The Black, Asian and White Racial Triangulation

24 September 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min read

Contemporary And (C&): The racial triangulation between Blacks, Asians, and others (whites) is something that occupies you. Among other things, this was instigated by the work of Claire J. Kim, who has related the experience of Asian American and African American communities. Could you talk a bit about this approach? kate-hers RHEE: While I was …

Contemporary And (C&): The racial triangulation between Blacks, Asians, and others (whites) is something that occupies you. Among other things, this was instigated by the work of Claire J. Kim, who has related the experience of Asian American and African American communities. Could you talk a bit about this approach?

kate-hers RHEE: While I was a graduate student I took a class with political scientist Claire J. Kim at the University of California, Irvine. For me this was a profound moment as I drew upon my confounding experiences growing up as a non-white, non-Black person, in a severely racially segregated Detroit suburb and attending college in the similar racially tense city of Chicago. In her theory of racial triangulation, Kim argues that, Asian-Americans “… have been racialized relative to and through interaction with whites and blacks. As such, the respective racialization trajectories of these groups are profoundly interrelated.”

Racial triangulation materializes through two processes which ultimately serve to reinforce white power and privilege. The mainstream valorizes Asians over Blacks, citing Asians’ hard work ethic and material successes and implying deficiencies in the latter. Yet unlike Blacks, Asians continue to be inherently alien, apolitical, and unassimilable to mainstream culture, and never perceived as true Americans. In the 1960s, Asian-Americans were dubbed “the model minority” and since then, this myth has plagued the relationship between Asian-Americans, the “good minority,” and Blacks and Latinos, the “deficient minorities.” As I encountered the perception of Blackness by the white German mainstream, I couldn’t help but consider what impact that had on perceptions of Asianness.

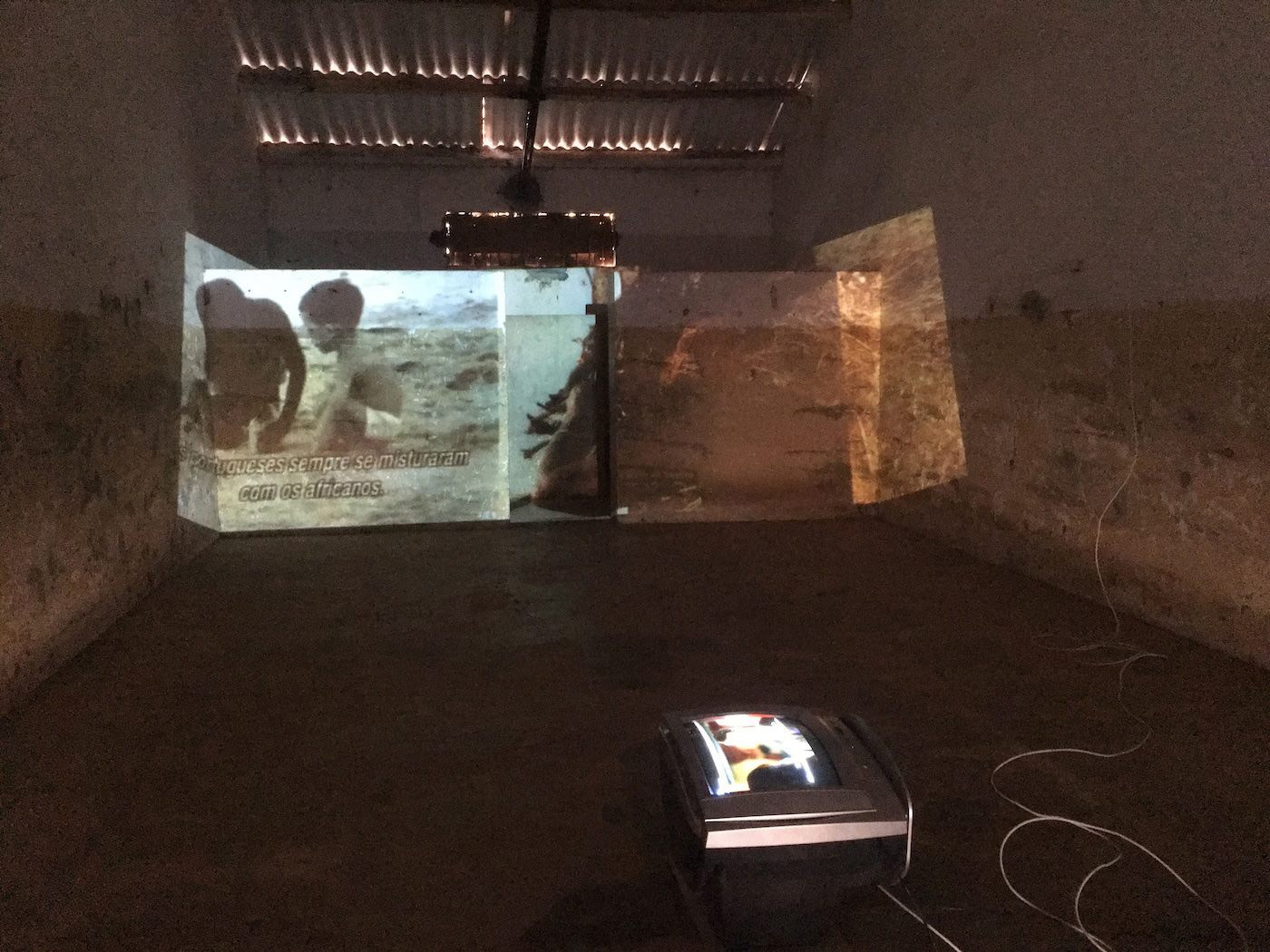

<figcaption> kate-hers RHEE, Black Projection Grid 1, 2, 3, ©2014, each work consists of 49 corks on wood panel, 30 x 30 cm, photo credit: Aleks Slota

C&: You have analyzed your experiences as a South Korean-US American artist based in Berlin. As one reference point, you have used the experiences of Black people. What were your findings in relation to your own experiences?

khR: One of the reasons I think I started looking at how Black people or Black culture is portrayed in German culture and language is because it struck a nerve close to home for me, given my background of constantly having to locate myself in between the minority and majority. However, I want to underscore that rather than dealing with the direct personal experiences of Black people, I point to the ways in which Blackness is represented through the white mainstream, for example the German Schokokuss (sweets which used to be called a pejorative name, N-kiss). In making all these pieces, I call attention to my position as a non-Black, Asian-American artist. Some questions that I was grappling with: What does it mean for a non-Black person to deal with Blackness? How can I contribute to a discursive conversation about race when the framework for speaking exists frequently only in Black and white terms? I consider my role in naming and calling out injustices towards Black people essential for me to understand and overcome my own oppression, not only as a victim of discrimination but also as someone who possesses implicit bias. Any type of Othering affects all of us who are standing outside of the norm.

<figcaption> kate-hers RHEE, Fidschi Saft für eine Gute Reise nach Hause (Fiji Juice for a Nice Trip Back Home), Installation shot at SOMA Gallery - Berlin 2017, 5 Fiji Water Bottles and the Artist’s Urine, 24,5 x 7 x 7 cm, photo credit: Aleks Slota

C&: In that sense you are interested in the complex trajectories bodies of People of Color take as they get (re)produced, reduced, and essentialized. One example is the work Fidschi. Could you tell us more about that work?

khR: I first encountered the insult “Fidschi” my first year in Berlin, in 2009. I was walking with an Asian-German friend outside of the Eberswalder Metro Station when we accidentally walked in front of two white men, cutting them off on the pedestrian walk. One of the hooligans called us “Fidschi.” New to Berlin and to the German language, I had no idea what he was saying. I recall being impressed with my date as he nonchalantly told our verbal assailant to “Verpiss dich! As we showed no signs of emotional response, the racist proceeded to get hysterical and started shouting obscenities. A few years later while at a subway station, I overheard a man who had just asked me for a cigarette cry out, “Wo sind die verfickten Fidschis?” He had apparently expected me to be selling illegal cigarettes.

This new work is called Fidschi Saft für eine Gute Reise nach Hause (Fiji Juice for a Nice Trip Back Home), which consists of Fiji water bottles filled with my own urine. The word “Fidschi” has its origins in the GDR when those of Vietnamese or other East Asian descent were discriminated against and subjected to this pejorative insult. The title of the work references the refrain of the song by the neo-Nazi band Landser: “Fidschi, Fidschi, Gute Reise“.

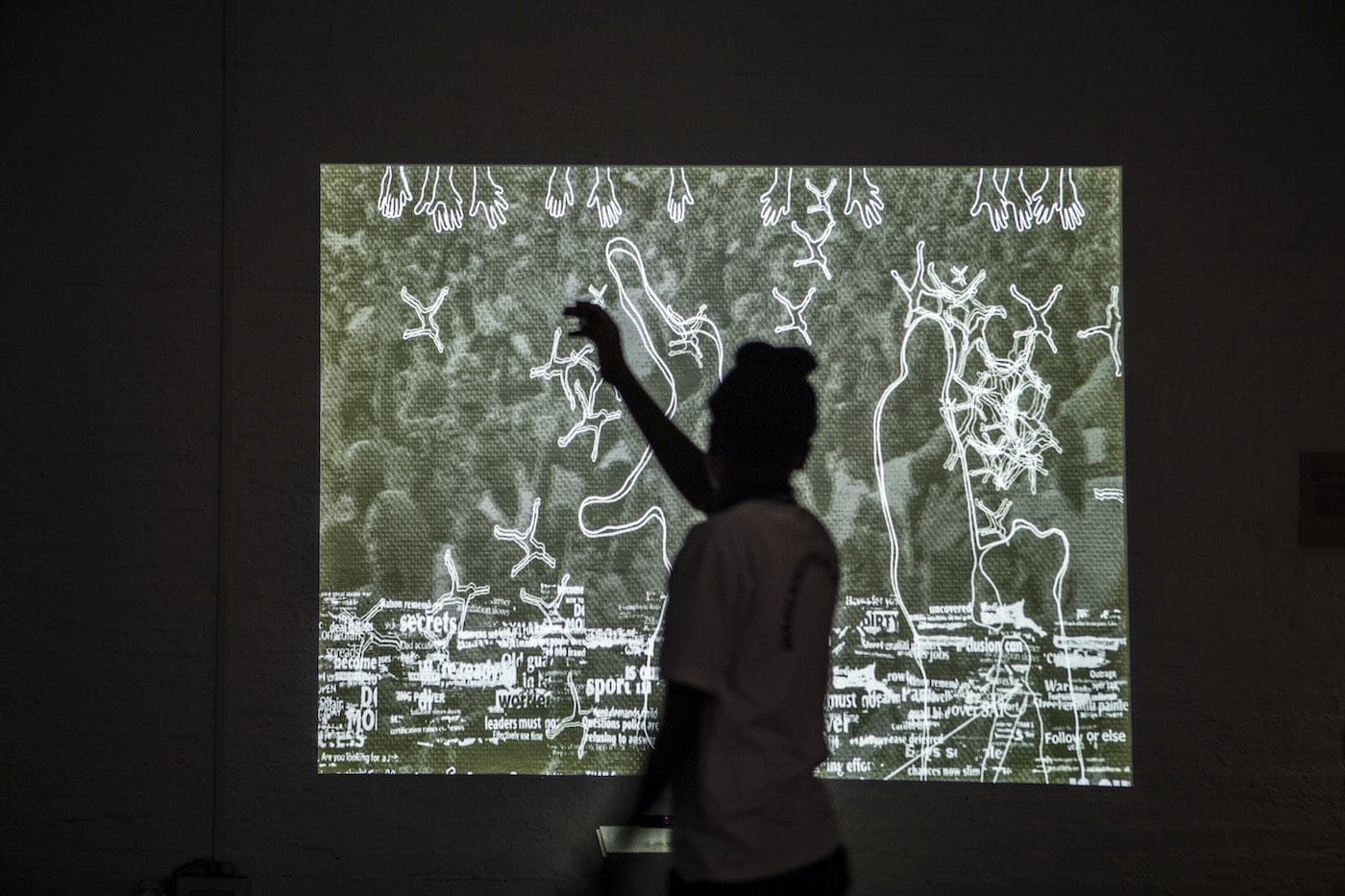

<figcaption> kate-hers RHEE, 7 Drawings, 28 Kisses, ©2013, performance, photo credit: Aleks Slota

C&: Another work of yours, which you produced in collaboration with Abbéy Odunlami, is the performance And then there were none. What is the point of this performance and where does the title come from?

khR: This work belongs to a series I made with Abbéy Odunlami from 2012 to 2014, in which I interpreted the former name of the German sweet, N-kuss, to be a cultural artifact, as a means to understand German culture. As I encountered white Germans still using the outdated and racist term colloquially, I was struck by how nonchalant they were, with absolutely no irony. However, because I never experienced anyone speaking this word in front of a Black person, it seemed as though there was something morally wrong about it, even if it wasn’t articulated.

I play the female character and Nigerian-American artist Abbéy Odunlami plays opposite me. We perform a strange sadistic ritual of giving and taking kisses. Abbéy ostensibly controls the entire scene, placing 10 Schokoküsse in my mouth as he brings his mouth to mine. His behavior gradually changes from slow and controlled to suddenly aggressive or passionate. That is up to the viewer to interpret. Above all, if we focus on the vulnerable confrontation between an Asian female and Black male, we notice the absence of a white character. Indeed this lack of whiteness is intentional and is only present when there is a potential white viewer.

Read more from

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Read more from

Flowing Affections: Laryssa Machada’s Sensitive Geographies

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?