La critique d'art et commissaire d'exposition Suzana Sousa nous livre un aperçu exclusif.

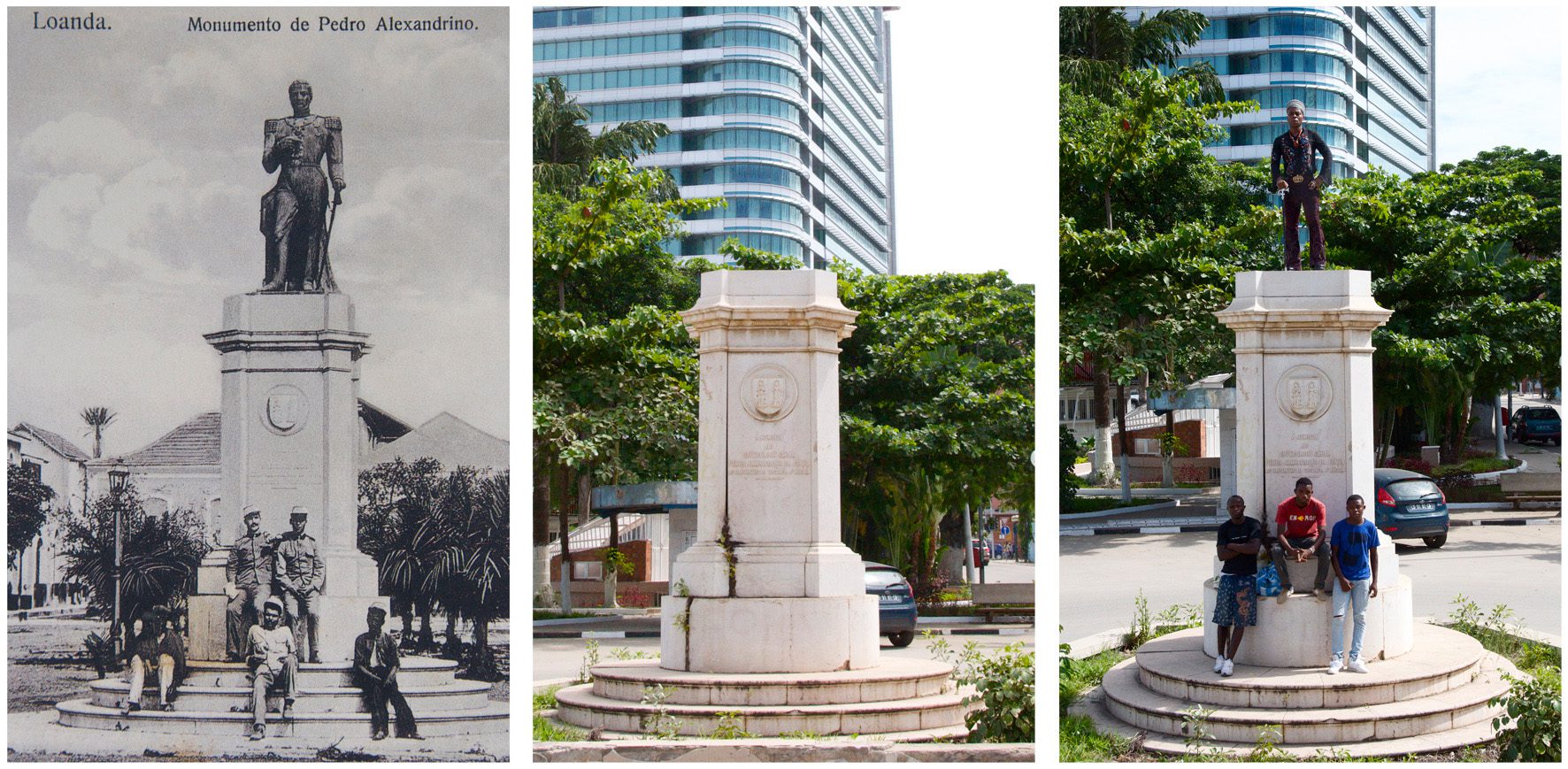

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Redefining The Power III, from ‘Series 75 with Miguel Prince’, 2011, triptych, photographic print mounted on aluminium, each: 120 × 80. © Kiluanji Kia Henda

Ces dix dernières années, la Triennale de Luanda – l’événement international le plus important de la capitale angolaise en matière d’art – a marqué la scène artistique de Luanda. Conçue par Fernando Alvim, cette manifestation a connu sa première édition en 2007, plusieurs événements plus petits y ayant préludé au cours des cinq années la précédant afin de préparer cette impulsion et fédérer des soutiens pour la Triennale. Ces années se sont caractérisées par la révélation d’artistes angolais sur la scène artistique internationale au moyen de conférences et de résidences d’artistes – de Miquel Barceló et DJ Spooky parmi d’autres. Au même moment, le projet était présenté sur la scène internationale, créant un espace dédié pour que l’Angola prenne part au débat sur l’art africain, non seulement à travers des artistes individuels, mais aussi via un positionnement national, même si Fernando Alvim était et reste un particulier à la tête d’une institution privée. Tel était le contexte dans lequel des artistes comme Kiluanji Kia Henda et Yonamine firent leur entrée sur la scène internationale et le contexte qui maximisa la fédération d’efforts déjà existants.

Dans un scénario duquel les musées d’art ou les galeries étaient absents, les collectionneurs privés et institutionnels constituaient les principaux mécènes en Angola. Toutefois, l’internationalisation de l’art angolais conféra de nouvelles responsabilités à ce groupe qui continua à soutenir les arts mais développa en parallèle une vision plus critique liée à leur exposition accrue.

L’histoire individuelle de l’art angolais a pris récemment un virage intéressant, avec l’attention du gouvernement et sa présumée – tout au moins l’espère-t-on – nouvelle politique qui sera mise en œuvre dans ce domaine, son champ s’étendant des droits d’auteur aux écoles d’art. En 2012, Kiluanji Kia Henda a reçu le prix national pour la Culture par le ministère de la Culture, pour l’internationalisation de l’art angolais. Encore plus récemment, le pavillon de l’Angola a gagné le Lion d’or de la Biennale de Venise de la Meilleure participation nationale à l’exposition « Luanda: Encyclopaedic City » de l’artiste Edson Chagas, une exposition organisée par Beyond Entropy (Paula Nascimento et Stefano Pansera).

Le pavillon commandé par le ministre de la Culture angolais a monté deux expositions qui, je pense, reflètent les changements qui s’opèrent dans l’art contemporain en Angola. L’éthique nationale que suggère le titre « Angola em Movimento » de l’exposition organisée par le commissaire Jorge Gumbe fait l’objet d’un questionnement par la pratique contemporaine et la façon dont les artistes se voient et se représentent eux-mêmes. Il existe une nouvelle génération d’artistes expérimentant avec différents médias, indépendants des idéologies politiques de l’histoire angolaise récente, des artistes qui se voient plutôt comme faisant partie d’une entité géographique globale, tant sur le plan politique qu’artistique.

De nouveaux projets et acteurs surgissent et déterminent l’actualité de la scène artistique de Luanda. Depuis 2012, Carlos Major a développé un projet curatorial, Vidrul Fotografia, qui consiste à présenter quatre artistes pendant une durée d’un mois. La dernière édition a exposé les œuvres de Kiwla, N’Dilo Mutima, Renato Fialho et Adiddy Love. Ce projet a le mérite de mettre de nouveaux artistes sur le devant de la scène tout en expérimentant de nouveaux lieux urbains, mais pas nécessairement des lieux d’exposition conventionnels. Ceci a été le cas lors de la dernière édition qui a eu lieu au bureau de poste principal de Luanda. Il en va de même pour e.studio, une entreprise culturelle initiée par António Ole, RitaGT, Francisco Vidal et Nelo Teixeira, un groupe d’artistes qui a développé un espace artistique visant à présenter et promouvoir la production et le débat sur les arts. Des institutions comme le Centre culturel portugais et la Fondation pour les arts et la culture, une organisation israélienne, sont également des espaces développant des programmes culturels réguliers avec des artistes nationaux et des curateurs.

Lors d’une discussion récente avec la photographe Indira Mateta, nous nous posions la question de la visibilité des artistes femmes angolaises. L’insuffisance du niveau d’étude est très probablement l’une des raisons de la marginalisation des artistes femmes, autant que les systèmes d’apprentissage informels qui tendent à les reléguer dans un rôle secondaire, contribuant à associer les femmes aux métiers de l’artisanat. Marcela Costa a essayé de mettre à mal cet état de fait pendant des années dans son atelier/espace d’art en rassemblant une communauté d’amateurs d’art et célébrant les artistes femmes. Toutefois, les artistes femmes ont toujours beaucoup de mal à être reconnues comme artistes contemporaines sur la scène locale.

Le monde de l’art à Luanda est jeune et plein de vie, fort d’un impact politique qui reste à être compris. Avec des subcultures comme le kuduro, il représente une nouvelle forme de politique qui implique la vie de tous les jours et se reflète dans une action quotidienne. Dans un pays qui a toujours passé sous silence les problématiques telles que la politique, nous assistons ici à une évolution passionnante.

Suzana Sousa vit et travaille à Luanda comme commissaire d’exposition indépendante. Elle est une des commissaires de la prochaine Triennale de Luanda.

Traduit de l’anglais par Myriam Ochoa-Suel

More Editorial