In the new series Don't Mourn, Organize! we ask artists, writers, curators during the next couple of weeks and months: How can we form a creative perspective to react to the current status quo?

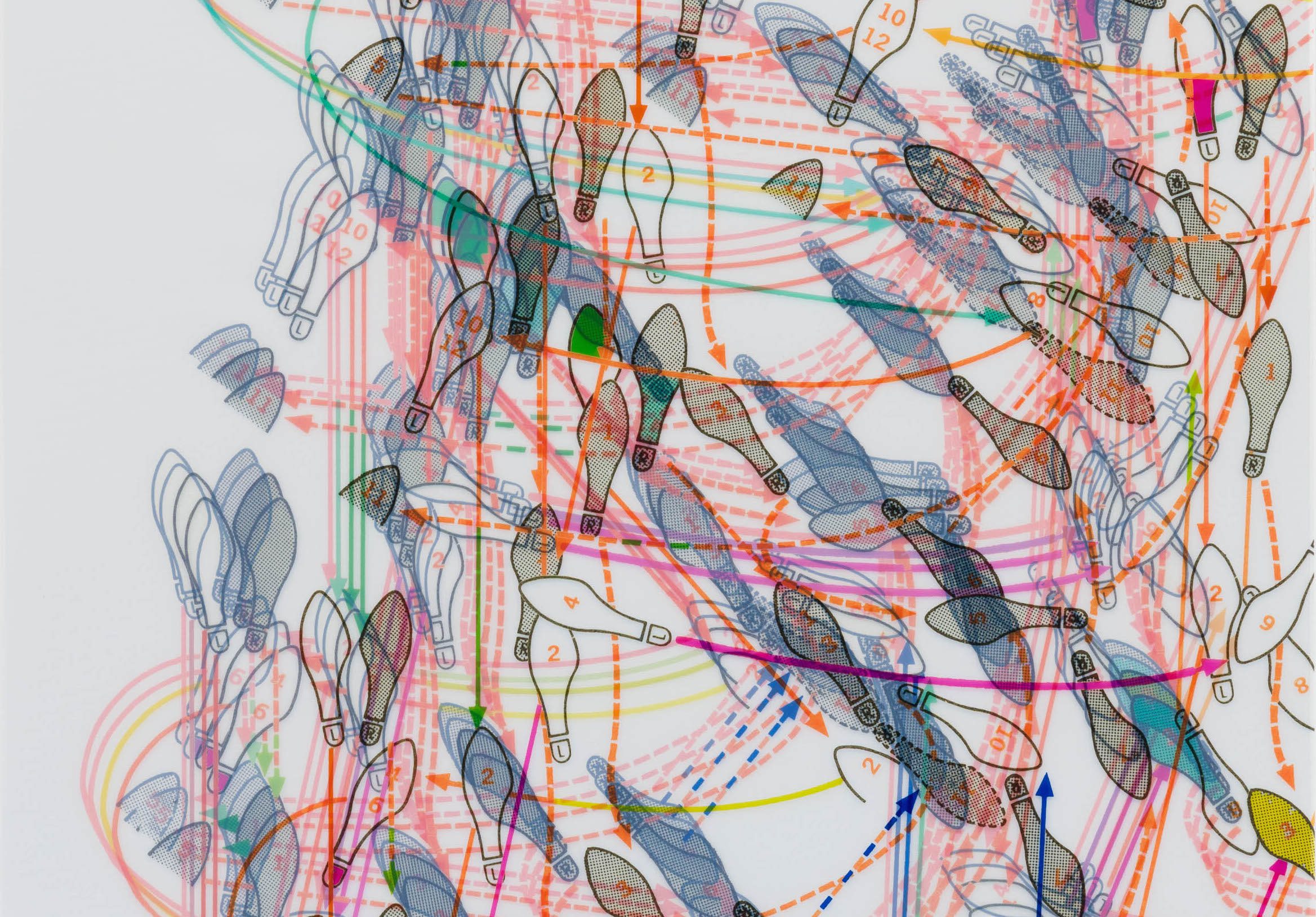

Jibade-Khalil Huffman, 'Dance Card or, How to Say Anger When You Lose Control’ ‚ 2017, inkjet on transparency and canvas. Courtesy of the artist

Renowned artists who have lived in the US for decades told us they are seriously considering not returning to the US as long as Donald Trump is in power. An influential curator from New York emailed us the day of the election, still completely in shock: “Winter in America. It’s certainly tough here. But folks feel ready to fight!“ We have received many similar statements by artists, curators, academics, writers – emotional, powerful, concerned reactions to the current status quo. In the new series “Don’t Mourn, Organize!” our question to them during the next couple of weeks and months will be: How can we form a creative perspective, how do we react by not solely concentrating on the uncertainties and crises but instead transforming ideas into platforms and strategies for change?

.

C&: James Hetfield, the front man of Metallica, recently said in an interview that Trump’s election wouldn’t affect his ongoing work. In a sense, he doesn’t want to give the new government the power to influence his artistic production. What is your perspective here in terms of your art? Will that election impact your work?

Jibade-Khalil Huffman: For those of us for who were not hugely surprised by the results of this election, the idea of anything being different and, accordingly, of working to persist in spite of some new set of obstacles is in some ways laughable. For me it only feels scarier because we are one degree closer to real disaster, whatever real disaster means in light of daily briefings about some newly threatened right. We were three degrees away, maybe three and a half with Obama (deducting the half-point from his legacy for all the drones and a few other matters I won’t get into here). And now we are all, and I mean all of us, on a precipice. I’m sorry the world is a little scarier for James Hetfield but – proud of his resilience? I guess?

C&: What is your perspective on the status quo from the perspective of a citizen, an artist?

JKH: There are several status quos in the art world, not just a mainstream, auction/art fair/collector pandering/afterparty as more important than the Afterimage zone of bullshit (or a different and better way of putting it is that there are several art worlds). The status quo is best distilled into a solid form as the press release or more generally under the umbrella of public relations. Outside of this, even in the painting machine, there is the potential for weirdness or whimsy and real joy (as well as an acknowledgement of the tragedy and weirdness of death and the like) but public relations smooths all this out into, essentially, a readable elevator pitch. In the future, if the status quo has its way, there won’t be objects or even fully formed ideas anymore but only tweets of elevator pitches.

.

Jibade-Khalil Huffman, installation view, Kush is my Cologne, 2017, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, pictured (foreground) Untitled (blank verse), 2017, inkjet on transparency (background) Set, 2016, inkjet on canvas. Courtesy of the artist

.

C&: You once said you believed that with the passing of time and the influence of natural and unnatural forces (globalization), the only remaining barriers are language and the shallow details of local customs. You are a poet as much as a visual artist. What does language mean to you? And what would the “shallow details of local customs” be for you?

JKH: This is honestly the question I most dread answering (and I am often asked) mostly because this way of working is so second-nature to me. Language is the primary way I work through ideas, although I also, in terms of the public, started to and continue to make objects that are primarily visual because of the occasional failure of language to address the matter at hand. It’s like the difference between illustration versus caption and object vs. words being thought or spoken by an individual.

C&: What is the relationship between text and image for you? You work with video and photography so, to be more specific, what is the relationship between photo, moving image, and text?

JKH: I like to think that I read things visually and that I can, when I am not reading for the particular and primary purpose of gleaning information, “see” words on the page in their relation to everything else in the world. I also don’t want to dwell on hierarchies. In some cases, you need hierarchies. For example, to continue my illustration and caption metaphor from above, in many cases you need for the picture to be bigger and for the caption to aid in your understanding of this visual record of the event as opposed to a picture and text that deconstruct the idea of pictures and captions and therefore unintentionally distract from the point. But sometimes the point is this confusion of scale. Most of the work that I make that employs text and image is about addressing this confusion (at, say, the indescribability of certain visual phenomena) in the world. The question of the relationship between photography and video is perhaps, or at least to me, more interesting. In one way it’s simple and has a lot to do with necessity (this act or object is better suited for the world as a moment frozen in time – though still, of course, fluid in its implications – or as a record or version of an entire series of moments) and yet the whole thing becomes that much more interesting when you think about a static video image as a version of a photograph or something else entirely.

C&: You are interested in the subject of therapy versus religion in the African American community. Why? And what are the outcomes of you looking into this subject?

JKH: I definitely don’t mean for this to be a cut-and-dried, one-or-the-other bifurcation of remedies for black folks. However, in the scheme of making that particular exhibition (Stanza at the Studio Museum) I realized I wanted this idea of things in opposition hanging over the whole thing. It’s much more complex now than, say, when Fredric Wertham opened the first mental health clinic in Harlem but there’s a kind of one or the other (and I’m generalizing here, course) that has only changed somewhat recently with the ubiquity of the term and practice of “self-care.”

.

Jibade-Khalil Huffman, Installation view, “Kush is my Cologne,” 2017, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, pictured (l) “Untitled (acid rap),” 2017, archival inkjet print (r) “By the Author of Another Country and Nobody Knows My Name,” 2017, transparencies in lightb

.

C&: This topic – and broadly speaking the context, experience, and tragedy of black communities – is a major issue that concerns you. Does that make you a political artist? Is your art political?

JKH: I wouldn’t say that I’m a political artist, though I also think that most art is at least kind of, sort of political, if only insofar as it is or can be a reflection of a certain condition. The very gesture of painting, even in abstract terms, which is to say, memorializing a subject through this act, is a political gesture. I believe I’m more interested in criticality, which is a mode that is, I think, has a little less potential for being corrupted than being beholden to certain ideology. Criticality implies, for me, holding a number of ideologies at odds and in harmony with each other. And I think this is more useful in terms of living as well as making things or ideas.

C&: Do you want it to have an impact beyond the art world?

JKH: Definitely. I’m maybe too impatient for the art world anyway. For me, corny as it may sound, it’s about working through the best way to deal with ideas and more importantly, where and how these ideas are received by a public. As such, changing the form to better suit an idea is more important than figuring into the history of a particular medium or some other nonsense. As ever, I care more about the idea.

.

More Editorial