These maps by Philippe Rekacewicz, published here on C& every day over the next couple of days, show how the phenomenon of migration relates to the issue of political borders.

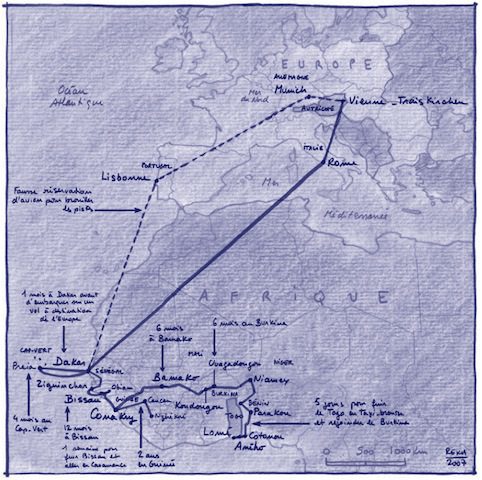

Gabriel's story © Philippe Rekacewicz

These maps by Philippe Rekacewicz show how the phenomenon of migration relates to the issue of political borders. They are not “finalized” maps, but rather rough drafts whose the provisional character attests to the nature of the border itself: ambivalent and paradoxical (it divides as much as it unites). Borders are difficult to map out: first the maps respond to the question of “where” and then they permit us to understand “what”, to understand how human communities organize and produce their territory to the detriment of their neighbors.

Behind every map, there is an intention. A map is born of an idea; it is an intellectual construction before being formalized into the sketched draft, the sign of that first cartographic intent. Once they are printed, the political maps of the world “ those depicting the complex networks of lines that symbolize borders – create the illusion of a world that is perfectly carved up into units of life, into regions and countries. They have an air of harmony about them, and they give the borders a sense of permanence. However, borders are inscribed into the landscape in a myriad of ways: they can tower up as thick, insurmountable barriers, or they can be practically nonexistent. Between these extremes, there is an infinite number of variations. And these virtual lines shift in time and space whenever history unsettles the world.

GABRIEL

Gabriel had to leave Conakry in a hurry, driven out by racketeers, moving to Guinea-Bissau and working for Brazilian missionaries for a year. He led the youth wing of President Kumba Iala’s Social Renovation Party until the military coup in September 2003. He was arrested and held in an army prison for a month. One day the prisoners were taken out to the bush and Gabriel realized that, by some extraordinary coincidence, he was close to his native village. Knowing the area very well, he was able to give his guards the slip. He swam across an estuary and walked 40 kilometers back to Bissau.

MARCUS

Marcus has no clear memory of his arrival. There was a big port, rain, and thousands of containers. It must have been somewhere big, perhaps Rotterdam or Hamburg, because he slipped through unnoticed. A man, who barely spoke, took charge of him, traveling by train to Vienna, via Munich. There someone else took over, accompanying him to the camp at Treiskirchen, where the police told him he was in Austria. “It was bitterly cold,” he said, “and the camp is certainly not the happiest place in the world, but when I got there after an exhausting journey, it felt warm. I could eat and sleep, but above all I was allowed to stay with no threats of any sort.”

This collection of maps were produced for the exhibition “WAYPOINTS LIKE SHARON S STONE”, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, 2007, and first appeared in print in Chimurenga, Vol. 14, “Everyone Has Their Indian.”

More Editorial