The Congolese painter Djilatendo, who first exhibited in Brussels in 1929, is the subject of renewed attention in Europe. This recall is not without meditation or dilemma.

Thela Tendu aka Djilatendo, Untitled, ca. 1930 Watercolor and colored inks on paper Courtesy Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels Photo: Philipp Hänger

The exhibition Patterns for (Re)cognition at the Basel Kunsthalle, which ran from 13 February to 25 May 2015, was described as “the largest exhibition to date” of the work of Vincent Meessen, but also as the largest show yet of the abstract artwork of Djilatendo. If the exhibition leaflet spares no superlatives about its coverage of both artists, it still does not accord them the same status. On the one hand, there is Vincent Meessen, the rising Belgian artist who represented his country at the 56th Venice Biennale and, on the other, Djilatendo, an obscure Congolese artist who died in the late 1950s and whose work was dusted off from the archives of the Royal Library of Belgium, which had been unaware of its collection’s riches. The show is more than an homage to the Congolese artist. Inscribed in Meessen’s more recent approach, it allows us to reexamine modernity and its colonial baggage using the tools of Western critical thought. That last line ought to raise eyebrows. What response, exactly, is opened up by examining the problem of colonial denial once again in another time, another context, but always with Western conceptual tools?

The exhibition was built around watercolors by Djilatendo, who is seen as one of the forerunners of modern Congolese art, along with Albert Lubaki and lesser-known figures such as Massalai and Ngoma. Together, they formed the group known as the “illustrators of the Congo,” which Europe “discovered” in the late 1920s by way of Georges Thiry (a colonial officer in the Belgian Congo) and Gaston-Denys Périer (an official in the colonial administration in Belgium). From 1929 to 1936, they put on exhibitions in Geneva (Geneva Ethnography Museum), Brussels (the First National Salon of Negro Art and an exhibition of popular art at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts), Anvers, Rome (Exhibition of Colonial Art), and Paris. Their watercolors, inspired by the practice of painting on huts, were produced on Thiry’s orders and dispatched, without fail, to Europe. They only encountered qualified success upon arrival.

Djilatendo was a tailor living in Ibanc, a locality near the current city of Kananga, located in Lulua province at the center of the Democratic Republic of Congo. His work included paintings of figurative scenes illustrating his vision of modernity (cars, airplanes, characters in European dress carrying umbrellas, etc.), but also abstract watercolors. He illustrated the book L’éléphant qui marchait sur les œufs (The Elephant Who Walked on Eggs), the first publication of folktales transcribed by a Congolese author named Badibanga.

In Patterns for (Re)cognition, Vincent Meessen places Djilatendo’s abstract watercolors in dialogue with tests by André Ombredane, a French psychologist who introduced cognitive tests aimed at identifying the best “ethnicities” or choosing hired hands for colonial industry. The films were made by Robert Maistriaux, to whom Meessen pays fairly little regard, apart from the credits for the video on Ombredane’s Congo TAT test. Maistriaux wrote the treatise L’intelligence noire et son destin (Black Intelligence and Its Destiny), published in 1957—four years after the video shown at the exhibition—containing hard pronouncements about the intelligence of the groups subjected to the tests, especially those living “in the bush.” We read, for example, that:

“In essence, the black man’s early childhood takes place in an environment intellectually inferior to anything we can imagine in Europe.” (p. 191)

from left to right Thela Tendu aka Djilatendo, Untitled, ca. 1930 Watercolor and colored inks on paper

Courtesy Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels; Thela Tendu aka Djilatendo, Untitled, ca. 1930 Watercolor and colored inks on paper. Courtesy Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels; tshela-tenduo, Untitled, 1931 Watercolor and colored inks on paper. Courtesy Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels. Photo: Philipp Hänger

The tests, designed in part to measure the test-taker’s ability to respond to abstract shapes, were used to demonstrate these assertions. Vincent Meessen’s demonstration runs contrary to this pseudo-intellectual approach by referencing Djilatendo’s abstract work from 1920 to 1940. In an interview from 22 July 2015, Meessen explained:

“Seeing how this connection to intelligence was drawn, one cannot help connecting it to abstract art that was produced at the same time and had an incredible boom in Europe.”

Meessen is also interested in the transition from painting on huts to painting on paper and the introduction of the signature, which marks the birth of the artist as an individual and speaks to a production opening up to the art market. Djilatendo signed his work in many ways: ThselaTendu, tshelatendu, tshe latendu, Tshela tendu, Thelatedu, tshielatendu, thielatedo, Tshalo Ntende, and so on. Based on work by the German scholar Katherin Langenhol, Meessen counted a total of forty-two spellings of Djilatendo. He was likewise interested in the signature’s placement on the painting and notes that the artist attempts to repeat a motif until he reaches a transformative shape—which is where he signs his own name in one of its manifold spellings. Elsewhere in the same interview, Meesen said:

“He is ordered to ensure the artwork’s authenticity. It is my firm belief that he is making a conscious gesture, playing with the colonial criterion of fixity as a trait of the modern artist. And even if he did not do so consciously, the artist was at times foiling the alphabet, the tool of identification imposed on him, and the ensuing fixity. Thus he enabled himself to travel in his work.”

With the two iterations of the exhibition, Meessen changed the name of the artist with whom he was co-exhibiting. At the Kiosk in Gent, it was Tshiela Ntendu. At the Kunstalle in Basel, it is Thela Tendu. It seems to me that in renouncing the more or less established spelling of Djilatendo and in modifying the name in the exhibition’s publicity, he is diluting the artist’s identity when in fact the artist intended to multiply it.

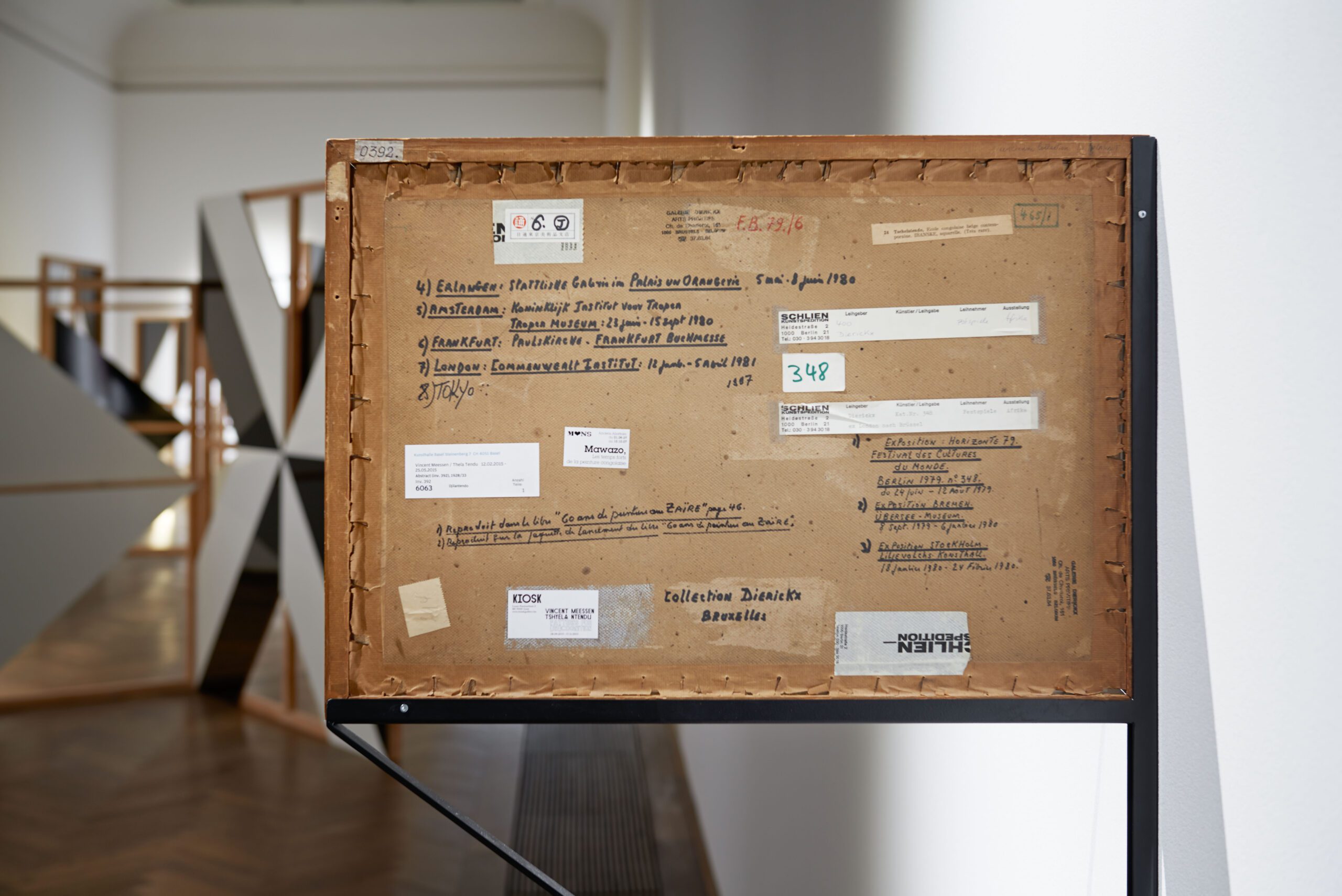

je Thsela te-ndu, Untitled, ca. 1928–33 (back side), Gouache on paper, steel display system. Courtesy Pierre Loos, Brussels. Photo: Philipp Hänger

In addition, the Swiss version of the exhibition, which distributes around thirty watercolors among five rooms, never entirely devotes the space to the expression of Djilatendo, who is invariably subjugated to other voices, all of them Western. The first room places them in dialogue with the films about Ombredane’s tests. The second highlights their commonalities with the paintings of Paul Klee and their Kuba identity. The third returns to Ombredane’s publications. The fourth is devoted to revisiting Jan Vansina, the patriarch of oral history who met Djilatendo in 1953. In the fifth room, Meessen opted to exhibit his own work, covering the entire floor and creating dialogue with the space. It is as if, in order to find its place in modernity, this Congolese voice needs Western “backing” or interpretation, endorsing its place in the hallowed halls.

I note with satisfaction the varying approach taken by the following project, Personnes et les autres (Persons and Others), presented at the Venice Biennale. There, Vincent Meessen shares an encounter with Joseph M’Belolo Ya M’Piku, a Congolese member of the Situationist International, and brings to life a text he composed in May 1968.

All of this reminds us of the great task that remains before us: to rewrite the history, the histories, of art or thought, according to the perspectives of colonized peoples. Meessen’s reminds us of the necessity of profound, ongoing work of rethinking, rewriting, and, to paraphrase V.Y. Mudimbe, Reprendre.

Patrick Mudekereza is a writer and cultural producer, living and working in Lubumbashi, DRC. He runs the Picha art center, and co-founded „Rencontres Picha“, the Biennale of Lubumbashi.

More Editorial