Love is the Message

In his new single-channel video installation Love is the Message, the Message is Death at MoCA Geffen in LA, Arthur Jafa uses the Black gestural sign as a way to demonstrate his project of “black visual intonation.” Within the layered narrative of the piece, he juxtaposes older visuals with the new. The artist experiments with …

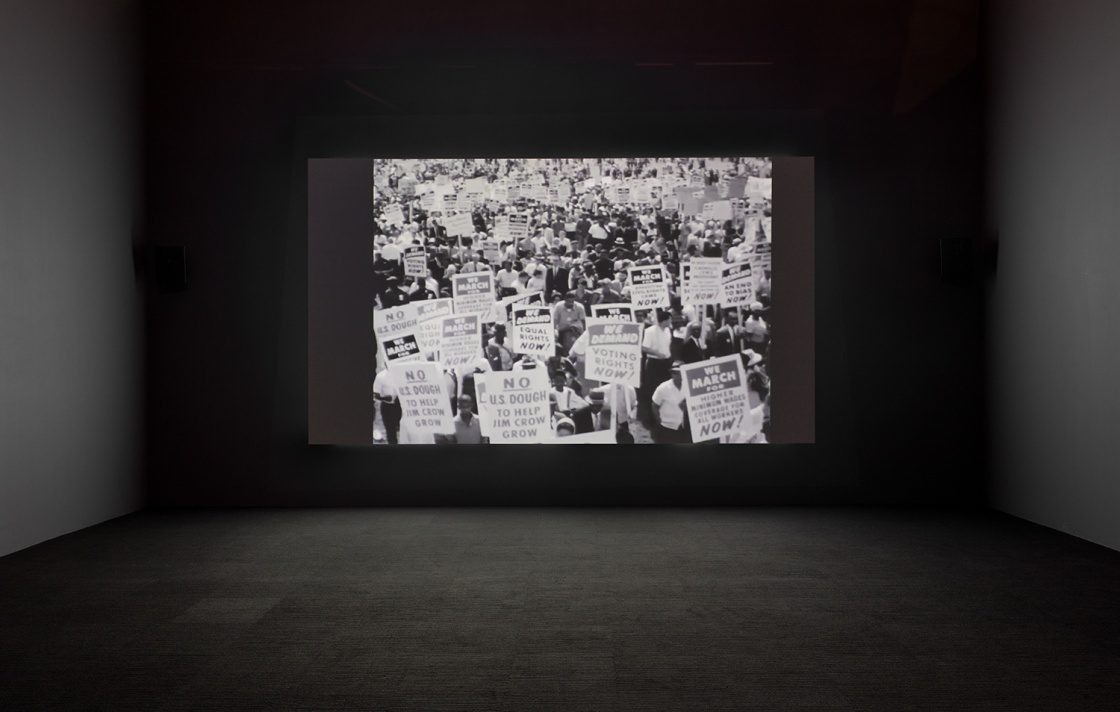

In his new single-channel video installation Love is the Message, the Message is Death at MoCA Geffen in LA, Arthur Jafa uses the Black gestural sign as a way to demonstrate his project of “black visual intonation.” Within the layered narrative of the piece, he juxtaposes older visuals with the new. The artist experiments with technology to demonstrate the different forms of Black cultural production that Black artists have played with to create new ways of mediating their Blackness. The images on show include bodies falling during a dance or police violence; dancers performing bodily inflection and rhapsodic inversion; The Notorious B.I.G. motioning whilst rapping as a teen; and rapid spiritual signaling in church. And all of these are in one way or another rooted in an historical rhythm incubated in West Africa – the then center of the transatlantic slave trade into the Americas. This staccato, or “stuttering,” that Jafa deploys in his rapid cut-ups and restless shuddering bodies, is the same one that artist Kameela Rasheed speaks of in the history of the subaltern.

<figcaption> Installation view of Arthur Jafa: Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, April 2–June 12, 2017 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest.

The video is an assemblage of YouTube clips and other found material. There is recent footage and a historical amalgam of dramatic, documentary and music videos. Jafa’s reading of music videos, YouTube videos, YouTube stars, and news clips as serious forms of artistic output is key to his concept of “black visual intonation.” By including these fractions of postmodern visual culture, Jafa is subverting the notion of high art and reversing the predominant model. The layering of these multi-dimensional narrative structures, or what Jafa refers to as “polyventiality,” is the foundation of a re-working of what constitutes Black cinema, which is not necessarily determined by the cultural producer’s heritage. Instead, it is what they produce and whether the material fits the distinctive patterns that Jafa questions in his essay 69: “How do we make black images vibrate in accordance with certain frequential values that exist in Black music?” This topic is also addressed throughout the work of Frances Bodomo, Kahlil Joseph and Melina Matsoukas.

<figcaption> Installation view of Arthur Jafa: Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, April 2–June 12, 2017 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest

Kanye West's Ultralight Beam is the perfect score. West’s musical assemblage, his refusal to fit into those specific American categories of Black, hip hop, urban and so on reveal someone seeking a new form of subjectivity. This quest for new forms of Black subjectivity is one that Jafa has been seeking through his cultural criticism, his archive and previous cinematic accomplishment Daughters of the Dust and, more recently, Solange's Cranes in the Sky and Don’t Touch my Hair. The layering of West’s tones, gospel singer Kelly Price and Kirk Franklin with Chance the Rapper’s expert storytelling help to keep the installation in a zone of optimism with the repeated chorus of “ultralight beam” and “this is a God dream.” Any other gospel or R’n’B song could have been used, but the insertion of West’s gospel-infused track into the installation sends a signal to the audience that this is a modern exploration of the Black presence in America. The strength in using West’s opening track from The Life of Pablo stems from the controversy the album courted because West kept editing it even after its initial streaming release, hence calling it a “living breathing changing creative expression.” And Jafa’s cinematic stuttering mirrors the musician’s syncopation here, displaying his curatorial genius.

Love is the Message is an extension of his earlier installation shown at LA’s Hammer Museum as part of their Made in LA exhibition in the summer of 2016. A series of still images collected by Jafa between 1990 and 2007, it is a display of his meticulous rendering of a Black aesthetic. And this is where he begins with this new work, sometimes presenting images in visual pairings through a series of repeated tropes.

Installation view of Arthur Jafa: Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, April 2–June 12, 2017 at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forres The video is extremely affecting, and it retains its harrowing impact even after multiple viewings. Part of this comes from the poignancy of the faces of those maligned and attacked by state-sanctioned violence, whether they are anonymous or famous faces. Another powerful aspect is stylistic details like the silencing of West’s sound track to make way for Obama’s rendition of Amazing Grace, or a clip of Martine Syms’ video on The Mundane Afrofuturists Manifesto and Earl Sweatshirt’s Hive, coupled with the climactic ending of James Brown’s sanctifying knee-drop. These are just some empirical examples of the brilliant yet lo-fi effects that make Jafa’s concept of Black cultural production so powerful and set him apart from the current defining paradigm. Arthur Jafa. Love is the Message, the Message is Death is on show at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, until June 2017. From June 8-Sept 10 2017 the Serpentine Gallery in London shows his new solo exhibition entitled:A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions. Nan Collymore is a writer and ponderer. Materiality and embodiment are central to her work. She writes, programs art events and makes brass ornaments in Berkeley California. Born in London, she has lived stateside since 2006

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission