Obama's fine selection of works from Glenn Ligon to Alma Thomas is going to leave the White House. But what's coming instead?

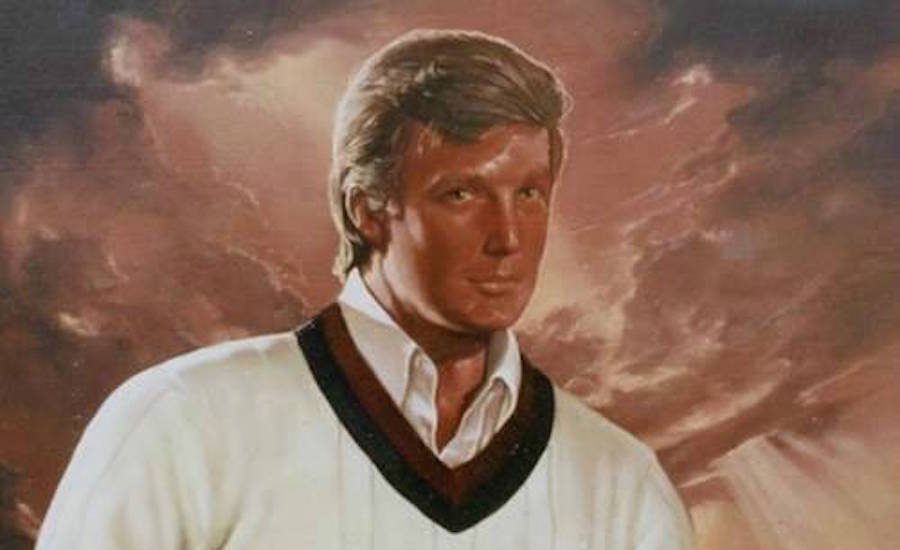

Portrait of Donald Trump by Ralph Cowan

The family sitting room of the Obama-occupied White House includes a text-based painting by Glenn Ligon. “All traces of the Griffin I had been were wiped from existence,” reads the text in Ligon’s oil and gesso on canvas, Black Like Me #2 (1992). The loaded sentence, a quote from white journalist John Howard Griffin’s nonfiction book Black Like Me (1961) about his investigative journey into the racist Deep South, repeats itself, right to left, row after row, until the words thicken and grow illegible as the canvas blackens. The work is owned by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, but has been on loan to the White House since 2009 when the Obamas redecorated this stodgy bastion of white privilege.

.

.

The revamp, which involved placing some four-dozen works by mostly male artists, was in many respects conventional. Think mahogany grandiosity leavened with easy-on-the-eye abstraction by Sean Scully, Robert Mangold and Mark Rothko. Think preppy couple inheriting and then redoing grandma’s mansion.

.

The Old Family Dining Room of the White House, revamped by the Obamas and with a great work by Alma Thomas in yellow, red, and blue. (Official White House Photo by Amanda Lucidon).

But the Obamas also made some strategic choices, which, even now, resonate as tactical interventions, bearing out something David Hammons once said: ”magical things happen when you mess around with a symbol”. On display in the West Hall is an abstract canvas in blue by Alma Thomas, a neglected African-American abstract painter who - like Beauford Delaney and Norman Lewis – never received the acclaim she deserved in her lifetime. Sky Light (1973), one of two works by Thomas, would hold its own next to any of Yves Klein’s blue monochrome paintings from the early 1960s.

.

It is widely speculated that one of the first things president elect Donald Trump will do is renovate the interiors of the White House. It is a trifle compared to this engorged ego’s spoken threats, among them a storied wall. Still, in a world where what you say is increasingly matched by visual affirmations of who you are – be it identity, romantic entanglement, locatedness, class, narcissism, love for Mexican food - pictures matter. Trump’s proclivity for beatific art – his Trump Tower suite is a pastiche of Renaissance styles that screams new Russian oligarch – suggests that the White House will in 2017 revert to painterly figuration in gilt-frames. Trump has little interest in metaphor.

.

Will the White House soon transform into this ? Donald and Melania Trump’s New York City penthouse is on the 66th floor of Trump Tower and features marble walls, floors and columns throughout. 24-carat gold accents like platters, lamps, vases and crown molding that outlines each room and tableau ceilings. Copyright: Sam Horine. Source: Daily Mail

.

In 1999, during the storm surrounding Chris Ofili’s 1996 painting, The Holy Virgin Mary, then on show at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Trump, stated: “As President, I would ensure that the National Endowment of the Arts stops funding of this sort of art.”

.

Back then his me-too angle on a media controversy was cute; but as of 2017 it will define the national compass. Trump, who described Ofili’s work as “absolutely gross, degenerate stuff²”, will likely feel little kinship with Ligon’s reminder of the Jim Crow South. Or be willing to project that permablond ego of his into little known abstract panier Edward Corbett’s 1963 work Washington, D.C. November 1963 III, which during the Cold War decorated the US embassy in Belgrade.

Works by Ligon, Thomas and Corbett will be returned to their lenders. This begs a question: will the transformation of the White House into a dude palace by a man with a proven animus to people of colour push back the gains of African-American artists over the past few decades?

More Editorial