How a Belgium museum director misread Édouard Glissant, made up a ficticious exhibition title and included the idea of Europe’s “creolisation” in his highly interesting show.

Installation view, Atopolis, Mons 2015. Meschac Gaba, Glo-Balloon (2013) (detail), Photo: Kristien Daem.

The exhibition Atopolis in Mons, Belgium, was born out of a twisted memory, which makes it all the more sympathetic. Dirk Snauwaert, the director of the Brussels museum WIELS, curated the show together with Charlotte Friling and thought he had read the word “atopolis” in a book by the Martinican cultural theorist Édouard Glissant. The mistake became an exhibition title, a contraction between atopos and polis, a non-place and a city. As such, the exhibition Atopolis refers to nothing less than Utopia. But aren’t we, those born in the 20th century, inclined to shiver when we hear that word? We live in a time, in which “everyone is rejecting the new in different ways”, art critic Jonathan Jones recently stated in The Guardian. Does that suggest that an exhibition like Atopolis is out of tune with our times, or may it mark a hopeful change?

I think Atopolis gives us reasons to be optimistic. Snauwaert might have misremembered Édouard Glissant but that didn’t keep the curators from including him into the theoretical backbone of the exhibition. Glissant is male, indeed, but not white, and isn’t that refreshing in a contemporary art world that lives from quoting Foucault, Adorno and Baudrillard? In the context of Mons, the 2015 European Capital of Culture, Glissant’s thinking is inspiring – a thinking that takes the archipelago-like reality of the Caribbean as a model. Glissant’s “creolisation” of Europe involves an ongoing exchange or hybridisation, while simultaneously accepting the irreducible difference – that he calls “opacity” – of each given culture. In Atopolis, Glissant’s “pensée archipélique” is key to Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Globalization Reversed”, a monumental styrofoam workshop space, and Jack Whitten’s black silvery painting “Atopolis: For Édouard Glissant”.

Installation view, Atopolis, Mons 2015. Francis Alÿs, Don’t Cross the Bridge Before You Get to the River (2008), Photo: Kristien Daem.

But the tribute to Glissant also defines the exhibition in more subtly ways. Its set-up is like an archipelago that has no periphery nor a center, with no main entrance or a specific track that you have to follow along. This might be due to the complicated space, a refurbished Civil Guard barrack and an old convent-school, but the limitations were definitely turned into an opportunity. Also, the flyer that accompanies the exhibition doesn’t reveal the nationalities of the twenty-three participating artists. I’m guessing this is a conscious choice, for the exhibition tackles themes of circulation and dislocation with pieces like Meschac Gaba’s Glo-Balloon that condenses national flags on a globe. Gaba’s “balloon” reveals the playfulness of both the artistic and the curatorial approach that can be found throughout the whole exhibition, even when taking on heavy topics such as refugee boats (Francis Alÿs). This playfulness doesn’t annihilate the importance of the issues, but it introduces a certain lightness of being, and evokes, similar to laughter, a moment of rebellion, and in this sense, a way out.

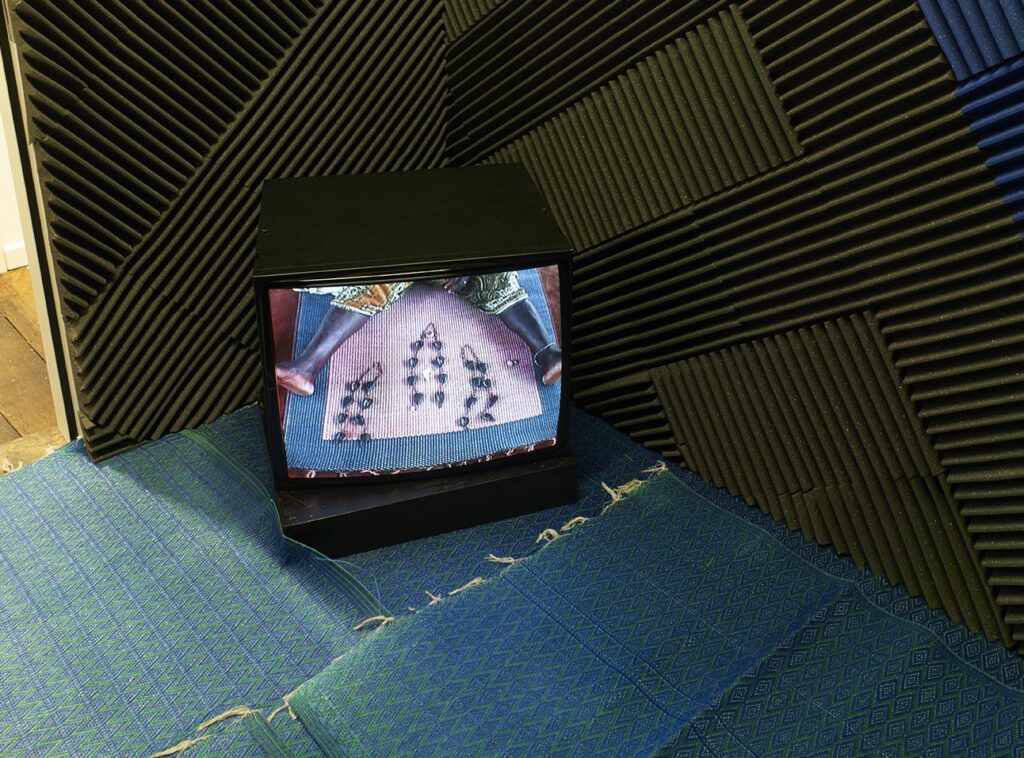

Installation view, Atopolis, Mons 2015. Kapwani Kiwanga, Untitled (2015) (detail), Photo: Kristien Daem

What I like most about Atopolis is that it not only started with a mistake but that the envisioned ideal city is not a carefree zone and has its own cracks, failures, and pauses. In our neo-liberal capitalist society of the “just do it!”, Atopolis opens up a space for the qualities of hesitation and doubt. Nevin Alada?‘s “Leaning Wall”, decorated with the porcelain imprints of female and male body parts, leaves the spectator pondering if one could fit in, if one should fit in to make it higher, or if it would be possible to break the mold. A little further one can lounge in Alada?’s “Music Room” – a performative conversation piece between 1970s German furniture and Kurdish and Turkish instruments. In between there’s Paul Lafargue’s “Le droit à la paresse” of 1883. Adrian Melis gives the right to be lazy a sound in collaboration with the employees of a Cuban factory, whereas Walead Bestly takes us to an office where the printer refuses to perform.

Installation view, Atopolis, Mons 2015. Abraham Cruzvillegas, The Simultaneous Promise (2011) – In the back: Jack Whitten, Atopolis: For Edouard Glissant (2014), Photo: Kristien Daem.

There’s no doubt, however, that Utopia must have the color of gold. El Anatsui is not being cynical with his golden wall piece woven out of trash. It is beautyful and, more over, has been produced under socially correct circumstances, which, even in the arts, is not as obvious as one would think. We know that Utopia in the end transcends matter and upon seeing that Danai Anesiadou has vacuum packed all her belongings, one can’t help the feeling of relief: with the material wrapped up, is the immaterial set free? Kapwani Kiwanga talks about spirituality by bringing together the Yoruba Ifá divination and the decimal classification system by Paul Otlet. Both religion and science are looking for the same: a knowledge of hidden and invisible things like the future. But let us finish by looking backwards, into the multiple rear view windows of Abraham Cruzvillegas’ motorbike. By doing so, we’re no longer trapped in our own restrictions of reality but can catch a momentary glimpse into those other realities, the ones that fractioned off in dreams.

An Paenhuysen works as a freelance curator, art critic and educator living in Berlin. She is a fervent art blogger and teaches art criticism online at Node Center for Curatorial Studies.

More Editorial