Archives of Womanhood and Blackness in South Africa

This exhibition at Norval Foundation shows a detailed history of pioneering Black South African female artists from 1940 to 2000.

The exhibition starts with a room titled Itinerant Archives. At its center is a vitrine with artists’ sketches and archival paraphernalia, and at one end is the eponymous text by Bessie Head, When Rain Clouds Gather. The room is run through by a timeline of the show’s framework, giving a detailed history around Black South African women artists from 1940 to 2000, interspersed with artworks and news clippings.

It is of course a truncation, but the first entry is a bolt of unexpected simultaneities: “1940 – artist Francina Ndimande is born; Artist Esther Mahlangu turns 5; Artist Noria Mabasa turns 2; Artist Gladys Mgudlandlu turns 23; Artist Valerie Desmore turns 15; Artist Dorothy Nomazotho Zihlangu Turns 20; Winnie Madikizela-Mandela turns 4.” The final entry tells us that in 1999 Thabo Mbeki was elected into power and that artist Bonnie Ntshalintshali passed. The end is marked by Bafana Bafana (1998), a woven basket by Dudu Cele.

Installation View “When Rain Clouds Gather, Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000” at Norval Foundation, Cape Town. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

As a beginning, this room reflects how the exhibition navigates its aims of being a “facilitator of cross-generational communion,” while disavowing the impossible task of giving “absolute answers about the visibility of women.” An index of six decades of pivotal moments, commemorated landmarks, and forgotten milestones, it is a confrontation with the complexity of inclusion and exclusion – comprehensiveness, unlike completion, is possible. When Rain Clouds Gather combines statements and omissions, and both its inscriptions and its gaps contain the pregnant power of vocality. Across the exhibition, the perspectives complicate in ways that form stark reminders about how even in a timeframe when Black South African womanhood was considered knowable – idiomatic rocks that can always resist striking – that subjectivity is (and always was) spectacular in its capacity for variation.

Installation View “When Rain Clouds Gather, Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000” at Norval Foundation, Cape Town. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

Following a terse section on politics, axes on the spectrum of closeness are plotted in the chapter Love/Pleasure/Intimacy. The relationships span families, lovers, and dance troupes. Under the titles A woman relaxing on her bed after a long day’s work at the Alexandra women’s hostel and A woman relaxing at the Alexandra women’s hostel (1991; 1991), Ruth Seopedi Motau presents two introspective pictures. Her attunement to her sitter crafts a visual field that imparts the sensation of eavesdropping. Her gaze gives room to the subject’s prayers, posters, and commodity aspirations, in turn asking the viewer to speculate – with an inkling – on the content of her daydreams rather than fixate on the contour of her thigh. On the other side, Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi draws attention to the uneasy line between connection and suffocation with Modern Marriage (1988); even as her hybrid throng grapples with its transdimensional union, invasion is implied in center of the image, wherein a ghostly hand holds open an eye the color of a wound. Black African Feminisms equally roves between tenderness and defiance. The dialectics between gender and power find articulation in Valerie Desmore’s paintings Red Madonna and The Hunger (1985: 1985), in which suited men suckle at the breasts of maternal deities. Through Bonnie Ntshalintshali’s sculpture Two women holding up a vessel (1990), feminism is offered as a simpler statement: unabstracted, it is located in the gesture of cooperation.

Installation View “When Rain Clouds Gather, Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000” at Norval Foundation, Cape Town. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

Gladys Mgundlandlu is the loudest voice in the Landscapes conversation. Earlier, in the matrix of archival texts, she is called “a crude Chagall” and complimented on not having “complete naivete.” But in this tableau we see the extent of the racist paternalism she was greeted with by the very extent through which her paintings broadcast that hers is a level of perception that doesn’t sacrifice warmth for incisiveness. In Houses in the Hills (1960s), the house-fronts of the township-style dwellings appear as individual faces captured in a moment of drowning; the Cape Town CBD is rendered in haughty, windy sweeps in Suburb (with Table Mountain) (1964), while Nyanga Landscape (1962) gives us a collapsed cradle – verdant and ashen but joyfully populated by figures that writhe together.

Installation View “When Rain Clouds Gather, Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000” at Norval Foundation, Cape Town. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

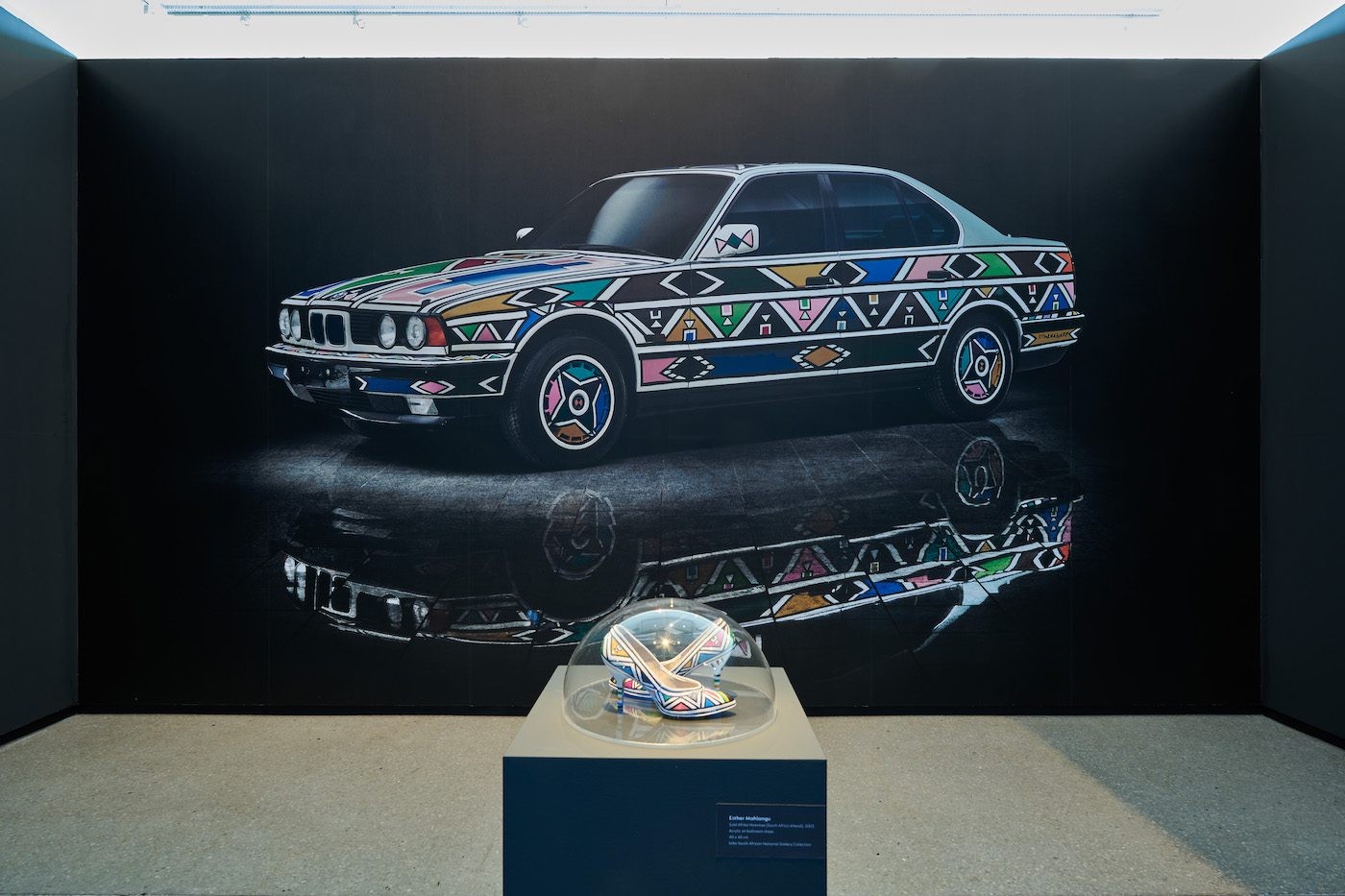

Spiritual and Religious Conjourings follows Sketches In Photo And Print and a section paying tribute to Esther Mahlangu. This section’s goal of undoing “the theatricalization of black people’s spirituality” is channelled through biblical parables in bronze and clay by Josephine Ghesa and Bonnie Ntshalintshali; punky, afro-catholic, beaded cloths by Venus Makhubela; and Seopedi Motau’s photographs of women sangomas and their trainees at Moutse caves, known as the sacred caves of the Basotho. It is the inclusion of prints by Faiza Galdhari made between 1994 and 1999, however, that ups the ante of this display. The earliest, Praying Woman (1990s), is a window into a private ritual and the last, Depths of Devotion (1999), is inscribed with scripture: “Men are rulers appointed over women/When he voices his annoyance and scolds she should not retaliate in any way.” This array of works, in unison, highlights the particular cost that women – acrosss times and places – have had to pay institutions for their convictions.

Installation View “When Rain Clouds Gather, Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000” at Norval Foundation, Cape Town. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

And as the exhibition draws to a close with Speculative Spectacular and Wrestling Traumas, it is this sense of shared experience without the diminishing of individual sensibility that comes reverberates. Noria Mabasa’s wooden pelagos, responding to the KZN flood of 1987 take on the appearance of non-denominational creation myths, echoing through to waves of monochrome solemnity in Kedibone Sarah Tabane’s In Times Of Sorrow (1990), until the flash of Fright, a 1958 painting by Desmore that, in its lurid application, seems the ancestor of a slew of contemporary works and finally, the show ends on optimistic prospect of community with, Ukhambha (1990) an intact beer vessel by Bina Gumede.

Though approximately forty artists appear, some with larger presences than others, the scope of When Rain Clouds Gather includes another thirty-three makers whose work can only be acknowledged in concept because it could not be sourced – and this is how the show becomes an iceberg that damnd us. The variety of mediums, categories of style, subjects, and perspectives points at a cultural richness that can presently only be guessed at, suggesting our shared visual inheritance would be exponentially richer if we were not looking at skill and mastery as characteristics of men but across different registers of critical and conceptual feeling.

Installation View “When Rain Clouds Gather, Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000” at Norval Foundation, Cape Town. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

Yet it is with a tone of celebration rather than accusation that Portia Malatjie and Nontobeko Ntombela have curated this exhibition. The Blackness and womanhood of these South African woman artists are not just aspects of personal identities but of political realities. When Rain Clouds Gather gives definition to what has been lost so we can better understand just how much there is to gain when insight isn’t assumed to emanate from the ideological “center.” It says there are not only artists but theoreticians, social scientists, activists, aestheticians, dream-weavers, and healers whose names have been forgotten but who should be remembered as a matter of urgency. And this large-scale speculative exhibition carries clues for where and how we can begin.

When Rain Clouds Gather: Black South African Women Artists, 1940–2000 is curated by Portia Malatjie and Nontobeko Ntombela, and shows at Cape Town’s Norval Foundation from 9 February 2022 to 9 January 2023.

Sinazo Chiya is a writer and associate director at Stevenson, based in Cape Town. She is among the 2019 writing fellows at the Institute of Creative Arts at UCT. She is the editor of Mawande Ka Zenzile’s monograph, Uhambo luyazilawula and has contributed texts to publications by Penny Siopis and Dada Khanyisa. Chiya published 9 More Weeks, a book of artist interviews in 2018 and has previously written for Art Africa, Artthrob, Adjective and the Center for Curating the Archive.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission