Olamiju Fajemisin speaks to Shannon Tamara Lewis about her painted assemblages of limbs that evoke transformation as well as certain burdens.

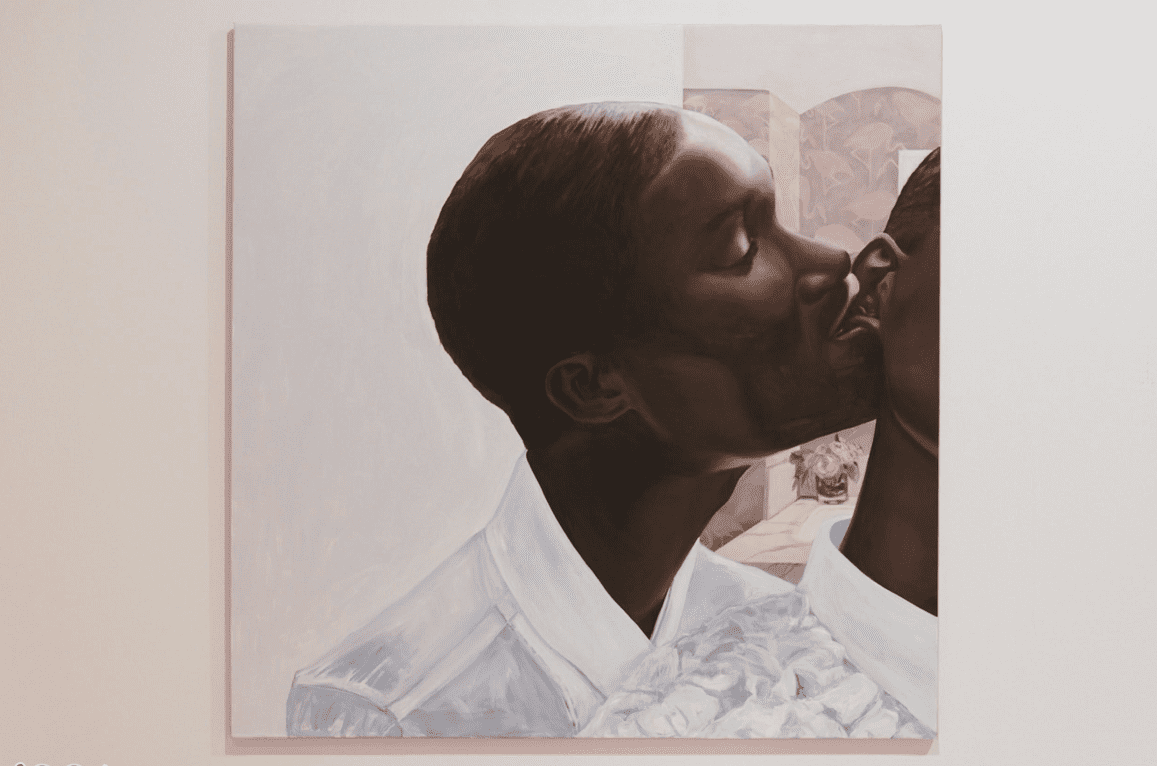

Shannon Tamara Lewis, Too Fast Ones: We Stole These Heads I, 2019. Oil on Linen, 2m x 2m. Photo: Guillaume Baeriswyl, Konkord Photography. Courtesy of Les Urbaines Festival

A new generation of young painters in Europe are using internet languages to create multilayered aesthetics and narratives. Revising traditional techniques with digital sensibilities, these artists are opening themselves and the medium up to possibilities that were previously unconsidered. In this series, Digital Strokes, we highlight some of these artists.

Shannon Tamara Lewis paints people in rooms. Dark-skinned people, unaware they are the subject of our contemplation, innocuously positioned, docile. Look longer and you may wonder who they are, or where they are and why. And so the layers of Lewis’s paintings reveal themselves. The artist, who studied at Toronto’s Ontario College of Art and Design before going to London to undertake an MFA at Goldsmiths, moved to Berlin four years ago. “Back then, making work about decoloniality and immigration,” she tells me over a video call, “I really had to defend my practice.” Instead of realigning her intentions, Lewis pivoted toward subtext.

Shannon Tamara Lewis, Everything and Nothing Is For You, 2018.

Oil on Canvas, 40 x 50 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Lewis’s paintings are quiet studies of fragmentation. Limbs, heads, faces, and furniture are conscientiously arranged, forming sites of living memory. “It’s about scattered identities, identities that are shifting and moving and can never be put back together as they were originally intended.” Let it be noted that Lewis considers herself a collage artist as well as a painter, in terms of both papier colleé and the reassembly of ideas. “I’m constantly collecting images,” she tells me, “collecting scenes, or hands, or spaces, then I put them together, literally, then start painting. I hold onto the images until I find the right space for them.”

Lewis’s attitude toward the staging of identities – to the graphic unity of ideas – recalls the practice of African American artist, author, and songwriter Romare Bearden (1911–88), whose much-loved artworks comprise a deliberate reassembly of fragmented images of Black life as he understood it. Collages included in his seminal Prevalence of Ritual series (1971) served as a rejection of the expectation held by patrons of African American art (specifically the Harmon Foundation) that Black artists should only reproduce their image and culture in their work.[1]This expectation was a burden. Like Lewis, Bearden’s images are composites of non-linear history, of direct and indirect experience. “When I conjure these memories, they are of the present to me,” Bearden once said. “Because after all, the artist is a kind of enchanter in time.”[2]

Shannon Tamara Lewis, Sometimes But Not Very Often, 2016. Oil on Canvas, 60 x 60 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Lewis’s milky palettes and elegant limbs distract from what is painted between the lines. It is only once we look beyond the compositions and question the circumstances of the staged identities before us that more can be revealed. There is an implicit urgency in Sometimes But Not Very Often (2016), for example. Two, maybe three half-bodies float in the foreground, moving, it seems, to nowhere. Brown arms intimately interlink, a shoulder and elbow jut forward, two hands gently grasp at each other. If the face had eyes it would look directly at us, but instead it disappears above the nostrils. The brown knot of arms look as if they could be peeled from the canvas like a piece of collaged paper. The figure casts no shadow. “A lot of my work is about bodies in different places and migration,” the artist says. “I take fragments from different places and put them together and layer them.” Lewis’s painted assemblages of “shapeshifting” limbs demonstrate perfectly the “joyful possibilities of transformation and the harried burdens of constant adaptation.”[3] She pairs aspirational fantasies with visions of gnomic, monolithic figures, reckoning the digital and social media-borne phenomenon of staging identities and artificial mobility with exhaustion – the multiple hands on her canvas are those of the “filmmaker and the performer, that of the painter and the shapeshifting subject.”[4]

In Fixture of Fantasy (2019), a woman’s black skin is again limned amid taupes and creams. Above her delicately painted lips, her body simply ends. Ruminating on the union of the words “fixture” and “fantasy,” the lines of a paned window appear more like the bars of a cell. “I collect images in architectural magazines, or Vogue. I look for pristine spaces that are quite beautiful but also quite staged and not really lived-in.” Recalling her own family’s experience with economic migration, Lewis paints this woman as trapped by the fantasy of aspiration: “There’s this idea you’re always supposed to be moving upwards, but what do the things we collect on the way mean? What does it mean to have a beautiful home?”

Lewis’s is a game of denial. Look at her paintings and no one will look back at you. “I like the idea of refusal and reveal,” she says. “I wanted to play with power, deciding what I want to reveal, and when.” Whereas the people in Sometimes But Not Very Often and Fixture of Fantasy are proportional, and exist in somewhat tangible settings, the subjects of her 2019 diptych Too Fast Ones: We Stole These Heads float on a more unusual plane. Measuring two by two meters, the life-size paintings were created last year for Les Urbaines, an interdisciplinary contemporary art festival in Lausanne, the latest edition of which was curated by Deborah Joyce Holman. This diptych, and another painting, The Warmth of Other Suns (2019), occupied a large, airy room in Espace Arlaud over the course of a long weekend last December. For Lewis, the commission granted a long-awaited opportunity to scale up. “I was reading a lot last summer, some Frederick Douglass, Saidiya Hartman and the ‘errant path’,” she says. “If I say my body can go anywhere, if it’s already a fugitive, then let me play with where I go.”

The heads in Too Fast Ones are smartly dressed – they lean against a wash of blush pink with white high-collared shirts. The figure on the left bites at her companion’s ear, across the gap between the canvases, and they both ignore us with closed eyes – they depart swiftly from the smaller-scale tangles of limbs and half-faces. Lewis’s ample invocations of the fugitive point to the multiplicity of self, the many possibilities for identity formation, and the potential for performance in post-internet painting. Her collaged ideas and body parts can be studied in many ways. Through Lewis’s contemplative practice, viewers can ask open-ended questions about their Black experience, as it pertains to them personally.

[1] Carroll Greene, Jr., Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual (Museum of Modern Art, 1971).

[2] Neda Ulaby, The Art of Romare Bearden: Collages Fuse Essence of Old Harlem, American South (NPR, September 2003).

[3] Alex Pittman, “Introduction: Can the Subaltern Fabulate?”, Shady Convivialities: On Tavia Nyong’o’s Afro Fabulations, Social Text Online, January 2020.

[4] Ibid.

More Editorial