C& talks to Harare-based artist Gareth Nyandoro about local markets as his main source of inspiration and his unique “kucheka cheka” technique

Gareth Nyandoro, Installation view at Rijksacademie Opening, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

C&: Tell us a bit about your artistic journey. When did it all start?

Gareth Nyandoro: It started when I was still a young boy and made all sorts of objects with anything I could lay my hands on – metal, used wire, clay, etc. – and people appreciated these objects. So from an early age I was encouraged to pursue art and after high school, I enrolled for my first art qualification and went on to attain my first degree in printmaking and painting at Harare Polytechnic College. While I was studying, I participated in various exhibitions. It was a time when I explored and experimented with different mediums. I started off with found objects for sculpture and installations. At that time, it was influenced by the economic situation in our country, as we could not easily access “conventional art materials”; hence my paintings were more sculptural and three-dimensional rather than in conventional painting formats. But on a positive note, it’s through the use of these found objects that I made a mark on the local art scene. As my work evolved, I moved from found objects and started experimenting with paper and realized there was more I could with it. In 2014, I enrolled at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, and that was when I started working more with paper incisions and paper cutting.

Gareth Nyandoro, Pfuuuuuuuuu (Blowing), 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

C&: You had your first solo show called Paper Cut at Tiwani Contemporary this year. Why are local markets your main source of inspiration?

GN: I have always been fascinated with how vendors occupy, display, and arrange their wares in public spaces. They create colorful collages. In a way they have created a sketch for me, which I transfer to paper collages. When I was growing up, vending was there but in a conservative way. Now it has turned out to be an art among the vendors as they compete for space and visibility through creative displays and even go to the extent of using megaphones and dance to lure customers. These are all elements being used in the contemporary art scene, like performance and sound art.

Gareth Nyandoro, Kuguruguda Stambo (Hypnotic Lollipop Eaters) Mixed media on paper, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

C&: It is interesting that in your work, you break out of two-dimensional framing. Why?

GN: Breaking out of the two-dimensional frame gives my work more depth and emphasizes the idea I am putting across. In most cases, I use both two- and three-dimensional elements. I always try and think outside the box, so I feel that if I leave the work in two dimensions, it won’t be complete.

C&: Tell us a bit about the unique “kucheka cheka” technique that you have developed.

GN: As I mentioned earlier, I developed this technique from printmaking. I was improvising with cardboard for printing, rather than etching on linoleum board or woodblock. I realized that the surface I used for printing was actually a finished piece of work, which is when I started to engrave different kinds of paper. I make incisions on the paper and then sponge ink onto it; finally, I peel off certain areas leaving a kind of etching effect. I am still developing the technique and it has so many possibilities that I have yet to explore.

C&: How would you define Harare’s artistic contemporary scene?

GN: I would say Harare is booming with creativity. One can only come and see the abundance of new voices working for themselves.

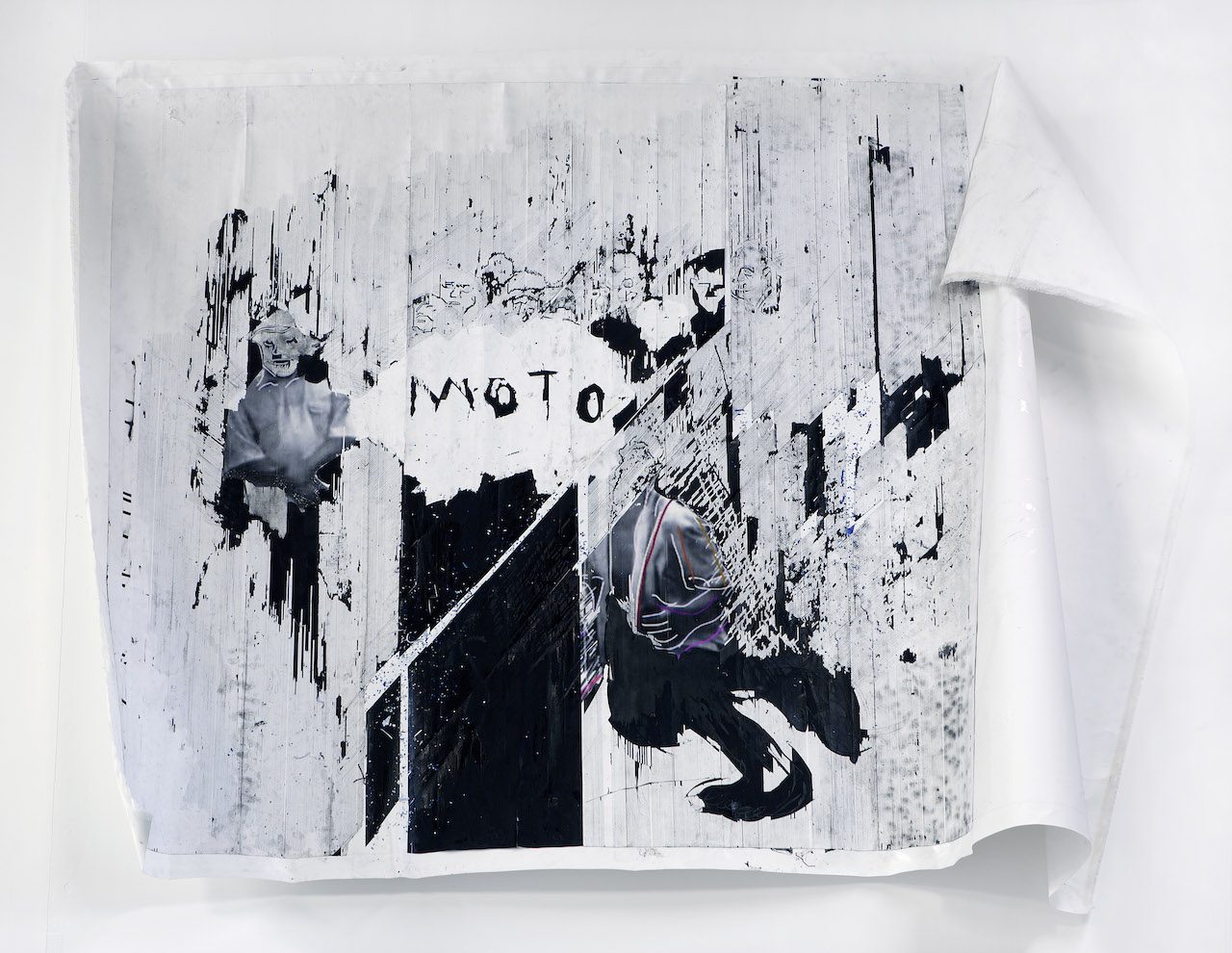

Gareth Nyandoro, Installation view at Rijksakademie opening, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

C&: With Misheck Masamvu and Georgina Maxim, you have set up the open art studio Village Unhu. What is the idea behind this project?

GN: This is a collective project in which we work with established and emerging artists with the aim of artists realizing, developing, and exchanging ideas. In addition to artist studio spaces, as Village Unhu we organize exhibitions, residencies, and talks. We are there to facilitate these activities for artists and especially those who are still emerging.

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

More Editorial