Focusing mainly on painting, sculpture and photography made since 1926, a recent summer exhibition in Paris surveys the enduring creative spirit of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

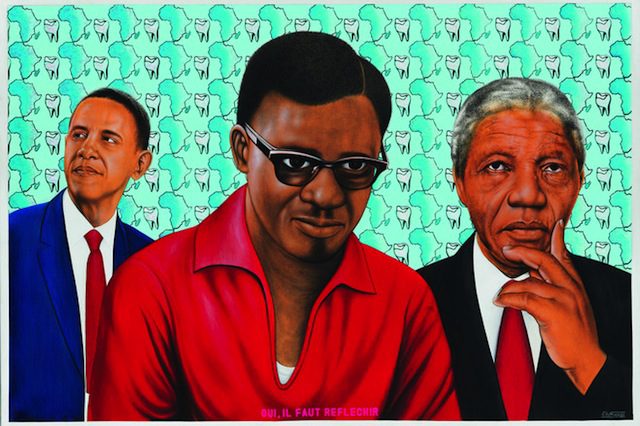

Chéri Samba, Oui, il faut réfléchir, 2014. Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 135 x 200 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: André Morin

Notwithstanding my intellectual distrust of essentialisms and my bent for postcolonial skepticism, I am struck by a certain “look” the minute I walk into Beauté Congo. It’s not quite “le look Africain” or anything so grandly patronizing, but I am aware of what the curator of the exhibition André Magnin has described in the catalogue as the art works having “the same sense of belonging to a vibrant Congo…”

Of course, we are dealing with André Magnin here. What is on show is as much his curatorial eye as the art itself. The man who brought us “Africa” in the provocative and controversial Magiciens de la Terre exhibition in 1989; who has curated Italian business man Jean Pigozzi’s highly idiosyncratic Contemporary African Art Collection; who brought photographer Seydou Keïta and painter Chéri Samba to Western markets; and who, at his gallery Magnin-A in Paris, has championed many emergent artists, has mounted an overview of modern and contemporary art here – primarily taken from European collections, some from colonial archives in Brussels, with a few works from the artists’ own collections in Kinshasa – giving the subject his discerning eye, but also some historical scope and artistic depth.

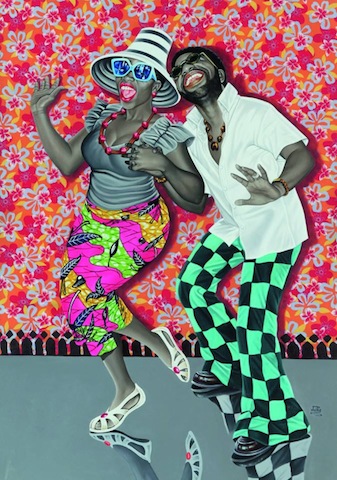

Clearly lessons have been learned. After the criticisms directed at Magiciens – that it showed a preference for self-trained artists, that it presented Africa as a magical place devoid of chronology, that it decontextualized art works – and the many debates that circulated subsequently on the state of global art, Magnin has probably taken some of these debates to heart. This is well illustrated in the choice of JP Mika’s flamboyant Kiese na Kiese (Joy for Joy) as the flagship image for the exhibition.

JP Mika, Kiese na kiese, 2014. Oil and acrylic on fabric, 168,5 x 119 cm, Pas-Chadoir Collection, Belgium. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Antoine de Roux

Mika, born in 1980, first worked as a young sign painter in Kinshasa, but then attended the Academie des Beaux-Arts in Kinshasa and worked in the studio of the popular painter Chéri Chérin. As such, Mika is the perfect bridge between these different and often conflicting accounts of African art: on the one hand, he is well-versed in the sign-painting genre that has brought autodidacts such as Chéri Samba and other members of the so-called School of Popular Painting in Congo to an international market (hungry for an exoticized and “naïve” art); on the other hand, he is also trained at an art school and exhibits the skills of that instruction. His large, colorful portraits may share the directness of popular painters like Samba and Moke, but they are also accomplished, perceptive, conceptual, and witty. He self-consciously references the history of representation in the Congo in his large paintings done on colorful cloth, nostalgically invoking the studio photography so popular in the 1960s.

It is a pity that the exhibition does not explore these diverse stylistic influences further, potentially situating Mika as a bridge, an example of possible continuity between different art forms that have all vied for attention in the public’s often fragmentary perception of Congolese art: popular photography, sign painting, and contemporary art inform each other effortlessly in Mika’s work.

As it is, the exhibition literally “splits” into distinct streams: turn left upon entering and we are in the midst of the so-called Popular painters: brightly colored canvases, often annotated with text and speech bubbles, comment on everything from politics to education to morals. These artists like Chéri Samba, Moke, Pierre Bodo, and others are mostly from in and around Kinshasa. A true overview of Congo might have included Tshibumba Kanda Matulu who worked in Lubumbashi in the south in the 1970s in a similar style.

Djilatendo, Sans titre, c. 1930. Gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 18 cm. Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren, HO.0.1.3371 © Djilatendo. Photo © MRAC Tervuren

Turn right, and we enter the 21st century where “Young and Emerging Artists” use photography, video, collage, and painting to experiment with artistic forms in works that encourage critical reflection. Often centered on collectives coming out of art school such as the Academie in Kinshasa, these artists represent an important counterweight to the over-exposed works of the sign painters, even though the works selected here are still mostly wall-based. I was left wondering about the absence of sculpture, installation or performance art – are these part of the contemporary art world in Congo? In addition, I was expecting works that are more politically engaged, reflecting not only on a violent colonial history, but also on the on-going civil conflicts in the east of the country, so strikingly portrayed by Irish artist Richard Mosse. Here, the photomontages of rising star Sammy Baloji are about as political as these works get. Baloji juxtaposes ethnographic colonial photographs of François Michel with beautiful watercolors made by Leon Dardenne in Katanga in the late 1890s. This results in strangely disturbing composite landscapes that embody the violence committed against that land. Pathy Tshindele’s paintings comment on the interference of superpowers in African politics when he dresses various world leaders in the costumes of the Kuba; Kiripi Katembo photographs a gritty Kinshasa as it is reflected in its dirty puddles; Steve Bandoma incorporates recycled materials in collaged portraits – not unlike Kenyan Wangechi Mutu’s – in his series on the Ali-Foreman boxing match held in Kinshasa in 1974.

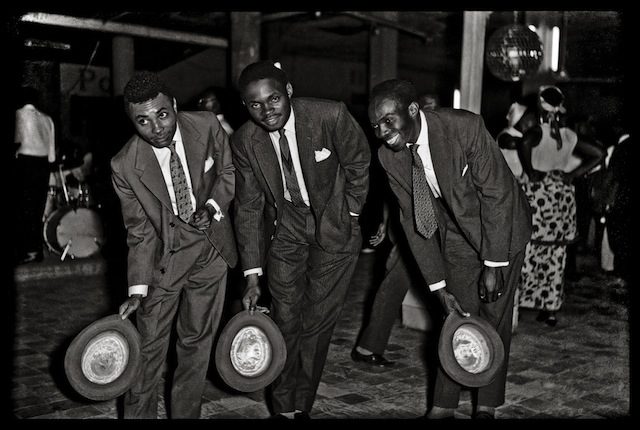

The more historical side of the exhibition is located downstairs. In the 1920s, a Belgian official named Georges Thiry provided Albert and Antoinette Lubaki with paper and watercolor in an effort to capture the drawings they were making on the outside walls of their huts. These early watercolors are beautiful records of local fauna and flora and village life. Unfortunately, once the supply of art material stopped we lose trace of these artists around the 1940s. This is followed by work from the 1940s and 50s when the Atelier du Hangar was established, a group of artists who, under the auspices of a French amateur artist were encouraged not to follow any “European” conventions but to let their creativity flow. The result is these distinctive, if somewhat repetitive, canvases of natural imagery against decorative, all-over backgrounds. Here we also find the black and white photographs of the Angolans Jean Depara and Ambroise Ngaimoko, who respectively chronicled the nightlife and fashion of Leopoldville (Kinshasa) in the 1950s and 1970s, revealing the social aspirations of an urban class.

Jean Depara, Untitled, c. 1955-65. Gelatin silver print, 77 x 113 cm. Collection Revue Noire, Paris © Jean Depara. Photo Courtesy Revue Noire

In case these historical documents are a little on the dry side after the exuberance encountered upstairs, Magnin has installed here some of the fanciful large-scale model cities designed and built by Bodys Isek Kingelez, another artist that rose to fame after Magnin included him in the Magiciens show. His fantastic futuristic cities are constructed out of recycled cardboard, plastic, bottle tops, and tinfoil. Like the imaginary machines created by Rigobert Nimi, also on show here, they are utopian dreams for African cities.

These unusual and unconventional art works exemplify Magnin’s curatorial approach: always fascinated by the humor and innovation that he pursues in African art, he wants to share with the viewer the energy that has always enchanted him about Kinshasa, a city he has come to know intimately through repeated visits and extended networks.

The exhibition succeeds in communicating this energy, and it also gives some insight into the broader history of the art of Zaire-Congo. It may be too focused on just one city, it may be silent on many aspects of the violent history and ongoing conflicts in the DRC, but it is nevertheless an exhibition very much worth seeing, offering much to learn, and even more to enjoy.

We can only hope that Beauté Congo will also travel to the DRC for the Congolese to properly claim and own their artistic heritage, rather than simply gathering this work for the enjoyment of European audiences.

Liese Van Der Watt is a South African art writer based in London.

More Editorial