Despite featuring a few strong works, the Jamaica Biennial 2017 lacks in curatorial vision with contrasting aims and ambitions. Our author Seph Rodney went to Kingston to review the exhibition.

KINGSTON — It was too loud. Though the tune was pleasant — a Miles Davis’s track — I couldn’t hear what the students were saying about their work. I was a panel member attending a session at the National Gallery of Jamaica, on hand to volunteer critiques of the portfolios of the visual arts students from the Edna Manley College of the Arts. However, the recital from the musicians next door interfered with the speeches. Similarly, the entire Jamaica Biennial of 2017 was conceived in contrasting aims, interests and ambitions and thus was not ever really able to cohere. As the National Gallery’s senior curator O’Neil Lawrence admitted, “We know that it is an ugly baby… and we birthed it.”

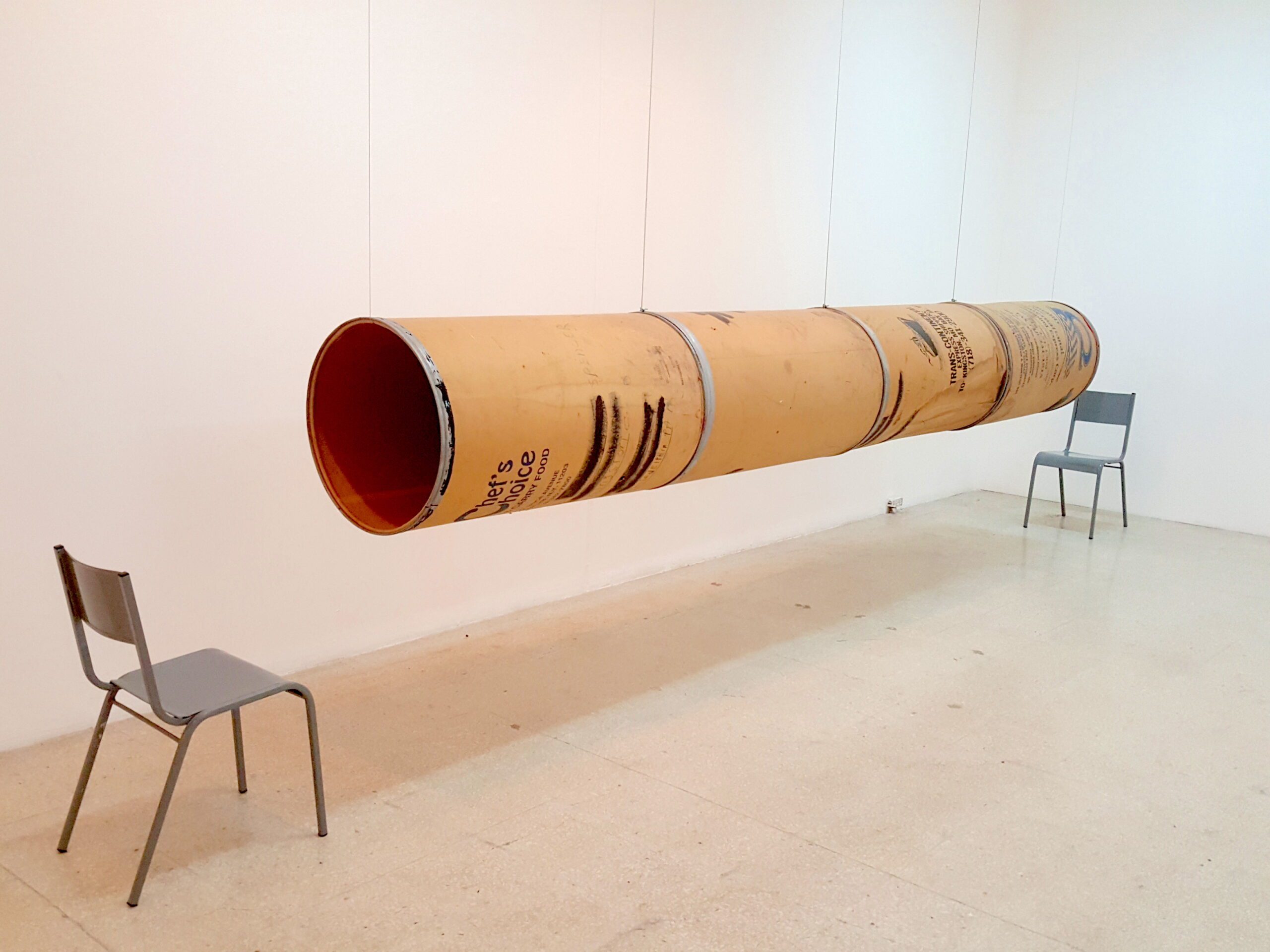

Installation view of the Jamaica Biennial 2017 at the National Gallery in Kingston. Courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

What caused the exhibition to be look like a gallimaufry was not the curatorial team, but rather the very structure of the show. The Jamaica Biennial 2017 actually consisted of four exhibitions at multiple sites, stitched together under the “biennial” rubric. National Gallery director Veerle Poupeye explained the structure: there is a juried section chosen by a panel of artists, dealers, gallery directors, and curators; works by about half of a group of 72 “invited” artists who have been given a permanent offer to participate in the show by the National Gallery’s Board of Management; small tribute sections to the traditional, figurative painter Alexander Cooper and the recently deceased photographer and self-proclaimed “media terrorist” Peter Dean Rickards; and a selection of pieces by artists from the Caribbean and the Caribbean Diaspora, grouped under the rubric of “special projects.” Poupeye told me that the final tally was about 160 artworks installed at the National Gallery, the exhibition’s original home; a historic building known as Devon House; and the National Gallery West in Montego Bay. As Petrona Morrison, an artist with work in the show and a former member of the gallery’s board, said in the closing weekend’s final public panel, the biennial “is trying to be all things to all people.”

Leasho Johnson, “In the Middle” (2017), Dutch pots, speakers, clay, variable dimensions. Photo by Randy Richards. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica

Poupeye mentioned she would prefer to mount a thematically arranged, juried exhibition that does what many biennials do: introduce to the international art community the work of artists from a particular geographical area. However, in its current configuration, the Jamaica Biennial is also the means by which some local, legacy artists are able to show their work at the National Gallery. Their pride is sustained, but at a cost. Mostly the show read like a series of discordant arguments, rather than works in conversation with each other.

Cosmo Whyte, “Golden Kicks/Where You Get Dem Clarks (2016), charcoal and gold leaf on paper, 84 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica

One of the rare exceptions to this overall layout was the room that contained Cosmo Whyte’s Golden Kicks/Where you Get Dem Clarks (2016), a washy charcoal drawing of a troupe of dancers wearing what look like grass skirts. Whyte’s figures are interspersed among bundles of tied vegetation and a copse of trees in the same hue and tone, but the dancers are recognizable by the gold leaf shoes on their feet. Whyte’s drawing created a quiet mood which lent a sense of serene contemplation to Nadia Huggins’s Is that a Buoy? (2015) on the opposite wall. In Huggins’s work, a photograph diptych and video, the figure becomes lost in the watery scene, so that its head floating just above the water line is only barely distinguishable from a buoy. Though other parts of the show never became as lucid to me as this room, there were several standout pieces.

Nadia Huggins “Is that a Buoy” (2015) digital photographs and video diptych, each 76.2 x 50.8 cm, duration: 3:00 minutes. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica

Claudia Porges Beyer’s Splendour in the Grass (2015), which consists of a pair of Manolo Blahnik mules submerged in water on top of a bed of green sea anemones inside a medium-sized briefcase. It’s a wonderfully clever surrealist object that signals the fetishizing of a symbol of hyper-femininity and high social status. Simon Benjamin’s Urban Beaches: FORUM IV (2016) also employs water, but along with small white stones and precise lighting he uses it to create small oases. Phillip Thomas’s installation High-Sis in the Garden of Heathen (2017) has a figurative painting at its center — a mesmerizing portrait of a man with camouflaged hair and a shower of star shapes and medals glittering around his face and on his clothing, as well as an ominous rifle visible in the background. It is an image that stretches the romanticization of military force until it breaks. Marlon James’s portrait photographs of random people are compelling for the characters they display. For instance, Blackout: Kingston 12, Jamaica (2013-14) features someone of ambiguous gender with purple lips and deeply yellow eyes, gazing inscrutably into the camera.

Simon Benjamin, “Urban Beaches: FORUM IV” (2016), white marl stone, gold paint on plastered plyboard, video projection. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica

Several people I spoke with, including members of the management board, artists, and curators, related that the National Gallery’s previous director, David Boxer, wanted to keep the invited list, while younger members want to jettison that aspect and move the biennial towards a more cohesive, thematic model. Clearly, if the next biennial is to succeed, firm decisions will have to be made and a consensus reached about what the organizers want the Jamaica Biennial to do and be.

Seph Rodney, PhD, was born in Jamaica and grew up in New York City. He is a staff writer and editor for the Hyperallergic blog, writing about contemporary art and related issues. He has written for CNN Op-ed pages, and for Artillery Magazine. He has taught at Parsons School of Design and is slated to be an adjunct professor at the School of Visual Arts in the fall.

More Editorial