Tasked with revising the collection of the Nationalgalerie with a non-Western focus, the exhibition Hello World at Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin recontextualizes artworks, revealing hidden narratives and demystifying the role of the museum.

Exhibition view Hello World. Revision einer Sammlung / Colomental Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, 2018 © Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Thomas Bruns

Despite records and memory, looking at the past is never a straightforward task. The more we know about the world, the more our perception of history changes, and so looking back can have an immediate effect on tomorrow. This summer, Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art opened its major exhibition aimed at revisiting the collection of Nationalgalerie of the five Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (including Alte Nationalgalerie, Neue Nationalgalerie, Museum Berggruen, Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg and Hamburger Bahnhof), which has had predominantly a Western focus. There are also works on loan to help contextualize the collection, though it’s hard at times to ascertain which ones those are and

their origin.

Entitled Hello World – Revising a Collection, the exhibition takes as a point of departure artworks from the collection that engage with non-Western topics and puts them into a historical and socio-political context. Split into 13 different narratives and featuring more than 250 artists, the exhibition gives each chapter its own discourse, linking the time when the artworks were acquired (mostly in the 19th and 20th centuries) to today. Although the different sections have different curators, each exhibition chapter is focused on moments of transcultural exchange and artistic collaboration and the consequent cross-pollination.

One great realization from trawling the collection, however, is that there are no artworks that relate directly to Africa, which proved to be an eye opener as well as a challenge for the curators. Nonetheless, given that all the chapters have common threads, there’s plenty in the exhibition that relates to Africa and the African experience in indirect yet relevant ways.

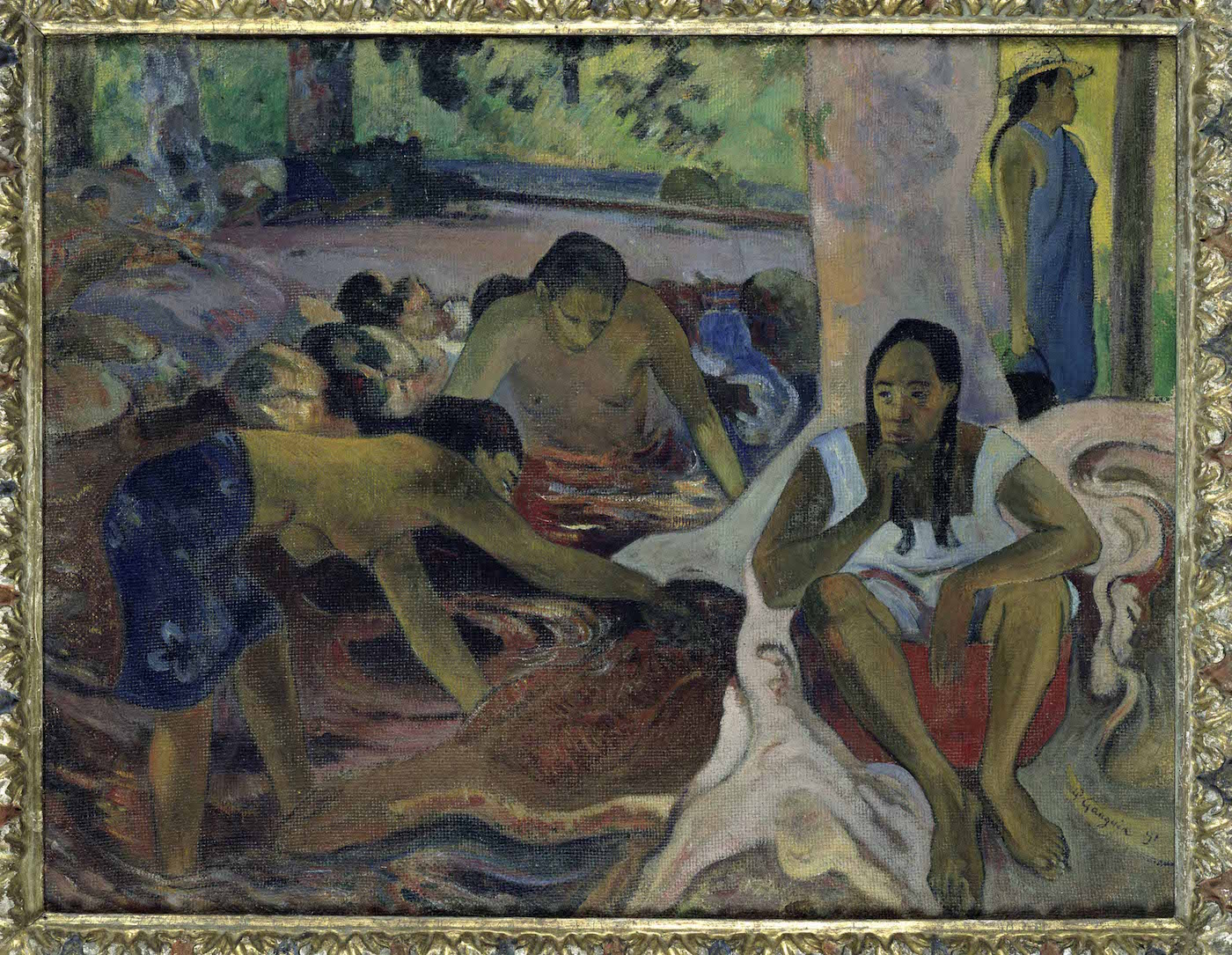

Paul Gauguin, Tahitianische Fischerinnen, 1891. Oil on canvas, 71 x90 cm © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Loan from the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung / bpk / Jörg P. Anders

Take for instance the chapter Making Paradise Places of Longing, from Paul Gauguin to Tita Salina. While focusing more on South East Asia, the show curated by Anna-Catharina Gebbers reveals timely issues surrounding cultural appropriation and market expectations of non-Western art and artists. Featuring several orientalist works by artists such as France’s Horace Vernet, one of the points the exhibition makes is how orientalist motifs were often made up by European artists. For example, artists like Gauguin didn’t necessarily paint real scenes or even people but instead often drew their subjects from ancient temple sculptures and sensualized street scenes, as seen in Horace Vernet’s Slave Market (1836) which looks like the depiction of an imagined harem.

With regard to the artistic technique these works have their validity; however, the approach also raises important issues concerning the adequate representation of othered groups. Moreover, this highlights the role of art in colonialism and today’s role of the museum in exposing that. Cultural appropriation and its dubious representation is an age-old practice, yet only recently has it been put to question in the arts, whereby (often Western white) artists are given accountability for their actions. Yet, this exhibition complicates that same notion by telling the story of Javan artist Raden Saleh.

Considered to be Indonesia’s first “modern” painter, Saleh had a multifaceted career in which he reinvented his identity and art to fit with the industry expectations of orientalism. By definition, Orientalism is a term used by art historians, literary and cultural studies scholars for the imitation or depiction of aspects in Middle Eastern, South Asian, and East Asian cultures. On show are self-portraits of Saleh that document his evolution from European dandy to Arab looking, hence playing with his ethnic ambiguity to capitalize on the then market demand for “Middle Eastern” art. Naturally, parallels can be drawn to today’s interest in art by African artists that appears to be “African” and deals with hackneyed “African” topics such as identity, poverty or trauma.

Walter Spies, Rehjagd (Deerhunt), 1932

oil on canvas, 60 × 50 cm © 2012 Adrian Vickers. Reprinted from „Balinese Art“ by Adrian Vickers. Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd

Cultural appropriation and influence may be similar but are very different things. This chapter also features how artist Walter Spies straddled both. The German painter moved from Dresden to Bali, Indonesia, in the 1920s where he co-founded the artist group Pita Maha together with Balinese stone sculptor and architect I Gusti Nyoman Lempad. This part of the show also complicates how we look at art history by charting the artistic evolution of Spies whereby his style becomes visibly more influenced by Indonesian art than the other way around. Another less known fact that is highlighted here is that despite having European members, the art collective Pita Maha had the aim to disconnect from the West and create a new art genre. However, the fact that Bali had started to become a top tourist destination probably played a role in their motivations.

The reasons for the suppression of these types of transcultural exchanges in art history may be the same as for the lack of artworks related to Africa in the collection. For centuries the West has deliberately contrived the image that it is the best, and omitting its sinister stories is a way of erasing them from collective memory and keeping a pristine profile. Colomental – The Violence of Intimate Histories is the chapter in Hello World that deals with this issue head on, though it begs the question as to why no Black German curators nor artists were involved. Curated by Sven Beckstette and Azu Nwagbogu, nonetheless, it features a work by Dierk Schmidt which aptly complicates our perception of history and opens up new possibilities for life and art.

The Division of the Earth – Tableaux on the Legal Synopses of the Berlin Africa Conference

(2007) is a series of paintings that illustrate two main ideas from the Berlin Conference of 1884–85. One of the paintings reflects on the accuracy of the language used then by listing the names of the African territories with their pre-colonial names such as Kingdom of Benin. This agency is furthered by showing a letter by an African nation to the European participants of the conference informing them that African nations should have taken part in it too. This not only confirms the agency of Africa but also reframes colonialism as an act of war. Yet the strongest element of the work is the Tableau 12 Plainte de la HPRC which makes visual the steps needed to grant reparations to former German colonies. For this, Schmidt collaborated with lawyers, historians, and activists from Namibia and Germany as well as at the Leuphana University of Lüneburg in Germany.

Schmidt’s project was also presented at the National Art Gallery in Windhoek, Namibia, and will hopefully travel the world. This multitude in perspectives and actions in Hello World is what gives the show its reason to exist. However, the show’s mammoth size also impedes visitors from engaging with the show’s most thought-provoking ideas. For instance, in the New York Times its writer prefered to highlight the less relevant point of the “lasting impact of the German painter Walter Spies on contemporary Balinese art” rather than the exchange or the influence of Balinese art on German painters.

Offering new points of view is an ongoing task, and instead of ending the narrative it creates yet more perspectives. May this monumental exhibition be the first big step in reframing established art history narratives.

Hello World – Revising a Collection is on show at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, until 26 August 2018.

Review by Will Furtado.

More Editorial