Ethel-Ruth Tawe talks to the author of The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women about photo archives, the female gaze, and male studio traditions.

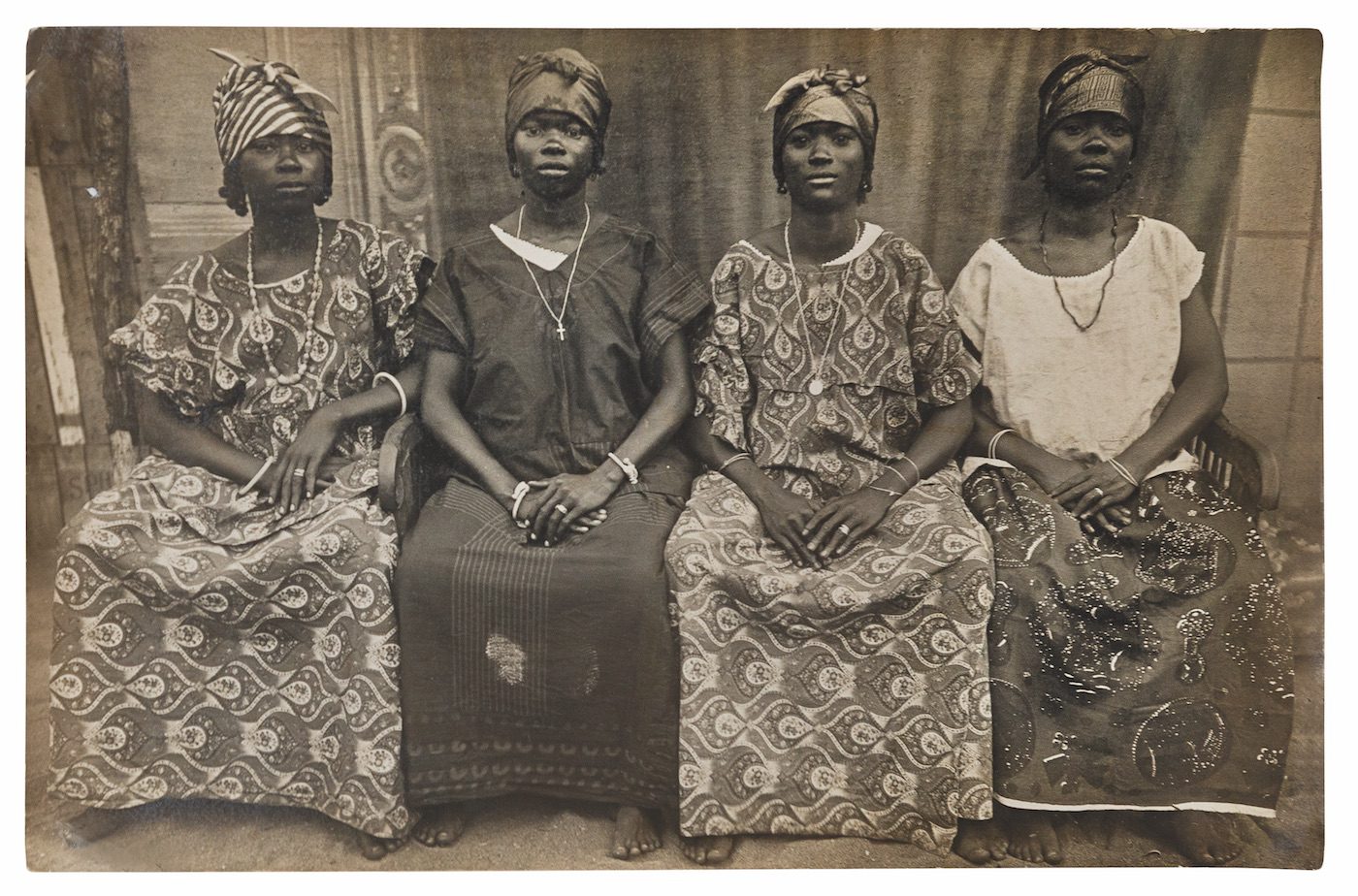

Baule Women, 1928, Unknown, Cote d’Ivoire. Courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook

Historically, when it comes to gaze and authorship in the context of photography, African women’s contributions have been gravely sidelined. But recently our perceptions of what shapes image-making processes has been expanded by artists and archivists alike. In conversation with Contemporary And, acclaimed author Catherine E. McKinley sheds light on the erasure and resilience of African women image-makers. The African Lookbook (2021) reads like a collective photo album with critical captions accompanying a trove of rare archival, vintage, vernacular, and contemporary images. McKinley draws attention to power dynamics, consent, subversion, and identity, examining the lives of African women “in the pursuit of modernity and resistance to colonialism and gender violence.” She unearths and dissects the grave imbalances that have long plagued African visual archives.

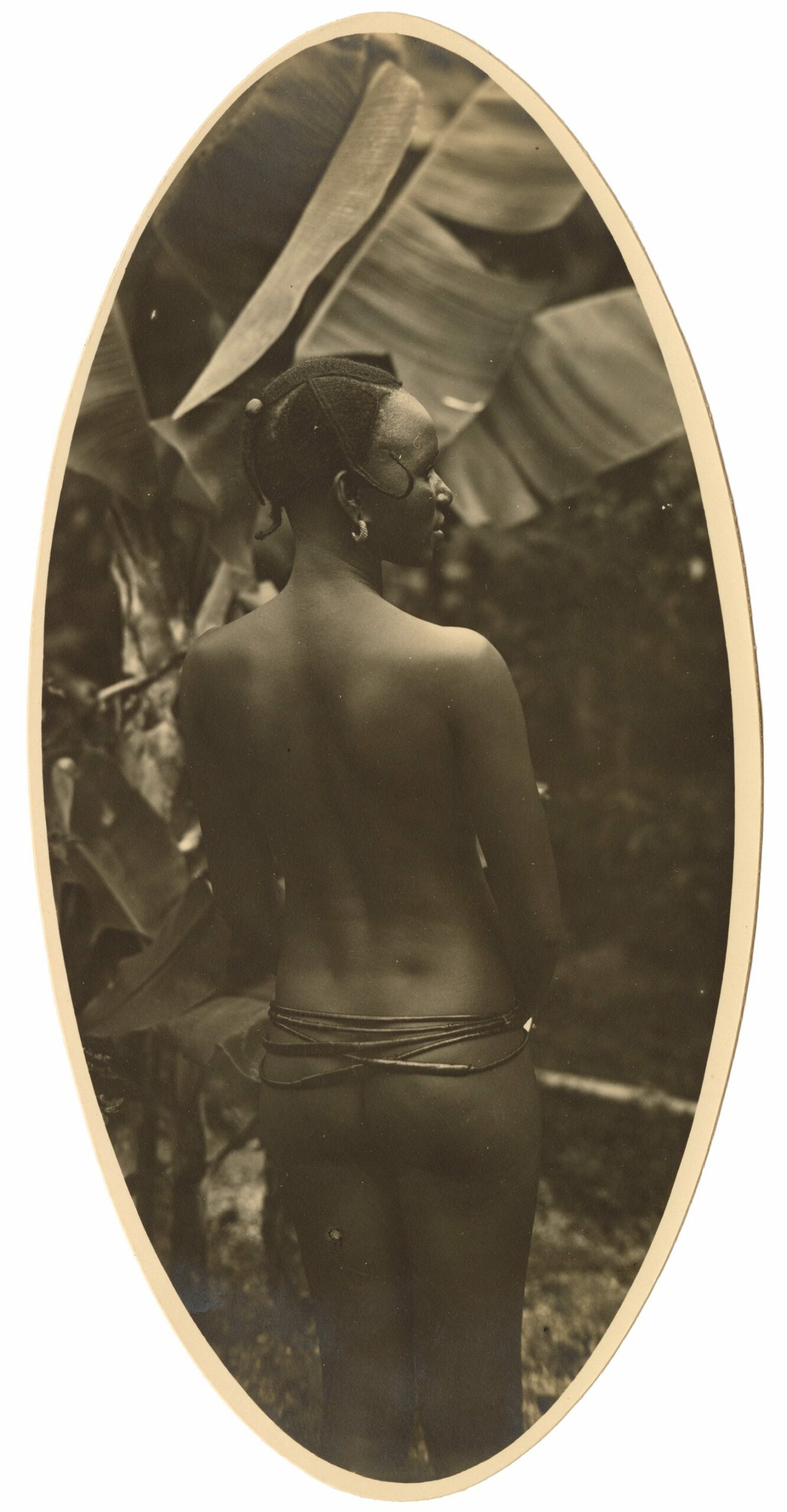

Untitled, c. 1930, Unknown Photographer from the Collection of Aladji Adama Sylla, Saint-Louis, Senegal. Courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook

C&: Why do you think a knowledge gap about African women photographers exists? And what are its ramifications?

Catherine McKinley: It is really important that we establish a clear and full art-historical record, especially since a disproportionate amount of the archive’s contents is preoccupied with the female body. Recently Ghanaian photographer Felicia Abban received honors as a “first.” There is such an utter absence of records of her foremothers and contemporaries that the claim is very passively accepted. But since she didn’t claim to be an artist in the way we speak of James Barnor or their contemporaries, where does she sit in relation to the gendered notion of the artist? And to the fact that there is historical evidence of women studio owners like Carrie Lumpkin from Nigeria, who were merchants and may not actually have taken up the camera themselves?

Peuhl Woman from Niger, 1970, Malick Sidibe, Mali. Courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook

Often, looking at the work of contemporary African women photographers, I have felt that they have benefitted from not emerging so consciously from the male studio tradition. I’m thinking of Patricia Coffie, Zina Saro-Wiwa, Zanele Muholi, Fatima Tuggar, Fatoumata Diabaté, and Ruth Ossai. Even with portraiture, their work is playful and inventive, groundbreaking in terms of form and content, and future-seeking – whereas many male photographers still seem bound to the past and to some of its rigidities.

Untitled, 1939-45, Unknown Photographer from the Collection of Aladji Adama Sylla, Saint-Louis, Senegal. Courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook

C&: How does your new book trace histories of the camera in Africa, and the relationship between photographers and sitters?

CM: Soon after the camera arrived on the continent around 1863, African entrepreneurs and descendants of captive persons from Brazil and the Americas took up the trade, many working itinerantly along coastal trade routes as far apart as Senegal and Angola, and into the Sahel. The book explores the politics of the studio, from the ways in which photography was meant to wound and control, to the grander, more playful, honorific role that studio visits played in the lives of African women sitters.

As we do not know the exact year that African women began to wield the camera; we only know of the few women that I’ve mentioned. We know that a critical mass of African women artists was only recognized in the late 1990s. So when we examine these photos, we must also examine the power relationships between photographer and sitter in African and Diaspora-owned studios.

Our Elegants of Djenne, Undated, H. Danel, Kayes, Mali. Courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook

C&: You state that the collection in your book is largely of the Sahel region, and what many refer to as the African-Atlantic. Why do you think so many of the early records are centered in Western Africa?

CM: In my thinking, early European contact in West Africa follows early colonial trade histories, so it follows suit that the technology took a lead there. Senegal is one of the earliest sites hence an amazing proliferation of studios there. Early African photographers seem to have arrived in Dakar and St. Louis via Guinea and Sierra Leone, but I’m not clear on the why. They were somewhat itinerant, or semi-nomadic, but the truth is, we do not know enough about any of this history.

C&: In the introduction to your book it says: “I have gathered these images, not just for me, but for you, also for them, who have reframed and reclaimed the camera as their own.” Can you expand on this? Why did you choose to call it a “lookbook”?

CM: I chose “lookbook” for several reasons. For the obvious fashion reference, and to play on the kind of Western master narrative of presenting fashion. African fashion does not comply because it largely doesn’t obey the idea of fashion being just about “a look.”

As a kid, I loved to dress and was “extra” in relation to a very sartorially conservative world. My mother was defiant of gender norms and thought clothing should be well-made and utilitarian above anything. The summer that I began high school, I ran away from town to Boston and spent all of my clothes money on some red pointy snakeskin shoes and a red, pink, and blue oversized mohair sweater. I never saw another dime for clothing for most of that year and so I wore them like a uniform. My mother lectured me endlessly about frugality and “substance” – about making meaning of things vs. being “a flower.” I think that explains why African fashion as a means to understand history took such hold for me. Both ideas are deeply inscribed in it.

Untitled, 1920, Unknown, Guinea, The McKinley Collection. Courtesy of The McKinley Collection and The African Lookbook

Then, over the years I’ve had friends – particularly other artists – question my “practice” because I spent my time in the market and tailor shops, in older aunties’ rooms, and at any possible “customary” occasion. I may have seemed to be shopping and socializing but I was doing primary research – a lost practice. So the book is a bit of a tribute to the aunties, the seamstresses, and traders, to my mother, whose insistence I do appreciate today, and to my comrades.

Ethel-Ruth Tawe (b.1994, Yaoundé, Cameroon) is a multidisciplinary artist and editor exploring African identity and diaspora cultures through visual storytelling. Cyclical conceptions of time are central to her practice which examines Africa’s ancient futures from a magical realist lens. Image-making, storytelling, and time-travelling compose the framework of her inquiry. Ethel holds an MSc in Development Studies from SOAS University of London and a BA (Hons) in International Human Rights with a minor in Art History & Criticism.

Read the full list of female image makers HERE.

More Editorial