In this series, C& is revisiting the most discussed, loved, hated, thought-provoking, and game-changing exhibitions featuring contemporary art from African perspectives in the past decades. We unearthed a review by Bisi Silva taking a closer look at the second - and last - Johannesburg Biennale.

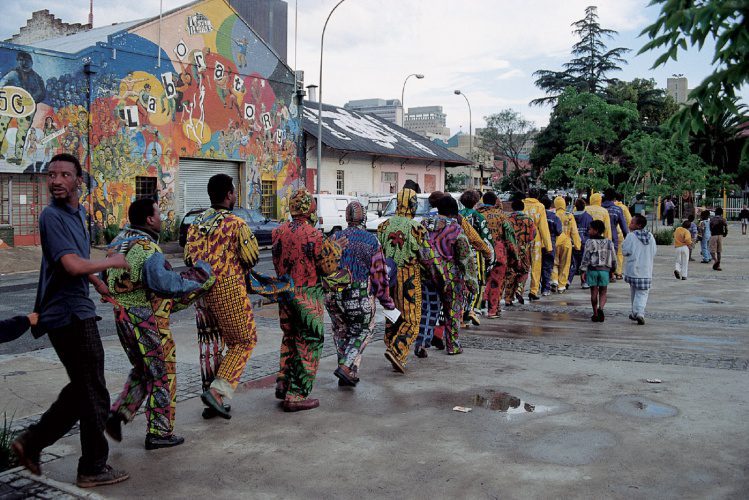

Studio Orta, Nexus Architecture. Nexus suits created together with migrant labourers from the Usindiso shelter in Johannesburg for the second Johannesburg Biennale, 1997

The recent boom in Biennales and mega-exhibitions especially outside the center of the Western art metropolis made 1997 an exceptionally busy year for the jet-setting art-trailer, in addition to the well-established and handsomely financed purveyors of contemporary art in the West, there are the less highly profiled biennales which are gaining importance in giving a truly global perspective of current trends and preoccupations in visual art and culture. Documenta X, The Munster Sculpture Project and the Venice Biennale were joined in 1997 by the Havana, Kwangju, Istanbul and the Johannesburg biennales, not to omit the smaller Eastern European ones such as in Slovenia that are proliferating.

Biennales or mega-exhibitions currently seem to be a prerequisite for any nation wanting to rejoin the global village. After decades of isolation. South Africa is another eager entrant whose post-apartheid optimism and euphoria continues unabated. As a signal of its arrival on the international cultural scene. South Africa hosted its first Biennale in 1995, a landmark event that included over 250 artists from 80 countries. Under the artistic direction of the Nigerian born, American based Okwui Enwezor, the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale entitled “Trade Routes: History and Geography”, takes the concept of “global traffic in culture” as its curatorial and philosophical point of departure.

Moshekwa Langa, Temporal Distance (With a Criminal Intent) You Will Find Us in the Best Places, 1997, mixed media installation, photo: Werner Maschmann

Veering away from the traditional format of biennales based on national pavilions, which inevitably reinforce the binary axis of rich/poor, developed/ underdeveloped, Western/non-Western, Enwezor decided to collaborate with six international curators: Kellie Jones, Gerardo Mosquera, Octavio Zaya, Hou Hanru, Colin Richards and Yu Yeon Kim. They were invited to engage with and respond to the discourses engendered in “Trade Routes” such as postmodernism, post- colonialism, popular culture, multiculturalism and issues of identity that take into consideration racial, cultural, historical, gender and sexual differences.

The result is a smaller biennale in which we are presented with a series of very diverse exhibitions consisting of an array of works in a variety of media from over 145 artists from 35 countries. Installation-based conceptual art over- whelmingly dominated, though pho- tography, film, video, and sculpture were well represented. However, the paucity of painting in such an interna- tional exhibition almost gives credence to the much lamented death of painting. As the centerpiece of the Biennale the exhibition, “Alternating Currents”, was housed in a huge, unusual but beautifully renovated former power gener- ating station built in 1929, with the entrance dominated by the imposing work United Nations — Africa Monument: Oasis 1997, by Chinese artist Wenda Gu. The installation, hung like a 30 foot wall carpet, consisted of real hair col- lected from over 300 barber shops world-wide.

Co-curated by Enwezor and long-time collaborator, curator and critic Octavio Zaya, “Alternating Currents” is a rambling exhibition in which no dis- cernible trajectory is visible and any at- tempt at a single thematic underpinning dissipates. This does not prove to be a hindrance but actually allows one to ap- proach the exhibition as a free for all ‘zone of encounters’ in which eighty odd artists are invited to participate in and respond to several all encompassing concepts that begin with ‘post’ and end in ‘ism’ or ‘tion’: post-modernism, post-colonialism, post-nationalism, globalisation, migration. Nonetheless these are important themes which surface repeatedly in the works of many artists and the twin concepts of “History and Geography” more than any other determining factor provide a focal point for challenging fixed ideas of boundaries, borders against the changing landscapes which significant- ly characterize the latter part of the 20th century.

“Trade Routes” is conceptualized around political, cultural and economic issues and brought together a wide vari- ety of works such as the installations of Yinka Shonibare, Vivan Sundaram and Marc Latamie. In the Victorian Philanthropist Parlour, 1996, London- based Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare recreated a Victorian parlour with the furniture and walls decorated in African batik, a material widely thought to originate from Africa. However, in making his point about the way travel affects notions of cultural identity and questions of authenticity, the artist has traced the origin of the fabric from Indonesia to Holland to Britain to West Africa. Indian artist Vivan Sundaram’s acerbic installation The Great Indian Bazaar, 1997, uses text and photographic images on steel to highlight the effects of global com- merce and the influx of consumer goods in a country where the majority population can barely afford them, whilst Martiniquan Marc Latamie’s work, Side Effects, 1997, a recreation of what seems to be an import and export office conjures up the human consequences of the global trade in coffee, sugar and cotton.

Diaspora as a result of forced, voluntary, economic or political migration is a thread that runs through many artists work. This is not surprising as a perusal through the copious biennale catalogue indicates that over half of the artists are settled in countries other than that of their origin. The process of remembering, recapturing and revisiting is depicted in the South Sea Island and Africa series, a photographic installation by African American artist Carrie Mae Weems in a search for her African ancestry outside of the American context which takes her on a pilgrimage along the Slave Coast to Senegal, Ghana and Ivory Coast. However migration and memory was depicted no more poignantly than in Mexican Teresa Serano’s three screen video pro- jection The Grass is Always Greener on the Other Side of the Fence, 1997, of thousands of monarch butterflies migrating northward which is subse- quently superimposed every few minutes with grim images of human migra- tion as a result of famine, war and other disasters.

The strength of “Alternating Cur- rent” lies essentially in bringing to South Africa the work of international- ly acclaimed artists such as Gabriel Orozco, Felix Gonzales Torres, Beat Streuli, Sam Taylor-Wood, Shirin Neshat, Stan Douglas, Rona Pondick, Ghada Amer and Eugenio Dittborn. It also succeeds in introducing South African artists that are well-known lo- cally such as Penny Siopis, Sue Williamson, Andries Botha, Malcom Payne, Wayne Barker, to an interna- tional audience. Striking examples were Santu Mofokeng’s slide projection of archival photos Black Photo Album/ Look at me 1890-1950, 1995-97 in w h i c h some of the images depict working and middle class black people dressed in complete Victorian attire, constructing a portrait of how they imagined themselves. Mofokeng intercuts these im- ages with texts that analyze what he calls mental colonization. The images were even more striking against the contemporary portraits by Zwelethu Mthetwa of ordinary black folk and the simplicity of the way they actually live.

Vivienne Koorland, Terezin Painting: Josef, 1991, oil on linen set in wood mantle, photo: Werner Maschmann

The other Biennale exhibitions tried to achieved some coherence mainly through the association of media. The photographic element dominated “Important and Exportant” by Cuban curator Gerardo Mosquera. In spite of the beautiful installation in the spacious Johannesburg gallery of Art, it was overall a staid affair, saved only by some interesting juxta- positions such as Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Seascapes with Brazilian Cildo Meireles installation Morulho, 1992-97, which consists of a pier surrounded by 2,000 printed open books laid out on the floor of which all the colors are emerald blue, creating a simulated impression of the sea.

As we approach the end of the century, the impact of technology has become more prevalent and constitutes an integral part of big exhibitions. “Hong Kong, etc” by Paris based, Chinese curator Hou Hanru contains a 110 page website which though it included text, project pages, and art contributions by luminaries such as Rem Koolhaas and Saskia Sassen proved — even when technical difficulties were overcome – to be tedious and time-consuming in accessing the information. The Rembrandt van Rijn Gallery was an uninspiring space which did a disservice to the work by Andreas Gursky, Huang Yong Ping, Ellen Pau and Fiona Tan. “Transversions” achieved a more successful combination of traditional media and new technologies. Located on the two top floor of the Museum Africa, the curator Yu Yeon Kim used film, video, sculptural installations and computer terminals to provide a well- rounded but diverse exhibition that included work by Alfredo Jaar, Gary Simmons, Dennis Oppenheim and Keith Piper.

“Trade Routes” continued its journey along the confluence of the Atlantic and the Indian oceans at the Cape of Good Hope to “mark the tangible geographical site around which globalization is discussed.” Consequently Enwezor strategically expanded the parameters of the biennale to Cape Town. Lacking the shadow of potential danger that almost crippled movement in Johannesburg, Cape Town is almost surreal as one tries to remember that one is not actually on the Cote d’ Azur or any other European Riviera but in Africa. In spite of all the other coastal distractions the two exhibitions are the most fo- cused. “Graft” curated by South African art historian and curator Colin Richards concentrates entirely on the work of South African artists living in and out of the country and included the work of younger artists such as Johannes Phokela, Moshekwa Langa, Maureen de Jaeger, Tracey Rose, Sandile Zulu, etc.

“Life’s Little Necessities” by Amer-ican curator Kellie Jones explored the way in which women artists use installation in the 1990s to explore a myriad of different but interconnecting issues. Americans Lorna Simpson and Jocelyn Taylor both used film projec- tion and video to explore issues of the body and erotica whilst Nigerian artist Fatimah Tuggar and South African Veliswa Gwintsa explored the domestic space. The latter by questioning the traditional bride price. The former by creating huge computer-generated images that superimpose African traditional kitchen with modern high-tech Western one highlighting the fusing of roles and culture.

To complement the exhibitions an ambitious film programme presenting work by over 30 filmmakers from over 20 countries were screened. Also available was a public art programme that included posters, billboards and performance art. Unfortunately in spite of the efforts and well placed intentions to involve the local community and make the Biennale reach the widest audience possible, it was hindered by the lack of proper or any advertising. As little or no information and directions was available, most of these public pro- grammes not only proved difficult or impossible to find, they escaped the attention of the most avid art trailer and a local audience not used to looking for or engaging with art in alternative spaces.

At the Biennale press conference, and in spite of South African artists representing over a quarter of the participants, questions around the relevance of some of the work and the issues to their lives, their conditions in Johannesburg, in Cape Town but most of all in the townships were continuously asked. Like any event of this size and in such a complex country as South Africa where the majority of the people are still in the throes of disenfranchisement, it is difficult to justify the necessity of a cultural event such as the biennale. Maybe Johannesburg needs to find a format that — in view of local preoccupation and the desire of the organizers to reconnect with their neighbors —will work for the African continent without the forfeit of its global aspirations. “Trades Routes: History and Geography” is a beginning.

Bisi Silva is an independent curator and is founder and artistic director of the CCA Lagos, Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos. She was the Artistic Director of the 10th Bamako Encounters: African Biennale of Photography.

This article originally appeared in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art in 1998.

EXHIBITION HISTORIES

LATEST EDITORIAL

More Editorial