – Our LGBTI* Heroes and Heroines at Schwules Museum in Berlin took a walk through the history of queer comics. US artist Lavender Wolf was one of the featured artists.

.

Magnus Rosengarten: How do you define a hero?

Lavender Wolf: I think a hero is a complicated person. I was born in 1979 and some of my first heroes would have been He-Man, G.I. Joe, Transformers, and Jesus, because I was growing up in a very Christian family. The idea of a hero was that they were always right. I had this very naive idea of good and evil back then. When I became a teenager, antiheroes became a part of independent culture and I would watch videos like “The Doom Generation” or “The Craft”. Those heroes had altruistic motives, but they were also very complex figures. They would be willing to kill or injure someone.

MR: A selection of your work were recently shown at Schwules Museum* in Berlin (museum for LGBTIQ history and culture). Do you have a conscious queer approach to your work?

LW: The exhibition came to me, actually. I was making these Black Superheroes, taking Wonder Woman, Supergirl or Superman and making them Black. I wanted to put a signature on these very public, powerful pop cultural icons. Basically turning them into figures I myself could relate to. And a lot of people responded to that.

.

MR: What sparked your interest in superheroes?

LW: It came to me in the context of being an American. And it started with Superman, who is thought of as this boy scout character, who is very clean-cut with clear morals. Making him Black just seemed to add more complexity to the story. I also created these “What if?–comics, that ask specific questions: What if Superman was found and raised by Batman’s family, witnessing his parents getting killed? What if Superman was found by the Russian government and then raised in the USSR? What if Superman was Black and raised by a Black family in America? Or: What if Superman was Black and raised by a white family? Would he still relate to his alienness and that total different kind of otherness? Could that be a metaphor for being Black? Would he just become a hero to save Black people? Would he steal power from the government or state? I think these kinds of questions were in the back of my mind, and came to the forefront as I began to develop these superheroes.

MR: You worked with cut-outs and collages for your exhibit in Berlin. What inspired you to use this technique and the different motives?

LW: I am using these magazine cut-outs, figures that have Black faces that I found in magazines or on blogs, and calling them “Transformers”. I am also using car and motorcycle parts to put these characters together in a traditional collage configuration. I initially wanted to make lots of other superheroes but then I became really interested in the idea of the transformers. To me, they are a nod to my childhood, to figures like Optimus Prime. But they also explore a certain fear or prediction that I have of the future. Resources will become scarce, so, how will we use these objects? Will sports cars have a different value? Will they be repurposed for different things?

These transformers, for me, exist in a future where spirit energies and deities that are common in different African cultures take on life and bodies. They take over machines and they form their own societies, their own bodies, genders and sexualities.

MR: What specific cultures are you referring to?

LW: Right now I am researching my own family’s relationship to Hoodoo and Voodoo, so my transformers could be related to West African deities. But that is not so important to me: I have grown up in the US and my family was transported to the country as part of the Atlantic slave trade. There is so much that is lost to me, and I like to work with that idea.

MR: The Schwules Museum is a pretty white institution that is only now beginning to question its own racisms. How can your work be contextualized within this white German gay/queer framework?

LW: I always wanted to go to such a museum as a Black artist and talk about my work. For me it was the opportunity to have a voice. So often, Black bodies are absent from gay/queer discourses and art spaces. There is rarely a three-dimensional perspective on Black people that belong to the LGBTI-Community.

.

.

MR: You’ve been here for nine years. Can you talk about your personal experience as a Black gay man from the States in Berlin?

LW: For almost six years I worked at Rosi’s (famous gay bar in the Kreuzberg district) where I had a DJ residency. I experienced a lot of racism but there is no space to really talk about it except on Facebook and amongst friends. When I have confronted people about the racist comments they’ve made, it’s been dismissed. But I’ve experienced all kinds of things, from people walking up to me asking for drugs, asking how much it would cost to take me home with them, to being called the N-word.

MR: We really need an extensive discussion about these things. But coming back to your artistic approach: How do you personally relate to the vast and rich archive of the Global African Diaspora, how does it inspire you as an artist and as a person?

LW: I watch a lot of videos for inspiration. One of them was the project “I, Too, Am Harvard”, where people talked about things that were said to them. In the beginning of the documentary, one man says that Blackness to him is faith. It is faith in what you don’t see, because often as a people we don’t see ourselves. We don’t see ourselves validated. Another man in the film says that as a Black person, you have to ask questions because things are always presented to you as a given. I feel, as a Black American person, so much of my African heritage has been withheld from me. But I also believe in what many spiritual traditions speak of, this idea of collective knowledge being passed through the genes. I like the idea that the figures I am making come from an intuitive place and that they are their own characters. I am very interested in this future world where things will be repurposed and reused, because we can’t continue to consume things the way we do. It is not sustainable for the planet, the species, and humanity.

.

Magnus Rosengarten is a filmmaker, journalist and writer from Germany. He lives in New York City and currently works towards his M.A. in Performance Studies at NYU.

More Editorial