The Young Lords, a radical social activist group founded by Puerto Rican youth in 1960s USA, are the subject of a timely multi-venue exhibition in New York.

Maximo Colon, Untitled, c. 1970, Digital print. Courtesy of Maximo Colon

The Young Lords were a group opposed to racism who demanded equality in healthcare, better education and increased access to services for the poor working-class, fought police injustice, and advocated for attainable food and child care options. In New York, its primary purpose was to fight for the daily injustices faced by the Puerto Rican community that at the time (and to a lesser degree today) faced a myriad of socio-economic adversities and was largely ignored by local city government. In their political ideology the Young Lords modeled themselves on the Black Panthers, the black Nationalist group founded in the mid-1960s that used militancy as a means of demanding justice. The Lords’ style choices reflected the Panther’s dress codes, including the use of combat boots, berets, and army-style fatigues.

The Bronx Museum of the Arts, in collaboration with El Museo del Barrio and the Loisaida Center, has curated a three-part exhibition that documents and honors the legacy of The Young Lords. ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York spans across three neighborhoods where the Young Lords were most active in the New York City area.

Caecilia Tripp, Video Still from “Music for (prepared) Bicycles,” Score Two New York, Brooklyn/Spanish Harlem/The Bronx, 2013, HD video, 14 minutes. Courtesy of the artist

On the Lower East Side, where the group was founded, The Loisaida Center pays particular attention to the art created by the group. The Lords recognized that art was an important part of the process of community-making; they knew that taking ownership of and having pride in one’s history and culture was a way of occupying spaces in which they were regarded as “foreign” and “other.” Much of this exhibit is focused not just on social activism, but on the effects of that activism on artists, reflected in photographs and videos on display including the work of photographers like Hiram Maristany and Maximo Colon. The curators also draw attention to the group’s communal art history by recreating makeshift tents, which served as homes and villages for some artists. The group once turned a building in this area into an artist space known as the New Rican Village, where they used theatre and art as part of their political arsenal. The exhibit at The Loisaida Center also pays close attention to the role of gays and lesbians in the movement, as this neighborhood was the site of the Young Lords Gay and Lesbian Caucus. A video plays on the wall with footage of transgender activist Sylvia Rivera demanding respect and visibility from her peers.

The exhibit in the Bronx Museum of Arts highlights, among other things, the group’s takeover of Lincoln Hospital in this neighborhood after children suffered poisoning from lead exposure after being admitted to the hospital. One installation looks at members of the Young Lords Women’s Caucus, a group that demanded equal treatment for its members and focused on women’s issues. Similarly, a few pieces of art in the Bronx Museum also focus on the Young Lords’ call for an end to the forced sterilization of Puerto Rican women on the island and elsewhere. In the middle of the gallery is a pair of Nike Air Force One sneakers, designed by Young Lords member Miguel Luciano, where the infamous Nike “swoosh” is changed into a machete. Young urban communities, like the one in the Bronx, place great emphasis and value on sneakers, so this inclusion has cultural resonance and comments effectively both on deadening consumer practices and, paradoxically, on the possibility of revolution.

Miguel Luciano, Machetero Air Force One’s (Filiberto Ojedo Uptowns), 2007, Vinyl and acrylic on sneakers. Courtesy of the artist

The final location of the exhibit at El Museo del Barrio is at the site where the Young Lord’s garbage-dumping protests and their peaceful occupation of the First People’s Church occurred. Puerto Rican Obituary, a poem by Lords member and poet Pedro Pietri, plays on a loop in the museum opposite a wall adorned with four semi-automatic weapons. Each weapon is emblazoned with a word: “Health,” “Food,” “Housing,” and “Education.” Both pieces – the poem and the weapons painted with slogans – illustrate that what was at stake was literally the life and death of the Puerto Rican people: without the mobilization and awareness that the Young Lords brought, local officials would have continued to view this community as invisible, and pretended they didn’t need basic services that were available to more affluent, white inhabitants.

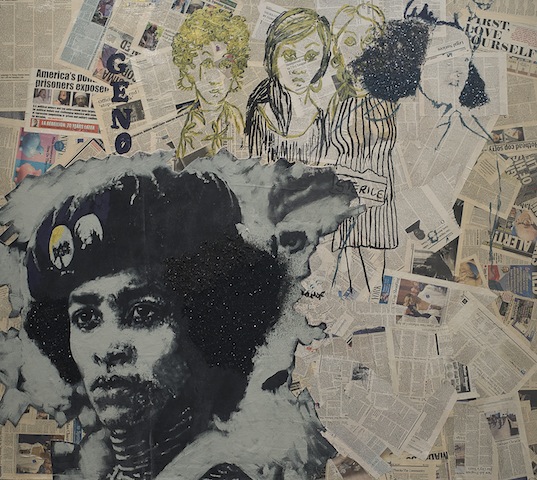

Sophia Dawson, Sistahz, 2015, Acrylic and collage on canvas, 64 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist

The three exhibits are striking for many reasons but one in particular stands out: the photographs and art are filled with black and brown faces, reflecting that Puerto Ricans are comprised of mixed and multi-ethnic lineage. Often, in Latino communities, the darker you are, the less status you have, the less beautiful you are, the less you matter. Those who are “dark” are excised from the albums of family history, and even national history. But these faces – which could once again have been erased from memory – are on full display here, on the frontlines of this movement. It is no coincidence, then, that the Young Lords aligned with the Black Panthers. In New York City, Blacks and Latinos live in shared neighborhoods, face the same injustices and endure the same hardships. For all intents and purposes, the two groups are the same. It’s impossible to overstate just how relevant a group like the Young Lords feels in today’s political and social landscape.

The group’s rallying call – which was also the name of their organizational newsletter (on display in all exhibits) – was “P’alante” which is a shortened version of the Spanish phrase “para adelante”, meaning “moving forward.” In 2015, Americans are still looking to do the same. An exhibit like ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York allows us a moment to look back at how far we have come. Or how far we haven’t.

Madonna Hernandez is a writer from Brooklyn, New York, born and raised there before gentrification. She is interested in examining issues of identity, race, class and social structure, through her writing.

More Editorial