Mobility in the arts, geographical or otherwise, is often seen as almost a requirement. However, COVID-19 has put to the test this very idea and aspiration. In the series "States of Mobility" we have selected texts that probe assumptions of movement in relation to people on the African continent and beyond. In 2015 we talked to Nigerian curator Bisi Silva, who passed away in 2019 about her role as artistic director of the Bamako Encounters, the importance of Mali as a host country, as well as the importance of the biennale form for African artists.

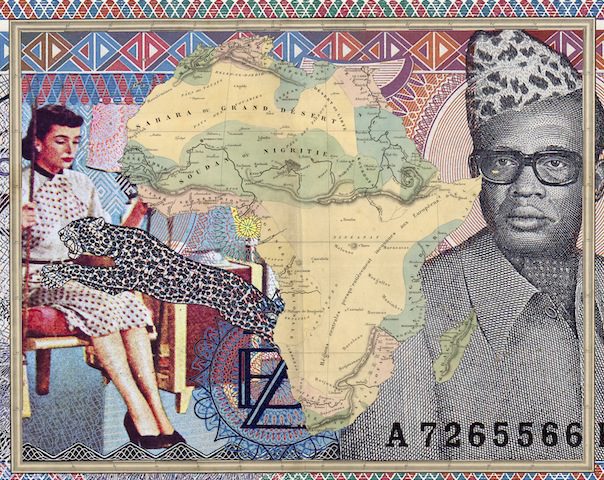

Malala Andrialavidrazana, Figures 1838, Atlas Elementaire, 2015. Courtesy Rencontres de Bamako

C&: As the artistic director of this year’s Bamako Encounters, what do you see as the biennale’s opportunities and challenges, especially given the situation in Mali in the aftermath of the political crisis?

Bisi Silva: I think the cultural sector’s morale needs to be lifted after the unfortunate political insurgency of 2012. The ensuing destabilization affected businesses and resulted in the cancellation of events including the Bamako Encounters. It was a precarious moment and this was palpable within the country. That is what creates a challenging situation. What is reassuring, however, is that there is a collective desire to work towards bringing the country back to a state of normalcy, and the Malian government seems to have understood that culture has to play a big role. The government has understood that it is important to restore local, continental, and international confidence. To stop is to go home, lock the doors, and live in fear. And in such a challenging situation new opportunities open up, that needs people to think, see and act differently and for me that involves creating an international program that is local. Every single Malian photographer has a responsibility to become invested in the Biennale and to believe in the ownership of the event. It has been an educational experience developing an ongoing dialogue with the different photography associations that work in Bamako, but also across the country, and to learn about the ways in which they will bring the Biennale alive and into being. This is the beginning of a new relationship that will extend over and beyond a fixed time.

C&: There have been other biennales such as in Johannesburg or Benin that were unable to continue for different reasons. As an artistic concept, are biennales an important cultural catalyst for African cities?

BS: Yes, I believe they are important because of the lack of infrastructure around the continent, the lack of mobility across it, and the high cost of travel. For me to go from Lagos to Bamako costs nearly 1000 USD. It’s almost cheaper to take a 13-hour flight to New York. The biennales are an opportunity for artists on the continent and in the Diaspora to engage with each other, but also with the rest of the world. It is important that there are platforms big and small for African artists to be able to meet an Ivorian, a Togolese, a Nigerian, a Ugandan, and that this takes place not in Paris or New York, but across the continent. Through such meetings, dialogues and collaborations, more activities can be developed at local level.

C&: Nowadays, young artists from African cities no longer dream of going to Europe and exhibiting in London or Amsterdam. They want to focus on the local power of building artistic infrastructures.

BS: Yes, to a large extent that is true. The idea is not to exclude going to Europe but it should not be the only objective. What is important is that there is a space created within Africa that allows artists to interact professionally. There are many formal and informal collectives working together right now. In Nigeria, for example, Uche Okpa-Iroha has started the Nlele Institute, which is training photographers. They are now doing projects with the Video Art Network of Lagos (VAN), which was founded by Jude Anogwih, Emeka Ogboh and Oyinda Fakeye. Every two months they host what they call a “photo party” where they show slide and video projections and give talks, but also have drinks till the late hours of the night. We need to create more togetherness because that is what makes us stronger and relevant. We will get to a stage where an organization in Lagos or Nairobi will collaborate with the Market Photo Workshop in South Africa and they will meet not outside the continent, but in Bamako. Platforms such as the Bamako Encounters can help to make that happen. Uche Okpa-Iroha called me up recently because they are going to be taking some of their students to Bamako. Today there are funds such as Art Moves Africa or the Prince Claus Ticket fund that enable artists to travel within the continent instead of outside it. A decade ago it seems people had no choice but to make their way to Paris or London.

C&: When you started the Center for Contemporary Art, Lagos (CCA) in 2007, what was your driving force or your vision?

BS: At the time I started CCA, there was no real space for artists working in experimental ways. The Lagos art scene was predominantly commercial, with galleries selling the same kind of work – mainly painting and sculpture with nothing in between. As a curator of contemporary art, I felt that there was no platform to nurture the kind of work I wanted to do. There were few platforms for critical discussion, for developing curatorial practice, or for thinking through ideas and themes. My initial plan was just to start a research/resource center. But then there were some exhibition ideas that I had – for example Like A Virgin (2009) with South African artist and activist Zanele Muholi and Nigerian artist Lucy Azubuike, and I just couldn’t find a space that would take such a provocative exhibition. Finally a friend advised me, “Bisi, if you want to do this thing, just try and open up your own space.” This led to setting up the library as well as an exhibition/workshop space.

C&: After living in France and the UK for over two decades, you relocated to Lagos in 2002. How did you experience this move in terms of your curatorial practice?

BS: I remember that at the beginning I used to call what I do “developmental curating.” Not so much in terms of the traditional use of the word development, but in terms of the fact that there was very little curatorial practice in Nigeria and this had to be developed. Most artists here organize their own or each other’s exhibitions. So for many artists it was their first time working with a curator. I tried to be sensitive to local needs by not trying to “import” ways of doing from Europe or saying “This is how it’s done.” Before I started working as a curator in Nigeria, I spent the first three or four years just going to exhibitions, talking to people, reading, listening and learning. I like to think that my practice is of here and from here, but can also be accessed internationally. But what is important with what I do is to find ways to think about developing a discourse that emanates from the local. Art from across Africa has suffered from a disconnect in terms of the way it is presented, articulated and documented. This has rendered the specificities of local practice and discourse somewhat Diasporic, atemporal, and homogenizing in a way that exists in few other parts of the world.

C&: Your team at this Biennale also includes Issa Diabaté.

BS: Yes, apart from my two dynamic associate curators Yves Chatap and Antawan Byrd, I

am pleased to be working with leading Ivorian architect Issa Diabaté of the Koffi & Diabaté Group in Abidjan. Diabaté will be focusing on the biennale’s exhibition design. I first came across his work when he won the design award at the 1998 edition of Dak’art in Senegal. He also had an exhibition in the OFF program in 2004. Since then I have tried to keep in touch with his work, most recently in Dakar OFF in 2014. There are some great architects working across the continent and we need

to collaborate more with them. Issa Diabaté is only an hour-and-a-half plane trip away from Bamako, so I didn’t feel the need the look to Europe – as is often the case – when we have incredible talent right on our doorstep. His local knowledge is extremely beneficial and pertinent. I believe that as a graduate of the Yale School of Architecture and a keen traveller he will draw from an expanded worldview and then synergize it with his deep local knowledge to produce some interesting results. This fits perfectly with our curatorial and research interests and the questions we are asking, such as « What do we need to put in place in order to engage the local? » or « How does an international biennale have local resonance? » The Bamako Encounters is an appropriate platform from which all of us can explore the possibilities through both small and large gestures.

C&: The Biennale’s title “Telling Time” can also mean speaking or narrating time. What does the title mean to you?

BS: There are countries that I am always fascinated with, India, for example, or Brazil with its history that connects so intricately with mine. Within Africa, it is Mali with its extremely rich material and visual culture as well as a fascinating history and legends – of Timbuktu, of the founder of the Malian Empire, Sundiata Keïta, and of the Mansa Moussa and his trip to Mecca – going back thousands of years. Mali is famous for its griots, for its art of telling stories, of preserving the history of the country, of families, and of individuals through an oral tradition. This notion of telling is a gerund: it’s not “tell,” it’s telling, because it’s continuous from the past to the present and into the future. At the same time, since I started thinking about the Biennale’s title I was relating it to events happening in West Africa. The devastating Ebola epidemic that was ravaging Liberia and Sierra Leone. The uprising in Burkina Faso, the Boko Haram situation in the northern part of Nigeria. I wanted to reflect on what it meant to live today. So I thought that “Telling Time” was really a perfect way to begin to articulate different levels of stories, of narratives. In addition, this edition is a landmark juncture for the Bamako Encounters and it is a moment to reflect on its role in the development of photographic practice from Africa. And I think it is extremely important to ask: Where was African photography when it started and where is it now? And where will it be twenty years from now? It is also important to begin to think of its sustainability: How do we make sure that we safeguard the existence of the biennale? How do we reinvent it so that it becomes and remains relevant to the 21st century? And how can we increase local participation and ownership as part of the future plans? I want people to begin to think about that. The Encounters comes out of the documentary photograph tradition, and since 1994 the work of photographers from Africa has changed and become more diverse. I wanted to highlight these changes. I wanted to open it up to more experimentation, to show that African photography is becoming self-confident, that it is beginning to mature.

C&: Important photographers such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé from Mali or the Nigerian J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, with whom you’ve worked closely, have influenced so many generations of photographers…

BS: Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé are household names in Mali, as Ojeikere is in Nigeria. Younger artists are now looking on the Internet because if you are isolated, if you are based in Luanda or Kigali or Bujumbura, photographers are not passing through on a regular basis. So they are discovering these photographers online and realizing that they were already doing fascinating work three generations ago. Now it is the younger generation’s turn to reinterpret what their predecessors did in the mid–twentieth century and to create something new for the twenty-first.

Bisi Silva ( 1962-2019) was an independent curator and the founder/director of Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (CCA,Lagos) which opened in December 2007. She was co-curator of ‘The Progress of Love’, a transcontinental collaboration across three venues in US and Nigeria (Oct. 2012 – Jan. 2013), of J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere: Moments of Beauty’, Kiasma, Helsinki (April – Nov. 2011) and the 2nd Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, Greece, ‘Praxis: Art in Times of Uncertainty’ in September 2009. In 2006 Silva was one of the curators for the Dakar Biennale in Senegal.

Interview by Julia Grosse.

More Editorial