Human Zoo

Still image from the 1969 BBC television series Civilisation

Colonial Method

Throughout colonial history, occidental forces seeking to capitalize on natural and human resources in their respective colonies employed the dehumanization of natives as a strategy to justify and maintain subjection on a massive scale. It was a project designed to equate the west with “civilization” and the rest with savagery, barbarism and the primitive mind. Abroad, not content with the domination and emasculation of peoples by force, coercive methods of western colonial practice advanced beyond the bloodied battlefield into the fertile grounds of foreign minds. The trick was to convince the native of his or her inherent inferiority. Utilizing science, religion and technology, colonizers sought to demonstrate to the native their moral, intellectual, natural and spiritual superiority.

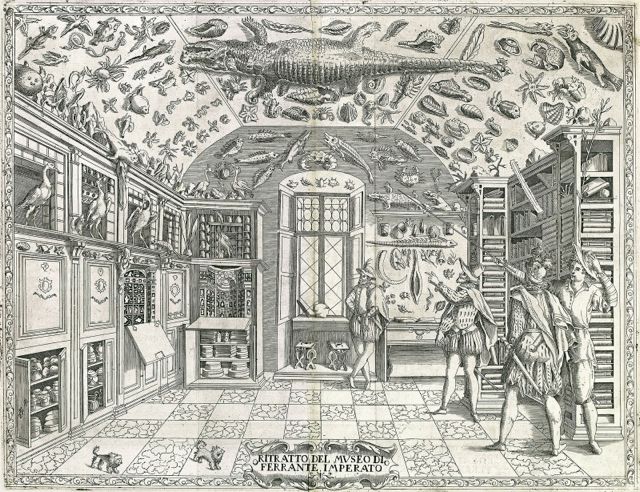

In the West, the domestic project of colonial dehumanization progressed along semiotic lines. Using fantastic tales of foreign islands inhabited by wild men and monsters, brought to western shores by New World explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo and Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, pre-modern white European society began to construct a positive image of itself measured against the abnormal creatures that inhabited strange lands elsewhere. The burgeoning Western desire to categorize, taxonomize and map the world and all its contents found form during the European Renaissance in cabinets of curiosities (the word “cabinet” here refers to its old definition of a small private room). These were collections of strange or unusual objects gathered together in private homes for the perusal of educated and refined minds (for which read the wealthy). According to anthropologist Gilles Boëtsch, “alongside ‘classical zoology,’ cabinets of curiosities also sought to contain fragments of creatures from the world of legend […] not forgetting the many imaginary bodies thought to belong to this or that monster celebrated in literature or folk tales.”1

A cabinet of curiosities engraving from Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples, 1599)

The apogee of this impulse to categorize arrived with the European enlightenment. By the 18th and 19th centuries, cabinets of curiosities had formed the basis of collections in both natural history and art museums, activity that ran parallel to and supported the unification of science, mythology and folklore in eugenics, phrenology, philosophy, history, medicine and literature. In reference to this era, Pascal Blanchard has argued that “over a period of five centuries one can observe the spread of an iconographic grammar, a corpus of imagery of the Other which manufactured and permanently defined the Other.”2 What is certain is that by this time European subjects moving through the streets of their respective cities, sitting at home, or engaged in some socio-cultural activity, would, by virtue of various media, have regarded their humanity as an incontrovertible fact, knowing that across the seas were beings closer to beasts than they.

One of the more bizarre methods for defining the Other, symbolically reinforcing the superiority of Caucasians and casting colonization as a noble humanitarian project, were what have become latterly known as human zoos: temporary public displays of natives imported from colonies who were both paid and made to live and work within fabricated environments or towns designed to faithfully represent their indigenous habitats.

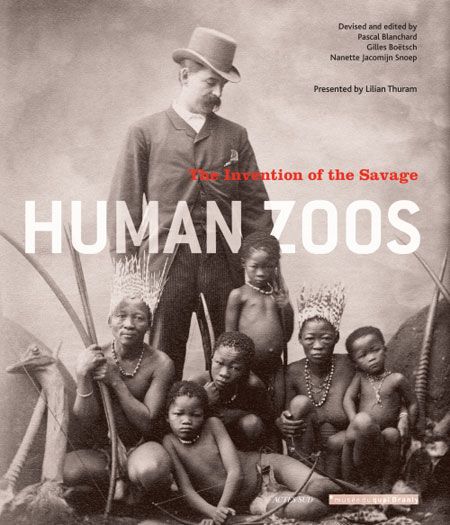

Exhibition catalogue for “Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage,” Quai Branly 2011

Critical attention focused on the disturbing practice of human zoos has been slow to emerge. However in 2011 an ambitious large-scale exhibition compiled disparate academic research in a single impressive and comprehensive display, bringing the little-known enterprise to public attention. Exploring the historical rise and fall of natives on display, “Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage” was staged at the Quai Branly museum in Paris, curated by Caribbean-born former international soccer-player Lilian Thuram, historian Pascal Blanchard and anthropologist Nanette Jacomijn Snoep. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue pitched the emergence and maintenance of human zoos, rising in the 19th century and disappearing by the mid-twentieth, as an effect produced by colonizing nations’ imperial will to dominate. As such the most zealous adoptees were countries with colonial interests including Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium and Japan.

Franco-British exhibition of 1908, aerial view

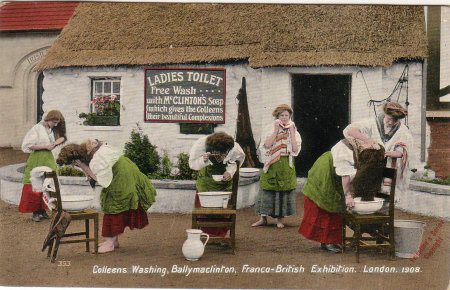

But human zoos were not stand-alone attractions. They featured as constituent parts of much larger national exhibitions, fairs and expos. These projects were vast ventures like the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London’s Crystal Palace, primarily showcasing sterling achievements in science, invention and industry. For example, the Franco-British exhibition of 1908, held in London’s White City had three native displays: an Indian village, a Senegalese village and a mythical Irish village named Ballymaclinton. Sponsored by McClinton’s Soap, it was described in the exhibition catalogue as featuring “genuine colleens at work at lace, embroidery, carpets and the various industries that have been introduced into the homes of the peasantry,” continuing, “whatever interest one has in the emerald isle […] Ballymaclinton cannot fail to interest and amuse.”3

Ballymaclinton colleens “fortune telling”

Ballymaclinton colleens “washing”

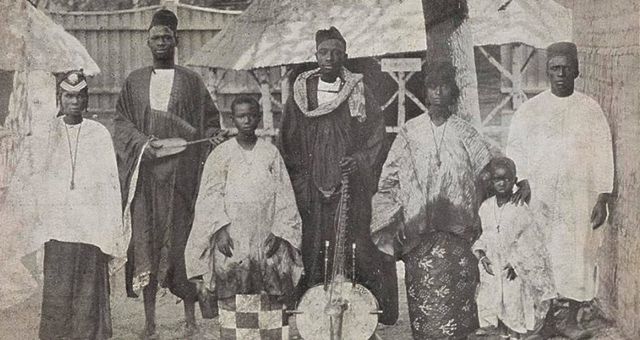

The purpose of these human zoos was to promote and reinforce (nationally and internationally) the superior status, wealth, refinement, power and intellectual achievements of the host nation. Naturally great exhibitions and world fairs were attractive propositions for smaller countries: those without colonial interests or the military might to put imperial aspirations into action, but who were nevertheless eager to make their mark on the world. Unfortunately, staging an authentic exhibition of this scale meant adhering to conventions of the format. Alongside wonders of science, art and industry came the display of human beings. And so in 1914 when Norway, a country without significant colonial interests, staged its own great expo to mark the jubilee of its constitution, the organizers included a human zoo featuring 80 Congolese natives.

Congolese village inhabitants during Norway’s 1914 Jubilee exhibition

Participatory Art

When Norwegian-based artists Mohamed Ali Fadlabi (born in Sudan) and Lars Cuzner (born in Sweden) discovered these past events, they were disturbed by their conspicuous absence from the promotional material and plans to revisit, restage and celebrate the 1914 fair. The duo felt this was selective amnesia and that Norway was showing a general unwillingness to confront a racist past that has informed an institutionally racist present. “We are instigating a discussion we hope leads to new questions,” the pair state on the project website. “Europe is becoming increasingly xenophobic” and in order to combat this regressive trend they want to “confront a neglected aspect of [Norway’s] past that still contributes to our present.” In order to expose what they believe Norway is seeking to repress, Fadlabi and Cuzner have devised European Attraction Limited (EAL): a participatory art project, in which volunteers will act as “natives” in a restaged Congolese village in Frognerparken, Oslo. EAL opened on the 15th of May and will run for approximately four months, closing on 31 August 2014.

However, EAL arguably raises more humanitarian concerns and potential human rights abuses than the original ersatz Congolese village it has been set up to critique. Despite the fact that the pair raised close to £99,000 in funds supplied by Public Art Norway (according to UK newspaper The Guardian), project participants will be unpaid volunteers, working from 12:00–8:00 pm each day for free. They are also responsible for financing their own travel and accommodation. Ironically these are worse conditions of work than predominated in the high-colonial heyday of human zoos proper. Even in the 19th and early 20th centuries, significant numbers of villagers were under a contract (however suspect), were paid a fee (however nominal), and were provided with accommodation (however ramshackle). Though maltreatment and forced labor were strategies that some employed, it is important not to fall into the trap of denying all those who were exhibited any agency – including Irish colleens as well as Congolese, Korean, Philippine and other “natives” – and forgetting that what they were engaged in was work.

Faced with worse working conditions than those existing two centuries ago, who would want to volunteer for EAL? Is it reasonable to assume that those attracted by such a proposition may not be of entirely sound minds? Furthermore, what type of person will be drawn to strolling through the village? How will they react to seeing human beings displayed as savage, subhuman exhibits of curiosity? What speaks volumes about Fadlabi and Cuzner’s seeming disregard for their volunteers, the perverse behavioral dynamics this project will produce, and the potentially traumatic, dangerous and abusive situations people will be putting themselves into, is the complete lack of provision for psychological assessment and care (carried out by qualified professionals) before, during and after the event. These oversights are compounded by the fact there will be no onsite security to protect the participants from members of the public or indeed themselves.

Aside from the contentious issues of free labor in participatory art and the potential physical and psychological hazards for volunteers in EAL, Fadlabi and Cuzner’s project also stands on shaky ground because of the contradictory nature of the whole undertaking. So far the duo have done a great job of raising awareness of the 1914 fair and drawing attention to the tired myth of Scandinavian liberalism and universal racial tolerance. But why not leave it there? Once the project is operational it is my belief that the bizarre nature of a village of “savages” will entirely smother any hint of criticality. In addition, don’t the very facts that Norwegian public funds are financing the project and that the city council in Oslo has granted the duo permission to build onsite at Frognersparken give the lie to Fadlabi and Cuzner’s assertion that the country is unwilling to engage with problematic aspects of its past and present? Instead of their desire to encourage real socio-political change through considered debate, EAL will instead pander to the same desire for the sensational, the monstrous and the exotic that began with cabinets of curiosities and ended up with “natives” in “natural habitats” at great exhibitions. In other words, the duo is reproducing what initially disturbed them the most. They are recreating the conditions and setting the stage for spectacular racism on a scale unprecedented in the country since 1914.

Still, all of this is speculation. It is entirely possible that EAL will be a landmark participatory art project that not only inspires policy change in Norway, but leads to profound epiphanic experiences for both participants and attendees. It is possible, but highly unlikely.

1. Boëtsch, G. (2011) ‘From Cabinets of Curiosities to the Passion for the “savage”’ in Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage, Paris: Musée du quai Branly

2. Blanchard, P. (2011) ‘Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage’ in Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage, Paris: Musée du quai Branly

3. Popular Guide to the Franco-British Exhibition (1908) Derby; London: Bemrose & Sons

Morgan Quaintance is a writer, broadcaster and curator. He is the producer of Studio Visit, a weekly radio show broadcast on London’s Resonance 104.4FM, featuring international artists as guests. As a presenter he works with the BBC’s flagship arts programme, the Culture Show.

More Editorial