Cédric Vincent writes about the importance of remembering pan-African events

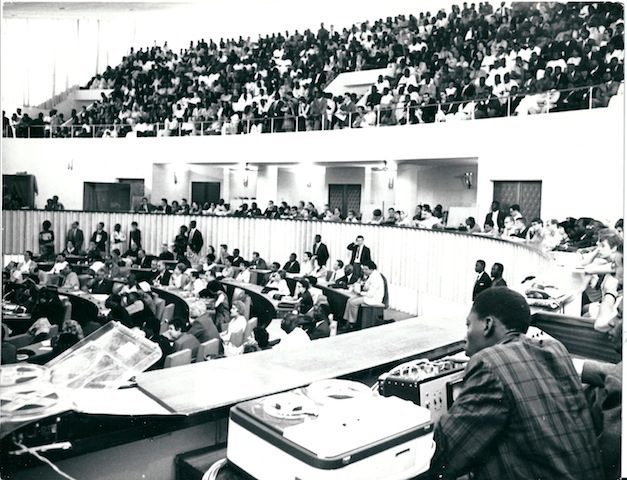

Symposium during the World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar, 1966 (courtesy of Panafest Archive research project)

Independence gave rise in Africa to a proliferation of festivals of art and culture, symposia, and gatherings on musical and later cinematic themes. This emerging scene felt the lasting imprint of a number of massive pan-African events held in various countries. Four in particular were radically new phenomena for their time and deserve special attention:

Those four festivals followed fairly similar models. They featured delegations from around the world and were attended by tens of thousands of visitors. The festivities created encounters between music and fine art, theater and cinema, dance and literature, and in one case even included one of the most ambitious sporting events ever organized on the continent. There were panels and round-table discussions by the score. Grand avenues were added to the map and imposing structures built (such as the Dynamique Museum in Dakar and the National Theater in Lagos). Even entire neighborhoods were erected (e.g. Festac Town in Lagos), profoundly transforming the fabric of the host cities. The budgets were dizzying and the infrastructure was a complex financial undertaking.

The festivals of Dakar, Algiers, Kinshasa, and Lagos left their marks on the pan-African cultural landscape, on the continent both north and south of the Sahara, and even further afield, inspiring people in the US, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the islands of the Indian Ocean. Strangely enough, however, they have not received much attention from academics and have never been the subject of a collective study to date. This is a crucial oversight that essentially consigned an entire chapter of cultural and political history in the postcolonial period to the dustbin. The team of the Panafest Archive research project (EHESS-CNRS, Paris) is now working to fill that gap.

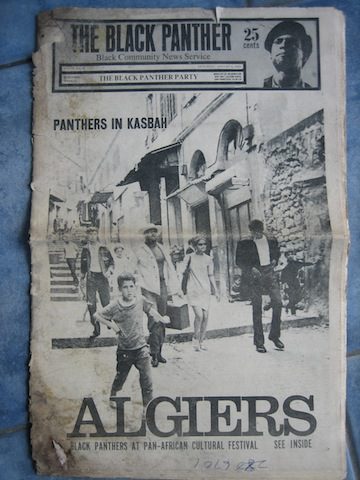

As shown above, the grand events in question had a global impact and continue to be remembered as symbols of a cultural Golden Age. They owe this memory to their political character. It would be inaccurate to think of these four festivals as “mere” cultural and artistic events. Rather, they were central nodes in a network of relations and representations, situated at the very heart of movements that had fundamental global effects on the structuring of the nation-state and the incipient political imaginary. As sites of coordination and mediation between artistic creators and decision-makers on one side and widely disparate audiences on the other, they served as sounding boards for the public dissemination of ideas that had previously been confined to the elite. As showcases for the states that organized and participated in them, they served as entranceways – via the artists’ work – for diplomacy around various issues at various scales: among young African nations, between culturally Arab North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, between independent countries and liberation movements in the remaining colonies and apartheid regimes, between the Americas and Africa, between former metropolises and former colonies, and between international organizations and bilateral cooperation structures.

Apart from ideological rivalries (notably over the notion of Négritude) among the events, which greatly contributed to shaping their contours, it is fitting to think of the festivals in Dakar, Algiers, Kinshasa, and Lagos as collectively opening a space for interchange and encounter. The delegations’ artists and cultural players engaged with one another, made each other’s acquaintance, exchanged ideas. It is important to situate them in connection with one another and with a view to the transfer (that is, recycling) of ideas, practices, and images as well as the flow of people, objects, and symbols.

The Black Panther newspaper, 1969 (courtesy of Panafest Archive research project)

This stream of memory took form in different kinds of artistic events via the rediscovery and reuse of intellectual and artistic productions linked to the agitated years of anti-colonial struggle and the attainment of independence. Moreover, these events’ affinity for commemoration has been expressed through explicit references to historical festivals, notably through the anniversaries of independence. The Second Pan-African Festival, for example, was held in Algiers in July 2009. Then, in 2010, the third World Festival of Black Arts was organized in Dakar, not without difficulty. The theme was African Renaissance, a buzzword coined by the former president of South Africa Thabo Mbeki in a bid to redefine the international image of the continent. Prior, the various organizers of the Dakar Biennale had made recurrent references to the 1966 festival in order to raise the profile of their own event. Finally, in South Africa, an abortive project intending to resurrect the FESTAC was developed in the late 1990s after the abandonment of the Johannesburg Biennale. These projects all demonstrate the extent to which the memory of those festivals permeates the world of art and culture in Africa.

At the same time, the references to festivals in the 1960s and ’70s are often stereotyped and billed as canonical, pioneering points of departure. The images and discourses they have produced are recycled, but always draw on the same sources (catalogues, memorial books, etc.). In cases where the stereotypes could be contested, the dearth of documentation frequently leads to a kind of amnesia-fueled nostalgia. It bears pointing out that festivals do not generally keep good records of their history and tend to neglect their archives. This might make the historian’s job harder, but it also has the benefit that the history is not wrapped in the artifice of institutionalized memory.

Cédric Vincent is an anthropologist and postdoctoral fellow at Centre Anthropologie de l’écriture (EHESS-Paris), where he co-curates the Archive of Pan-African Festivals program supported by the Fondation de France.

More Editorial