Caught up in Poland’s COVID-19 lockdown, Bob-Nosa Uwagboe opened his solo exhibition on May 23 at the National Museum in Gdansk. C& author Agwu Enekwachi writes about Uwagboe’s tenacious artistic journey while confronting his dark representations of the social ills which threaten our existence as much as the current virus.

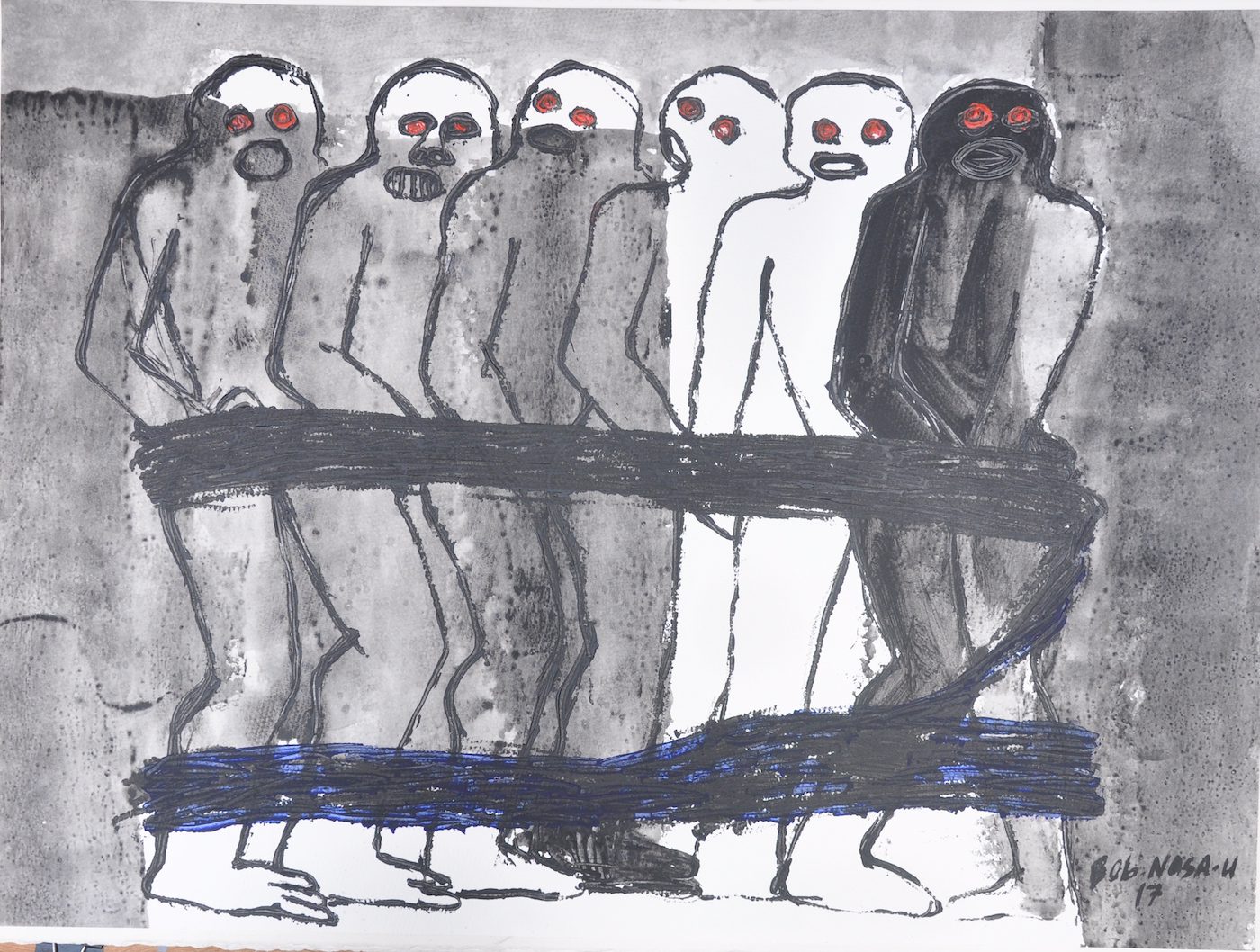

Bob-Nosa Uwagboe, A drawing from the Human Merchandise Series, 2019. Acrylic on water color paper.

A boldly written inscription welcomes visitors to the exhibition hall. “The Protest Art Studio” it says, announcing Bob-Nosa Uwagboe’s solo exhibition Transit at the National Museum in Gdansk. The show comprises thirty mixed-media paintings and fifty-nine drawings on watercolor paper spanning the themes that have engaged the artist for over two decades. Uwagboe’s work is inspired by the socio-political conditions in his homeland, Nigeria. He looks at corrupt leadership, domestic violence, police brutality, migration, and the direness of the human condition. Even in a time when art seems to serve a consumer culture and protest art has left canvasses for the convenience of social media, his message has remained attentive to his original creative goals.

“The Protest Art Studio”, Installation view of Bob-Nosa Uwagboe’s solo exhibition Transit at the National Museum in Gdansk, 2020.

Uwagboe inadvertently started making protest art in the late 1990s as a student at Auchi Polytechnic in Edo state. “My love for the social commentaries embedded in reggae music in the 1980s and 1990s, the unfairness that surrounded MKO Abiola’s loss in the 1993 presidential election, the unrest, insurgencies and displacements in parts of Nigeria,” he says, were among some of the experiences that shaped his artistic path. For Uwagboe, it is complex leadership deficiencies that compel people to emigrate to undreamed of places, and he is not interested in such movement despite the palpable disillusionment that may be around him: “Our country is our home, and we must make it better. My art is an instrument that will help bring that change,” says Uwagboe.

Uwagboe’s paintings are often peopled with ghoulish images that seem to linger on the threshold between life and death. These brutal anthropomorphic images are the expressions of his angst, while his palette of dark, shadowy, and raw colors reinforces his messages. A prominent device in Uwagboe’s work is nakedness. He uses nudity to symbolically portray the beastly nature of some humans in power, as well as the extreme deprivation and dispossession that the masses are forced to endure. Among some Nigerian cultures nakedness is an extreme protest tool, resorted to when other attempts fail. Yet the metaphor of nakedness is conceptually stretched so that decaying flesh reveals parts of the skeletons of Uwagboe’s forms. The artist also references death and the decay of corruption by using titles such as The Mourners, Rest in Peace, Legless Leader, Dying in Power, and Obituary (this latter being the title of his second solo exhibition, held in 2018). The resulting paintings are very powerful.

Bob-Nosa Uwagboe, The Mourners, 2019, 153cm x 153cm. Acrylic, Spray paint on textured Canvas. Photo: Dolapo Ogunnusi

In recent times Uwagboe’s work has been well received, but it was not always the case. His first solo exhibition, in 2011, faced rejection. “Some people think that my work is offensive,” he says. “I could not get collectors or patrons interested. People said that I would not get anywhere with my kind of art. But I didn’t give up, because I believed I had found my voice and would not lose it to mundane considerations.” While dealing with the rejection of his art at home, he secured exhibitions, residencies, and patronage in countries such as Cameroon, Argentina, Spain, and the US by reaching out to the world through social media.

Although Uwagboe is majorly inspired by the social challenges in his country, people elsewhere can also relate to his messages about police brutality, domestic violence, forced migration crises, human rights abuses, and the overbearing nature of state power in the hands of bad leaders. Such is the transcendental nature of Uwagboe’s art, which resonates among different peoples of the world. “Most of what I do I call global validity,” he says. “My work portrays messages that are both local and universal. The human experiences I express are obtainable in one form or the other in any place, because life is similar everywhere.” In his 2019 exhibition in Barcelona, the theme No to Domestic Violence reverberated as it did in Nigeria. In his current body of work in Gdansk, works like Poisoned Teaand Black on Black Violence portray messages about the treachery of leadership and the reciprocity of violence, which people there can no doubt relate to.

Using the work Poisoned Tea as a reference, South African artist and art educator Annette Loubser makes a comparison between corruption and the current virus in her catalogue essay for the Transit exhibition. She writes how these negative elements “contaminate our time, lives, families and futures.” She notes that the tea metaphor is very powerful because it causes one to wonder about COVID-19’s relative innocence compared to all the conspiracy theories that surround its emergence. Loubser argues that we have to learn not to corrupt the natural order of things because we will lose our humanity in the process. Even if we might become vulnerable thereby.

The currency of Uwagboe’s work doesn’t suggest immediate connections with the pandemic; it is existential realities of fear, death, vulnerabilities, protest, and powerlessness produced by both corruption and the virus that connect them. It is in this regard that Uwagboe’s art continues to be constantly relevant and in transit.

Agwu Enekwachi is a PhD student in Art History at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He is an artist, teacher, and culture writer living in Abuja.

More Editorial