A review about the 45th edition of the Rencontres d’Arles 2014 by our author Dagara Dakin

Rencontres d'Arles 2014 (courtesy of Dagara Dakin)

The 45th edition of the Rencontres d’Arles, entitled “Parade,” left us underwhelmed on the whole. Perhaps we were expecting a bit too much from the most recent festival under the leadership of François Hébel, who directed the iterations of 1986 and ’87 as well as those from 2002 to 2014.

In any case, out of fifty-some proposed exhibits, barely a dozen saw the light of day. Of these, the exhibition of the Walther Collection was the most compelling, although it would be unfair to neglect the slideshow “Identities, Intimate Territories” by Denis Rouvre, the retrospective of the Pictet Award, or the installations by the MYOP collective that were presented alongside the official festival.

Nonetheless, let us not be distracted here by anything but the Walther collection, which shone for the clarity of its intensions; the exhibit organized by OFF the Wall magazine, whose dynamic force merits recognition; and finally, the festival’s “Prix Découverte” rising star awards, as part of which Nigeria’s Azu Nwagbogu – founder and director of the African Artists Foundation among other things – chose to present the work of Kudzanai Chiurai and Patrick Willocq.

The Walther Collection

The Walther Collection, which was first opened to the public in June 2010 in Neu-Ulm/Berlafingen, in southern Germany, was much remarked upon for its inaugural exhibit curated by Okwui Enwezor. Entitled Event of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity, that exhibit opened a dialogue between three generations of African artists and photographers, on the one hand, and a selection of contemporary German photographers, on the other.

On the ground floor of the current exhibit, divided into two stories of the Espace Van Gogh in Arles, we once again encounter this confrontation between the work of African photographers and their German counterparts. Meanwhile the walls of the second floor were hung with photographs by Asian artists such as Ai Weiwei and Nobuyoshi Araki.

Curated by Brian Wallis and co-produced by the Rencontres d’Arles, the exhibition is the first half of a two-part series presenting Artur Walther’s collection in France. The second half will be on display in October 2015 at the Maison Rouge in Paris.

The selection, presented under the title Typology, Taxonomy, and Seriality, assembles a range of modern and contemporary pieces. We come upon photographs by Karl Blossfeldt and August Sander, more recent work by Bernd and Hilla Becher, Richard Avedon, J.D. Okhai Ojeikere, Samuel Fosso, and Zanele Muholi, not to mention Kohei Yoshiyuki, as well as a series documenting a performance by Zhang Huan, and the list goes on.

The arrangement, organized both chronologically and thematically, also serves as a reflection on the medium itself. According to the description by collector Artur Walther, the exhibit addresses “how conceptual performance, serial portraiture, and time-based work have developed around the globe.”

The social and political theme gradually reveals itself, particularly in the room that juxtaposes the series The Family, comprising 69 portraits of powerful American figures taken by Richard Avedon in 1976, against a 2011 series of 42 portaits by Accra Shepp depicting Occupy Wall Street protesters and their wide range of demands denouncing social inequality.

The first level largely grapples with social and political questions through the genre of portraiture, with several exceptions including a series of images of industrial sites taken by Bernd (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (b. 1934) in the late ’50s. The second level is devoted to Asian photographers and concludes with the theme of sexuality as explored in the works of Nobuyoshi Araki and Kohei Yoshiyuki. This discrepancy of themes does not keep the visitor from discovering formal patterns throughout the art on display.

It is interesting to see, all in one place, the portraiture of August Sander (1876–1964), Seydou Keita (1921–2001), Malick Sidibé (b. 1936), and the Hairstyles series by the late JD Okhei Ojeikere (1930–2014). The commonalities speak for themselves even though we are aware that the images were captured across a range of periods and contexts out of an equally broad range of intentions. This mutual confrontation reveals to us, for instance, the sociological dimension of the portraits taken in the ’60s by the likes of Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibé. The portrait artists of Bamako who photographed diverse strata of Mali society arguably did so without any aim whatsoever of inventorying the population that frequented their studios. In contrast, with his grand sociological fresco-èsque series People of the 20th Century, August Sander proceeded methodically to take a visual census of the professions and social groups of 1930s Germany. The rigorous approach followed by Sander found an echo in the Hairstyles series by JD Okhei Ojeikere beginning in the 1960s.

One of the exhibit’s major successes is the alternative reading it provides for the work of African photographers, placing them in dialogue with the creations of major players in the history of European photography. Furthermore, the chronological presentation highlights the shift in practices that occurred on the African continent in the early 1990s, arising in large part out of the sudden influx of interest from the international art world in the work of African artists.

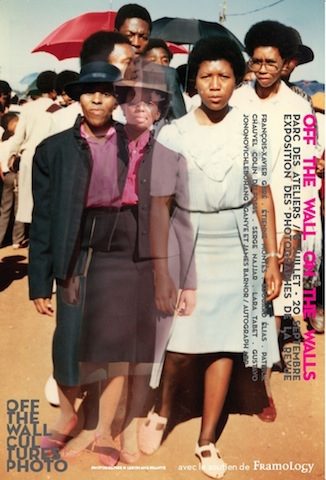

OFF the Wall on the walls

OFF the wall © Rencontres d’Arles 2014

On another vein entirely, the young photo magazine OFF the Wall chose the brand-new building of the Parc des Ateliers as the site for its exhibition of ten established and emerging photographers featured in the publication’s first four issues. “The site was generously lent to us by the LUMA foundation and the exhibit was produced by Framology, a new printing and framing outfit,” explains Anna Alix Koffi, curator of the exhibit and creative director of the magazine.

The exhibit, entitled “OFF the Wall on the walls,” presents images by Lara Tabet, Serge Najjar, Gustavo Jononovich, François-Xavier Gbré, Etienne Montès, Edouard Elias, Patrick Chauvel, Colin Delfosse, Lebohang Kganye, and James Barnor. Barnor participated with the support of Autograph ABP, a London-based funding body.

The OFF the wall project, launched on 27 April 2013, is entirely independent. Its initiators hope to run it through sponsorship and purchases by gallery spaces and brands interested in photography. According to the editorial in the first issue, the magazine is placing its stakes on “paper (that beautiful thing) in this era of digitalization, because there is no better surface for photography.” The project is limited to ten volumes with a print run between 500 and 1000 copies.

I have no desire here to critique an endeavor whose foremost aim is to promote the work of a specific set of photographers. Rather, let us stress the sheer drive of this fledgling photo magazine, which plans to release three issues per year until the final issue slated for 2016.

Bringing selected work by the photographers the magazine supports to Arles, and thereby repeating what the publication has already achieved earlier this year in Paris and elsewhere, is one way for Anna Alix Koffi and her collaborators to draw a different kind of attention to the artists’ efforts. Without a doubt, the initiative serves as an admirable building block to complement the edifice of the contemporary photography market. We hope it will play an active role in dismantling the cloak of invisibility that still isolates some excellent artistic ideas.

The Prix Découverte

Since 2002, the “Prix Découverte” has been awarded to a photographer or an artist employing photography whose “work has recently been discovered or deserves to be so.”

The judges, “photography experts from five continents who program festivals and/or work at institutions,” each nominate two artists for the award. This year, the five experts charged with making nominations were Quentin Bajac, Alexis Fabry, Bohnchang Koo, Wim Mélis, and Azu Nwagbogu.

The 2014 Prix Découverte was awarded to the photographer Kechun Zhang, born in 1980 in Bazhong, China, for his series entitled Yellow River, a dreamlike and contemplative documentation of life around the eponymous waterway. Zhang was nominated for the honor by the Korean curator Bohnchang Koo.

Azu Nwagbogu, the curator assigned to present African photographers, chose to show work by Kudzanai Chiurai and Patrick Willocq. We had serious doubts regarding this choice as, in our view, the two artists’ work is preoccupied with technique, and although their intentions are commendable, their execution is approximate at best. For example, what exactly is Patrick Willocq trying to say with the stage-managed images of his series I Am Walé Respect Me? His approach, which aims to revisit the iconography of anthropology, strikes us as incomplete. As for Kudzanai Chiurai, one wonders whether he has made the most appropriate aesthetic decisions in order to capture his subject of the recurring violence in Africa. These works demonstrate an undeniable mastery of technique, to be sure, but that is not enough to overcome the unclarity of both artists’ intentions. After all, in art as elsewhere, clear intentionality is just as crucial as follow-through.

In general, photographs from the African continent were still only meagerly represented at Arles. Yet the movement in that direction made by Artur Walther’s collection is much more encouraging.

Let us cross our fingers that the progress will be more pronounced in the next edition of the Rencontres, this time under the guidance of Sam Stourdzé, the former director of the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne.

Based in Paris, Dagara Dakin is a graduate in art history, writer, critic, and independent exhibit curator.

More Editorial