In presenting a compelling interplay between reality, fiction and crisis, Lokko delivers a lesson on accountability for curatorial practices.

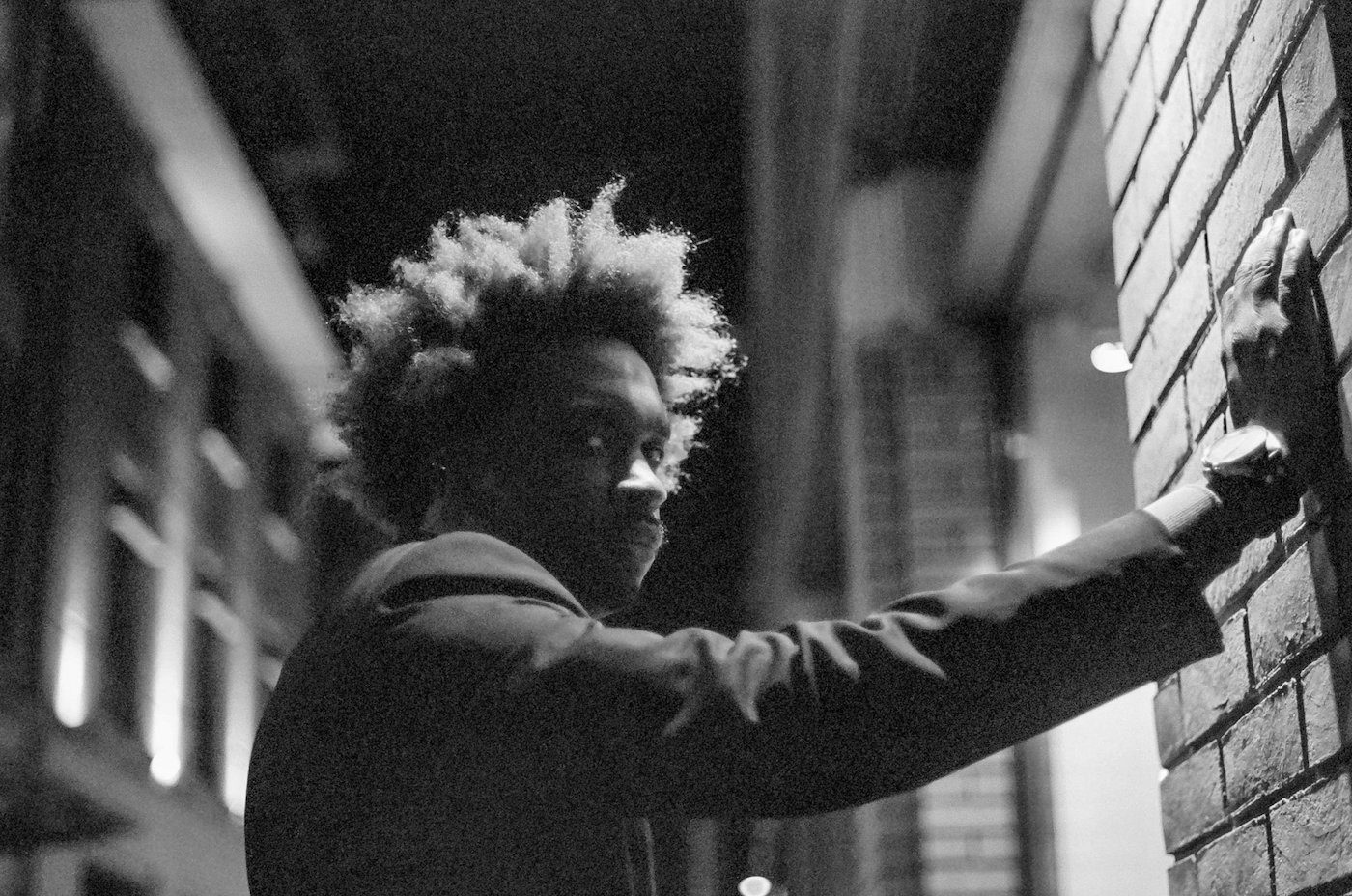

Rhael "LionHeart" Cape, Still from the film "Those with Walls for Windows", 2023

Lesley Lokko’s curatorial project for the 18th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice, The Laboratory of the Future, started as an idea she had for an experimental workshop. For this year’s biennial, the Ghanaian-Scottish architect, polyglot and bestselling author turns the Venetian model of gathering and accumulation into a series of moments and processes that carefully open a path toward dealing with the ruptures and changes of a world in crisis. In doing so, Lokko delivers a pivotal lesson on transparency and accountability for present curatorial practices.

It might feel premature to comment on the vastness of what this biennial might actually condense and echo for the next editions. But the work Lokko has been diligently carving out for the last thirty years definitely sets a tone. For me, the depth of that awareness and work manifests not as a conventional show but as the simplest, earliest and perhaps most symbolically loaded architectural type: a bridge. With that image in mind, I would like to attempt an overview of the many displayed views and forms that imply a real shift in curatorial practice. One that could lead global society towards more plurality, leaving behind the dependence on certain types of expertise, opening up to other experiences of the practice of building – especially in cities – and to buildings that uphold ideas of environmental justice.

Studio Sean Canty, Edgar’s Shed, 2023. (Sean Canty, Philadelphia USA 1987, lives and worKs in Boston. USA.) Technical collaborators: Hanif Kara OBE. Edoardo Tibuzzi (AKTII), Erich Gruber, Erich Bergmeister (LignoAlp). Team: Sarah Dunham, Jan Kwan, Gabriel Soomar, Justin Jiang, Austin Couch. Soundscape Designer: Darien Carr. With the additional support of Harvard Graduate School of Design. Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo.

The biennial as a bridge as a déjà vu

By basing the structure of her show on what remains from the art biennial that Cecilia Alemani curated in 2022, and just making minimal changes to the rooms for site-specific interventions, she makes a sophisticated statement on a sustainable use of resources. This statement gains in depth through two main chapters – Force Majeure (on the diasporic in all its dimensions) and Dangerous Liaisons (on resisting architectural purity) – as well as through four sections for transdisciplinary projects that prioritize practitioners rather than academic experts: Food, Agriculture & Climate Change, Gender & Geography, Mnemonic and Guest from the Future.

Most striking is the gentle ways in which the historical whiteness of the biennale is treated, by placing the portraits of the practitioners nextevery exhibit, and insisting that a majority of PoC and Black People is really a novum. Thus I see it, what Lokko is telling us, with wide open eyes: imaginative ideas about the future are only graspable not by building buildings, but by visibilizing the work of people, and how they hold these ideas through friendship, how they live this deep knowledge.

Poet and architect Rhael “LionHeart” Cape appears on a large screen that merges images and words in Those With Walls for Windows (2023), flashing through calls for action on current housing, displacement and migration crises among quotes from Audre Lorde and James Baldwin. The film is placed just before the contribution from Nine Studio and Sammy Baloji, titled Aequare: the Future that Never Was. The quotes, the poems and the films intertwine the path for visitors to start looking for connections beyond the standard parcour of the exhibition display in the former artillery reservoir of Venice.

Rhael “LionHeart” Cape, “Those With Walls for Windows,” 18th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice Biennale, The Laboratory of the Future. Photo: Marco Zorzanello. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

Both Those With Walls for Windows and Aequare are pieces that collage film footage to make contemporary struggles legible. LionHeart boldly refers to Black People’s struggles across centuries. Baloji takes archival materials from Belgian Congo with images of his own that were created as part of his recent field research on the dematerialization of the landscape and the delocalization of pre-colonial social systems through colonial action. LionHeart and Baloji are only two of eighty-nine participants from Africa and the African diasporic communities around the world that have turned the focus of the biennial into the display of massive asymmetries in representation and worldbuilding.

The biennial preparations were not exempt from exclusivism, manifested as structural racism, as the denial of visas to Ghanaian curators for entering Italy was already a political mark left by the right-wing conservative government that hosts the exhibition. But because architecture is a relationship, not a thing, The Laboratory of the Future turns against the present ubiquitous sense of territory, property and access, against the uncontrollable growth of commodification, by focusing on what architecture can look like otherwise.

The bridge as an archetype into and out of property

What is architecture here, if the focus lies in methods of anti-building? The answer is in how materiality is displayed. The German pavilion is the clearest example: the curators – Krag and Juliane Greb (Büro Juliane Greb), Anne Femmer and Florian Summa (Leipzig-based practice Summacumfemmer), Franziska Gödicke, Christian Hiller, Melissa Makele and Anh-Linh Ngo (ARCH+) – of Open for Maintenance filled the fascist-era building with the remnants of last year’s art biennial, creating a space for care, repair and maintenance – a surprisingly warming space with care facilities. Hosting leftover materials from over forty national pavilions and exhibitions from 2022, the pavilion is a productive infrastructure, promoting principles of reuse and circular construction. Anyone can enter and acquire something made at the workshop on the side wings. The best part: at the end of the exhibition period, the pavilion is planned to be emptied out by its visitors, who can build furniture, sew tote bags and join any kind of workshop in the wings of the pavilion.

The German Pavilion as a material repository. Open for Maintenance. curated by ARCH + | @archplusnet, SUMMACUMFEMMER, Büro Juliane Greb; Curatorial team: Anne Femmer, Franziska Gödicke, Juliane Greb, Christian Hiller, Peter Krag, Melissa Makele, Anh-Linh Ngo, Florian Summa, commissioned by the Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building. Photo: Courtesy of Bureau N.

New vocabularies and actions for the meaning of building come to life through such approaches. Lokko had just inaugurated the African Futures Institute, the architecture school she founded in Accra, when she got the Venice appointment in 2021. So the institute and the biennial are very close to one another, with shared conversations, and principled beliefs around providing community.

Among the builders of kinships is Sean Canty and his studio, who present an installation based on two vernacular buildings Canty’s great-grandfather Edgar constructed in South Carolina in the US. Both were places of belonging and struggle, of smoke and joy, rhythm and blues. The work’s symbolically over-scaled roof represents the first act of sheltering; its tectonics are carefully accounted for and easily demountable for reuse.

The idea of the future is an important political space for Lokko, who measures her ambitions concerning internationalist ambitions against the global success of African and African diasporic movements from the past. To talk of Africa only as a place in the biennial context would be a fallacy; decoloniality and decarbonization are broad categories that demand specific interest in social phenomena, that refuse to reduce the question of architecture to one of dynamics of an exploitative market.

At the workshop, left wing of the exhibition project Open for Maintenance, with Anh-Linh Ngo, who curated this year’s German Pavilion, together with Krag and Juliane Greb (Büro Juliane Greb), Anne Femmer and Florian Summa (Leipzig-based practice Summacumfemmer), Franziska Gödicke, Christian Hiller, Melissa Makele and ARCH+. Photo: María Inés Plaza Lazo.

The bridge between reality and fiction

Until now, the biennial has been decidedly Eurocentric, with some contributions from the Americas and Southeast Asia. To repair what has been lost and done to the African continent’s ecoregion by former colonial powers, Olalekan Jeyifous’s ACE/APP (standing for “African Conservation Effort” and “All-Africa Protoport”) appears at the heart of the main pavilion as the ideal decolonized port, suggesting a sprawling network of low-impact, zero-emissions travel complexes situated off the coasts of major ports throughout the world. Imagine you could transport yourself through this most futuristic spaceship to the cities of Lagos, Mombasa, Port Said, Dar es Salaam, Durban, Salvador de Bahia, New York, Los Angeles, Port-Au-Prince, Barranquilla, Havana or Montego Bay. The representation of the Barotse Floodplain in AAP’s imaginary lounge is one of the most symbolic projects at the main exhibition, applying Indigenous knowledge systems to envision advanced networks that synthesize renewable energy and green technologies. It feels like Wakanda in there, reminding me of a conversation Lokko had with the Guardian before the biennial opened. She said she was impressed by “the way some of her South African students responded to the fictional city of towers and pinnacles in the Black Panther movies” – the depiction of an ideal city, untouched by the exploitation the whole continent has suffered – with floods of tears.

Like Wakanda, the biennial is a story told by human voices shared with non-human agents, mourning a loss, celebrating empowerment, and acting against extractivism. In the Uruguayan pavilion the film En Opera: Future Scenarios of a Young Forest Law, by MAPA+INST and Carlos Casacuberta, stages a scenario with Afro-Uruguayan musicians – it sings to us in an attempt to understand what is going on around forest law and why it does not receive the same attention as other regulations. Less playful but just as poetic is the Golden-Lion-winning Brazilian pavilion: Gabriela de Matos and Paulo Tavares, its curators, filled it with earth, and chose to focus on how Brazil’s land has shaped understandings of heritage and identity, encompassing the idealized and racialized vision of “tropical nature” that has shaped the portrayal of Brazil’s national identity. The pavilion is a truthful representation of ancestral connection beyond the borders of a country, letting everyone pass through it to feel the presence of the earth and forget, even if only briefly, the predominant cartographical understanding of it. TERRA gives alternative perspectives on belonging, cultivation, rights and reparation.

“The Black body was Europe’s first unit of energy,” Lokko told the Associated Press. “From my perspective, this relationship between the colony and carbon is linked in the body.” This powerful statement insists on seriously thinking about our role in the endless processes of decarbonization and decolonization. In a place like Venice, decolonization is catalytic, slow, and not just about an end product, but as understanding how people arise and consolidate commonality with themselves and the planet. Making this core of architecture transparent is thus to reveal a transformation that starts, again and again, with ourselves.

The Laboratory of the Future runs until 26 November.

María Inés Plaza Lazo is a founder and publisher of Arts of the Working Class, the multilingual street newspaper for art and society, wealth and poverty from Berlin. She just started working at the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden on communications strategies for the institution, at the intersection between curating, publishing and public relations.

More Editorial