Michael Armitage: Painting From Afar

9 May 2019

Magazine C&

6 min read

Contemporary And: What was your first feeling about Venice? And what will be your contribution to the exhibition? Michael Armitage: When biennale curator Ralph Rugoff came to my studio to talk about his ideas, it was kind of uncanny. I had been working on this group of paintings for about a year. Initially they were …

Contemporary And: What was your first feeling about Venice? And what will be your contribution to the exhibition?

Michael Armitage: When biennale curator Ralph Rugoff came to my studio to talk about his ideas, it was kind of uncanny. I had been working on this group of paintings for about a year. Initially they were about power relations between a political leader and his followers, but then I went to the last major election rally of the opposition party in Nairobi in 2018. I just wanted to analyze the power dynamics at play, but when I got there it was such a grotesque and carnivalesque situation that other questions arose. Around 20,000 opposition supporters were dressed as clowns with orange heads, big glasses, and red noses. They were sitting in the trees of Uhuru Park in Nairobi, holding banners saying “you can’t kill us all” or showing Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper with the opposition leader floating above Jesus’s head. There was so much going on visually that I started to think about fanaticism and how similar politics and protest can look like around the world. I wondered why people put their lives on the line for political protest: Was it worth it? So Ralph’s concept and this year’s biennale title, “May You Live In Interesting Times,” felt like an uncanny kind of marrying up of his intention with my own work.

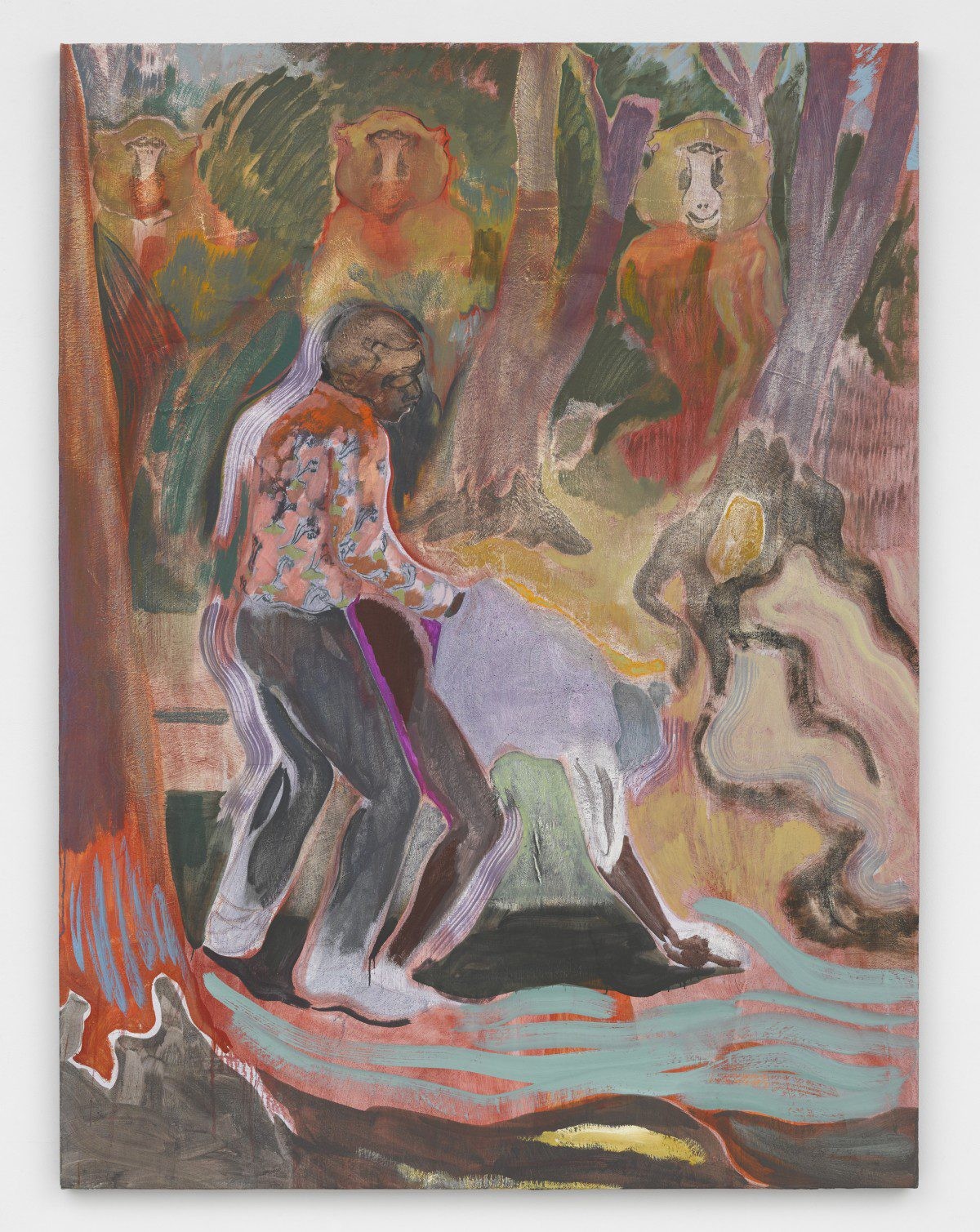

<figcaption> Michael Armitage, Muliro Gardens (baboons), 2016. Oil on Lubugo bark cloth © Michael Armitage. Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery.

C&: How does it feel to install these paintings in Venice, so far away from the protest ?

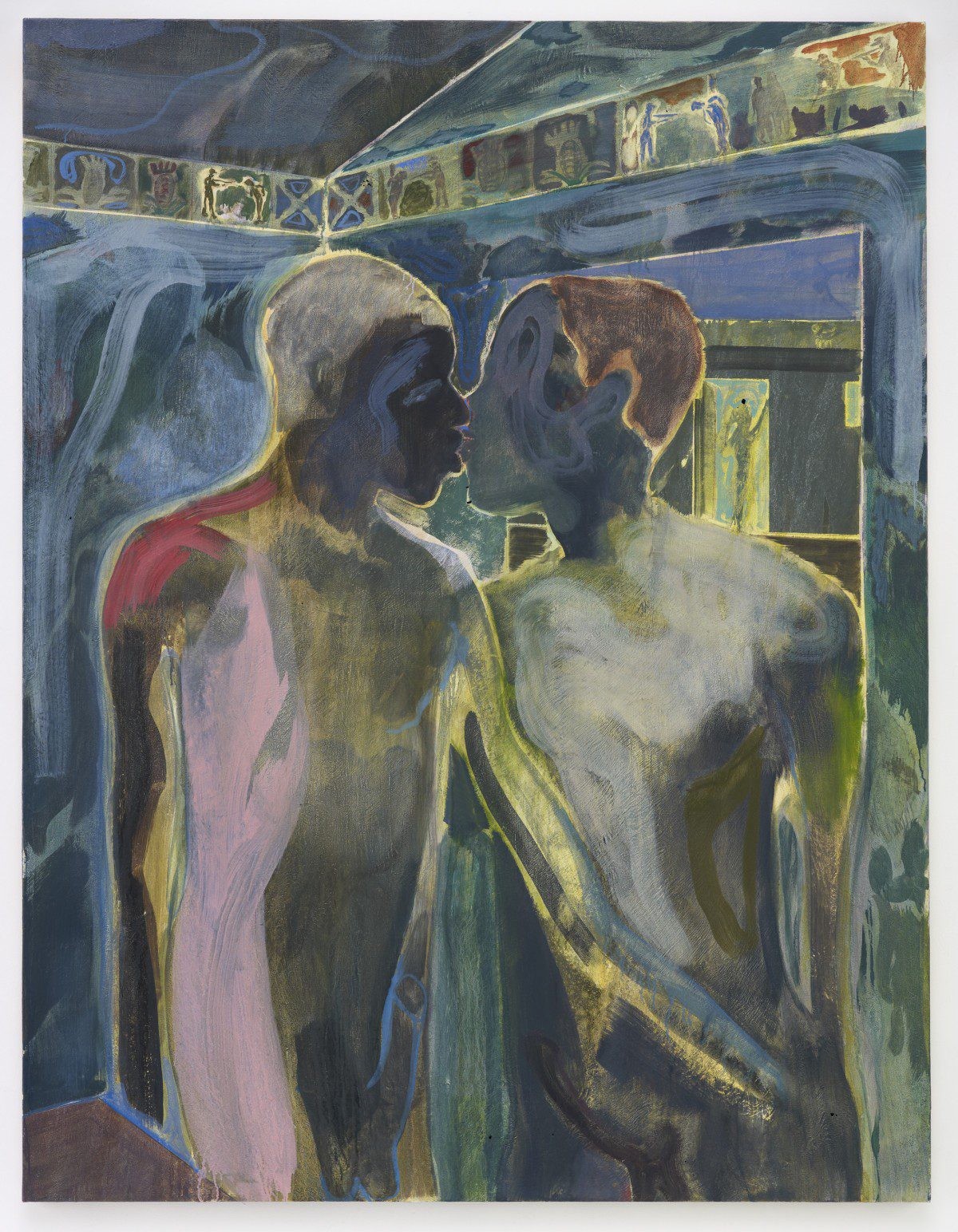

MA: I am really happy to be among this group of other artists and their work. My paintings are in the same space with the work of Julie Mehretu, who obviously in her own way also looks at the issue of protest. I have really enjoyed being with these very different yet similar bodies of work. Which in a way echoes my paintings about collective protest. Being removed from the actual situation is a familiar position for me since I’ve never exhibited in Kenya or East Africa, so far.

C&: In terms of crowds and collectivity – how do you think about the idea of a single curator creating such a big exhibition and the national pavilions?

MA: The variety in Venice comes from the national pavilions, and of course it has an element of nationalism. To me these controversial things about Venice are interesting because of all the problematic ideas around the single perspective, the national positions… Ralph’s idea of having two very different exhibitions with the same artists is really intriguing, for exactly those controversial reasons. Trying to expand the idea of a single, overarching voice by doubling it up brings his own voice into conversation with all these things and that is a super dominant and important position.

C&: Can you relate to the idea that the poetic moment in your work comes from the many stories and layers in it? Is it a strategy to avoid a single meaning?

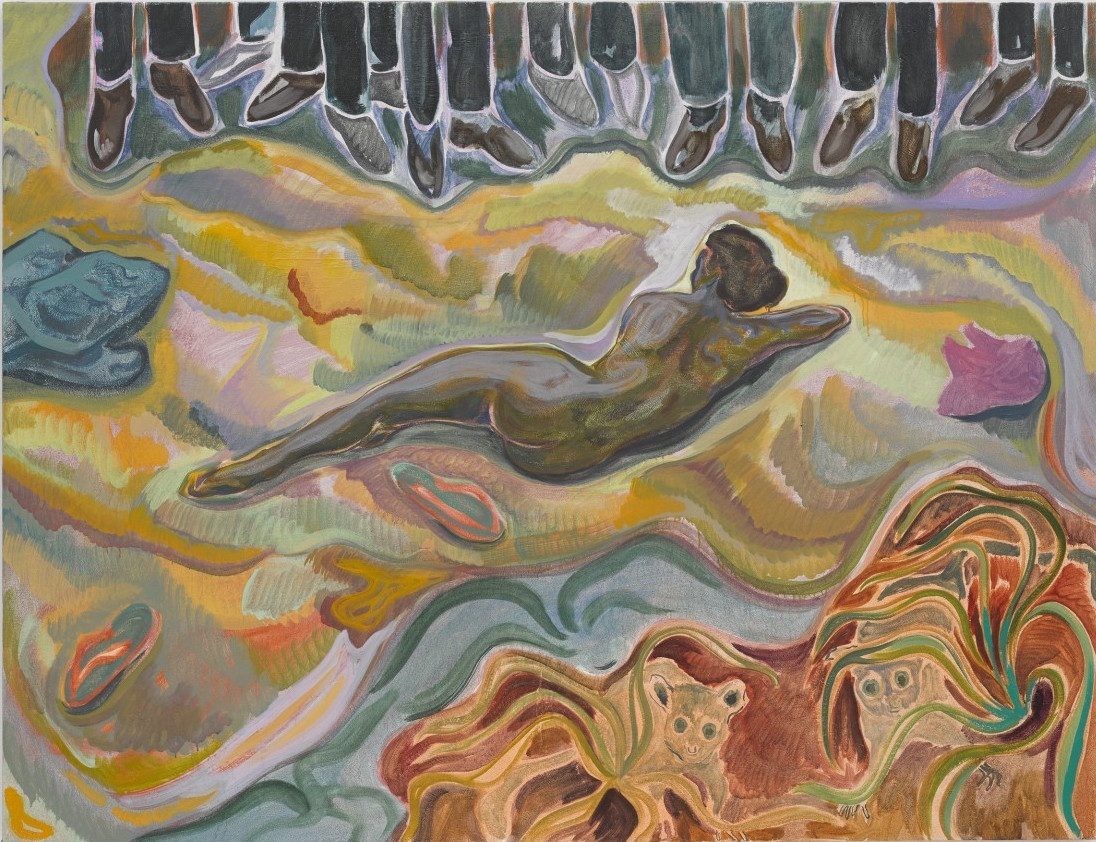

MA: I wouldn’t say “avoiding” a single meaning. I think it is important for the work to reflect a single situation and to realize that there never is a single perspective or meaning, even if it is your own. I think the poetic is implied in anything. There is this painting I made a few years ago called #Mydressmychoice. I had such a visceral reaction to the idea that anybody would strip and molest a woman because she wore a dress which in their eyes was too short. It was horrific. And the position of the woman, central to my painting, is taken from Velázquez’s Venus, making the reference to art history and an iconic image of beauty and the woman. So the situation and the subject provided the complexity by also referring to the secular dynamics between men and women that are responsible for so much violence.

<figcaption> Michael Armitage, Kampala Suburb, 2014. Oil on Lubugo bark cloth © Michael Armitage. Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery.

C&: Talking about subjects and their complexity, what is central to your work?

MA: I suppose what I am interested in is people, people under pretty exposed socio-political pressure or situations. And usually I need something which makes me feel conflicted. And that’s neither bad or good. In #Mydressmychoice it is obvious that it is a pretty horrible situation, that these violent attacks against women happen, but I suppose my conflict was to accept that this is an aspect of my own culture and therefore of myself.

C&: How does your work speak to each of the cultural environments in which you live and work?

MA: My subjects aren’t based in London at all, I just don’t feel affected by things that happen in England, even though I have been there for 20 years. When I see something I can see the anger and frustration, but I don’t feel personally affected in the same way I do in Kenya. But of course my art education and exposure to art, which has been influenced very much through a kind of limited British perspective, are essential to my approach to painting. And that is as fundamental as the subjects that I choose. I wouldn’t say that I work differently in one or the other context, but they certainly give me different things. Also because when I am in London, I only work. When I’m in Nairobi I am more outside and involved in life.

Aspects of my work are conceptually driven. I would have never chosen bark cloth to work on at home for example. I wouldn’t have felt the pressure to do so, as I did in London, where I was in a foreign context with my work and its subjects. So from the beginning it became really important for me to locate language, imagery, and material in East Africa. I don’t think I would be doing what I am doing now if I hadn’t been through that education and the frustration of never having shown my work in its natural habitat.

Michael Armitage is living and working between London and Nairobi. He paints with oil on Lubugo, a traditional bark cloth from Uganda, which is beaten over a period of days creating a natural material which when stretched taut has occasional holes and coarse indents. As noted by the artist, the use of Lubugo is at once an attempt to locate and destabilise the subject of his paintings.Interview by Theresa Sigmund.

from

In Conversation

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

‘To Treat Process with Care and Intention’: Favour Ritaro Carries Forward Important Curatorial Legacies

from

Painting

Rest in/as Freedom: kiarita and Black Politics of Liberation

Modupeola Fadugba Wins The Norval Sovereign African Art Prize 2025