The Indonesian city of Yogyakarta is one of the most important centers of contemporary art in Southeast Asia and home of the Biennale Jogja, an art showcase with a progressive agenda.

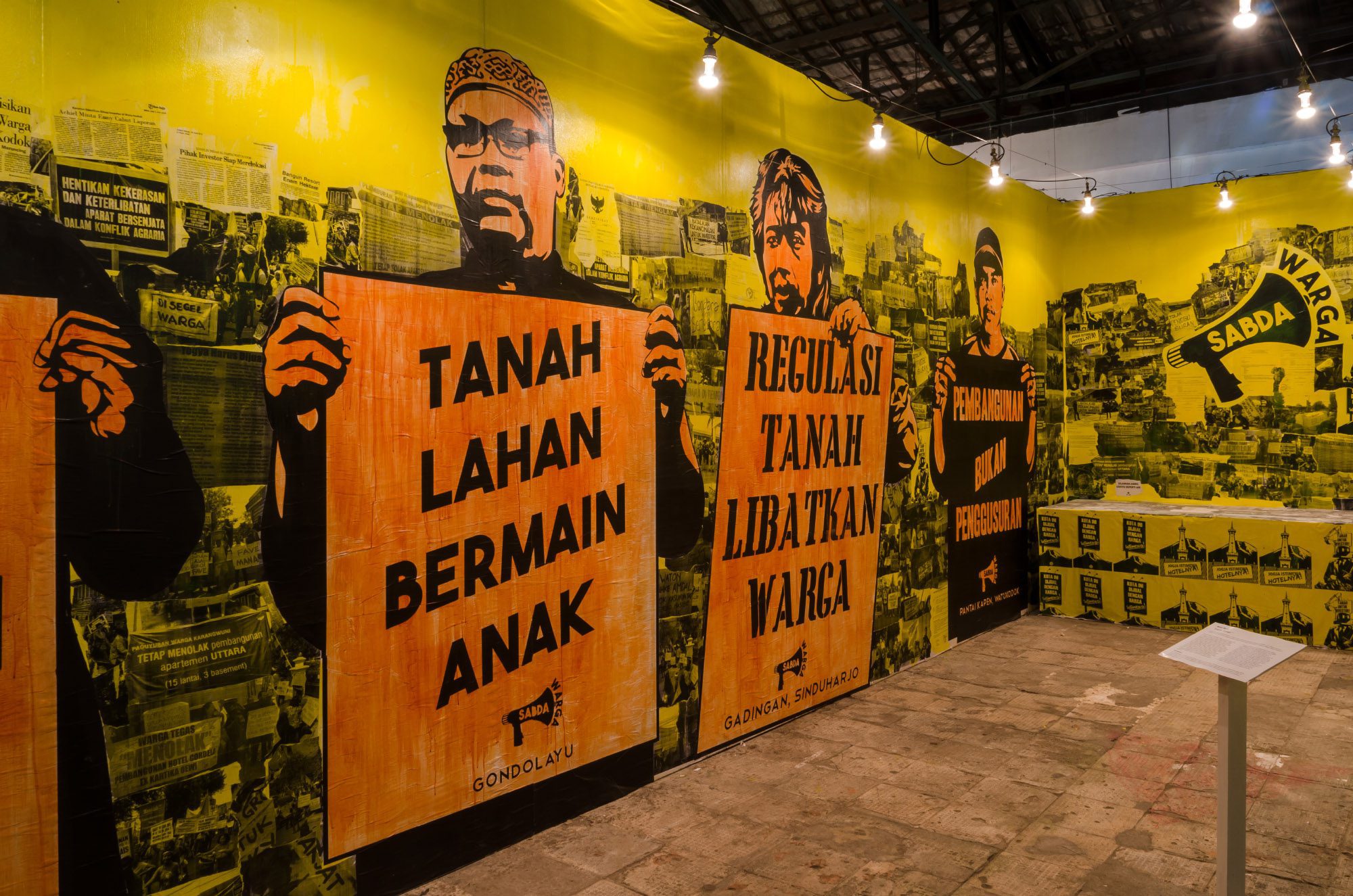

Anti Tank, Sabda Warga, posters and archival documentation. Photo credits Kelas Pagy Yogyakarta and Biennale Jogja XIII

Few places in Indonesia display the country’s cultural diversity as vividly as Yogyakarta, in central Java. The largest university town within the 17,500-island archipelago brings together Indonesia’s more than 300 ethnicities, who boast a wide variety of religions and languages. It is also a place where ancient traditions encounter modern lifestyles. Thanks in part to its medieval Buddhist and Hindu temples, the autonomous Islamic sultanate is the nation’s second most popular tourist destination after Bali – as well as one of the most important centers of contemporary art in Southeast Asia.

No wonder Biennale Jogja, the city’s biggest art event, is one of the most influential national art fairs, alongside the Jakarta Biennale. The organizers have selected Nigeria, an equally multifaceted country with many social and historical parallels to Indonesia, to be this year’s partner country. Under the banner of “Hacking Conflicts,” the artists will get to the roots of their common history and present and the many social and political conflicts in both places – but also learn about the everyday life and culture of the other country.

Segun Adefila, Kongi’s Harvest by Wole Soyinka, play, July 28, 2015 at University of Lagos. Courtesy of Biennale Jogja

Ever since the war of independence in the late 1940s, Yogyakarta’s artists have been well-known for their social and political engagement. In 1950, a system of shared studios known as sanggars grew into the first Indonesian Academy for Fine Arts (now known as the Indonesian Institute of the Arts, or ISI). However, after the autocratic General Suharto seized power in 1965, socially critical art and political messages became taboo. So when the urban cultural center Taman Budaya organized the first “Yogyakarta Painting Exhibition” in 1983, it was limited to aesthetic considerations. Five years later the event was renamed the Biennale Painting Yogyakarta, intending to serve “as a barometer of activity and the level of creativity of the artists, as well as the public’s appreciation,” in the words of Rob M. Mujiono, who was head of the cultural center at the time. Yet the show only admitted two-dimensional artworks by “professional” painters above age 35.

In protest against the restrictive selection criteria, a number of young artists initiated a parallel event in 1992: the Binal Experimental Arts. The name plays on the Indonesian pronunciation of the foreign word “biennale,” which is pronounced like “binal,” the Bahasa Indonesia word for “naughty.” The artists of the Binal exploited all artistic means at their disposal. They put on site-specific installations and performances around the city, held exhibitions at private studios, and hosted public discussions. With more than 300 participants, the entertaining offshoot event stole the spotlight from the official one in both attendance and media coverage. The lesson sunk in. Two years later, the city invited artists from all disciplines to a “Variety of Arts” exhibition, which in 1997 was renamed the Yogyakarta Art Biennale. Instead a jury, a team of curators now made the selections.

Because of the political changes after Indonesia’s democratization in 1998, there was no public funding for the art event in 2001 and the biennale was not held. Consequently, for the first time in 2003, a commercial gallery sponsored the exhibition, which has had a general curator ever since. With the new name Biennale Jogja, it quickly regained stature, especially as the only comparable event in Indonesia, the Jakarta Biennale, was on hiatus from the collapse of the Suharto regime until 2006. By 2009, Biennale Jogja’s funding was again in jeopardy, with scant official support. So the city’s artists mobilized themselves. Taking inspiration from the Javanese system of gotong royong, or voluntary mutual aid in the community, a local movement sprouted with more than 300 participants who exhibited their work in numerous public spaces as well as the city’s art gallery.

That the major art event had again come so close to disintegrating demonstrated the biennale’s urgent need for ongoing, professional management. “In Indonesia there are neither state museums nor an infrastructure for contemporary art. And thus independent cultural organizations are still the only alternative to commercial galleries. The latter… have so far mostly received support from foreign countries. Now it’s time that Indonesian sponsors begin to grasp how much they can profit from a vibrant art scene,” explains the Dutch artist Mella Jaarsma. Some 27 years ago, she and her husband Nindityo Adipurnomo had opened the Cemeti Art House in Yogyakarta, the first contemporary art gallery in Indonesia. In 2010, together with other influential artists in the city, they founded the state-funded Yayasan Biennale Yogyakarta (the Yogyakarta Biennale Foundation), which has been charged since then with managing the biennial exhibition.

Victor Ehikhamenor, ‘The Wealth of Nations’, Installation, Drawing, Drum, Water. Photo Credits Kelas Pagi Yogyakarta and Jogja Biennale Jogja XIII Kopie

With the restructuring came a new concept. Through 2022, Biennale Jogja will be focusing exclusively on countries in the equatorial region. The objective is to break out of the entrenched geopolitical parameters of north and south, center and periphery, and rich and poor that have come to dominate the global discourse around contemporary art. The idea was inspired by Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, who co-founded the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1950s. He also spearheaded the first African-Asian conference, held in Bandung in 1955, whose participants self-identified for the first time as the “Third World” – distinguishing themselves from both the former colonial powers’ conservative West and the Soviet Union’s socialism. The former colonies wanted to re-emphasize their own cultural identity.

The partner country of the first biennale in the equatorial series, in 2011, was India. Titled “Religiosity, Spirituality, and Belief” the show featured many works portraying religious practices and faith as important elements of contemporary society in both India and Indonesia. Some artists, however, directly addressed the conflicts that arise in the name of religion: “The common ideals of diversity and peaceful coexistence are now under serious threat from fundamental forces – in India from the radical Hindutva, and in Indonesia from Islamists,” explained the Indian co-curator Suman Gopinath.

“Movement” was the promising theme of the second equatorial biennale in 2013, which focused on the partner countries of Egypt, Yemen, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. But anyone who read the title “Not a Dead End” as an artistic reference to the Arab Spring left disappointed. In fact the term movement was referring to actual motion or mobility – which many critics saw as a cowardly move. By contrast, this year’s theme of “Hacking Conflict” braves a volatile topic in the third biennale of the equator series, partnered with Nigeria. “Hacking means harming or destroying an already established system. But that doesn’t automatically need to be negative,” explains Alia Swastika, who has been the biennale’s director since 2014 (see interview). “Disrupting and stirring up an entrenched system can create a new situation that leads to a stronger society. Both Indonesia and Nigeria have plenty of experience with such conflicts.”

Note: The various spellings of the city Yogyakarta are due to spelling reforms over the course of the past century. Both spellings are acceptable, but “Yogyakarta” is used more for official and formal situations. “Jogjakarta” – or “Jogja” for short – is more contemporary.

Christina Schott has been working as a Southeast Asia correspondent for weltreporter.net for more than ten years. She specializes on art, culture, society, and the environment.

More Editorial