The opening of the Black Cultural Archives’ purpose-built space in Brixton, London coincides with the arrival of Black Artists in British Art: A History from 1950 to the Present by Eddie Chambers – a book we have all been waiting for, says Hansi Momodu-Gordon

Community rally in support of Black Cultural Archives, 1984, London, UK (courtesy of BCA)

The opening of the Black Cultural Archives‘ space and Eddie Chambers’s new book focusing on Black artists in British art since 1950 are to significantly alter the terrain by marking out spaces for dedicated narratives for Black British artists in the history of art in Britain.

Central to Black Artist’s in British Art is the narrative of the persistent invisiblizing of Black artists in Britain on a continuum that charts the level of the art world’s openness alongside Britain’s immigration policy and the fluctuating temperature of race relations from the 1950s to today. What an organization such as the BCA invites, with its collection of ephemera, written and oral histories, photographs, and texts, is a way to look back at that history and access remnants of the very exhibitions, artists, and institutions that Chambers pinpoints in his text.

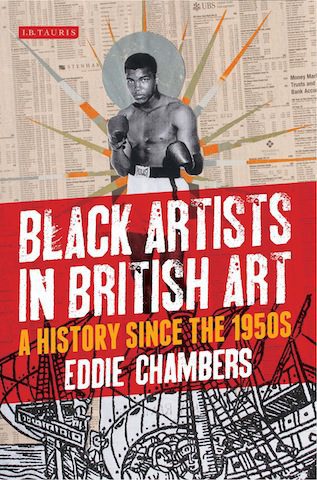

Eddie Chambers, Black Artists in British Art: A History since the 1950s, London, 2014

In the introduction, Chambers talks of a fall into oblivion for a great number of artists. He posits that even though each chapter in the book is centered on a group of artists working within a specific decade or particular moment, they all present a meta-narrative of “problems and progress.” Making this point again in the epilogue, the section focusing on contemporary practitioners, Chambers elaborates, declaring, “The history of Black artists in Britain reflects a steady and often predictable pattern, in which the fortunes of individual artists undulate, whilst the majority of practitioners have to settle for either fleeting visibility, or no visibility at all” (Chambers 2014, p. 195). Coupled with a chronic case of invisibility is the symptom of amnesia.

Not only have Black British artists throughout history been accorded relatively few moments of visibility, those occurrences have a tendency to be systematically forgotten about. Or rather, they have not entered into the national memory in a way that can inform subsequent generationst. One of the side effects of amnesia, aside from the loss of a significant history, is for certain artists to be continuously cast as a discovery, novelty, or fashion. Those declaring, in 2014, the discovery of art from Africa may have thought twice were they aware of the exhibition Contemporary African Art, held in 1969 at Camden Art Centre in London. Which is why the significance of Chambers’ careful research and notation of the exhibition history of Black artists in Britain cannot be overstated.

The Black Cultural Archives, Brixton © Edmund Sumner

Similarly, an engagement with history is reason to mark this new phase in the life of the Black Cultural Archives. The space is now located on Windrush Square, Brixton in an area of London that has been the epicenter of African and Caribbean migration to Britain throughout the 20th century and into the 21st and has been stage and set to many of the events that have shaped its history. In a conversation with Kimberley Keith, BCA Trustee, I was struck by a sentiment she expressed, closely echoing Chambers. Narrating the BCA’s history, Keith noted its move from “protest to progress,” as the organization sprung out of the protests and responses to the Brixton uprising of 1981 and has progressed towards professionalization, becoming both archive and heritage center. In both cases the telling of Black British (art) history is characterized by episodes of discord and progress.

The archive offers a powerful resource to artists, art historians, and curators as it is the evidence of our history, the history of artists from former British colonies – the Caribbean, Africa, South Asia – and of subsequent generations of Black British artists. Imagine my excitement to find in the BCA an original exhibition brochure from Caribbean Artists in England at the Commonwealth Art Gallery, Friday 22 January–Sunday 14 February 1971, with a list of 16 exhibiting artists including Winston Branch, Donald Locke, Ronald Moody, and Aubrey Williams, complete with black-and-white illustrations of their work. Picked out by Chambers for offering a high-profile opportunity for Caribbean artists based in London to exhibit, knowledge of this exhibition history is essential in informing our perception of an increasingly global art world and the place of Black British artists within it (Chambers 2014, p. 56). The Black Cultural Archives has the potential to be of central importance to the history of art in Britain, so long as they develop acquisition strategies that recognize the valuable contributions of Black British artists and continue to collect key source materials. As it is only when we know how far we’ve come that we can understand if progress really has been made. Here’s to progress.

Hansi Momodu-Gordon is a curator, writer, and cultural producer. She is Assistant Curator at the Tate Modern where she works on exhibitions, commissions, and collection research.

More Editorial