The continent's leading photography festival is a rallying cry for African self-reliance and a platform for new voices, writes Obidike Okafor.

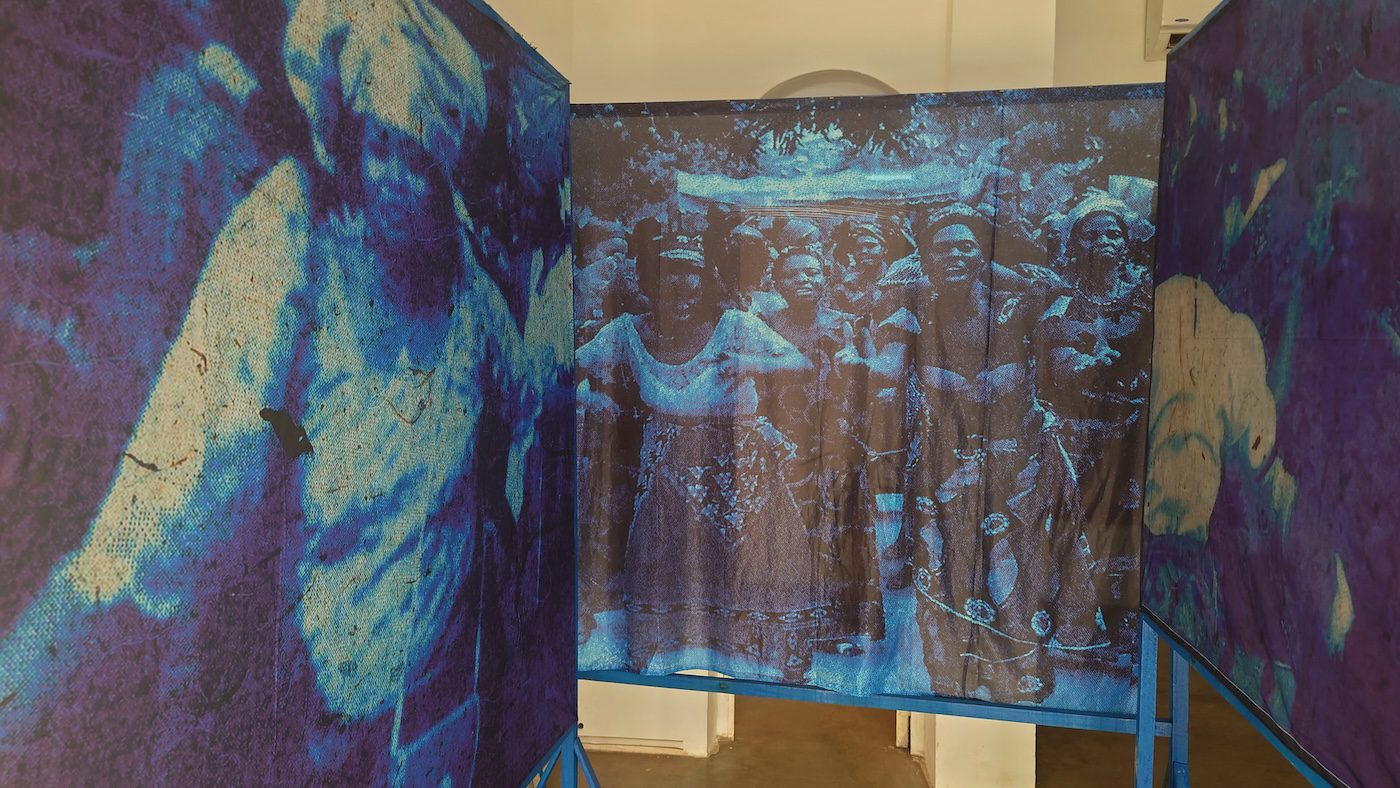

Myles Igwe, Ndi Nwanyi , 2024. Installation view at 14th Recontres de Bamako. Courtesy of the Bamako Biennale.

Celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this year, Mali’s Rencontres de Bamako is a testament to resilience. Recently Africa’s premier photography biennial has navigated formidable challenges just to keep going. Yet in exploring how verbal and non-verbal communication manifests through imagery, gestures, and shared memory, the fourteenth edition engages viewers in thoughtful conversations about identity, history, and the future.

In a context in which conflict and displacement have disrupted countless lives, the biennial demonstrates not only its organizers’ and the artists’ determination but also art’s ability to endure, inspire, and connect. Rencontres de Bamako has historically been run by the government and the Institut Français, so the absence of French support and significant budget cuts this year could have diminished the event’s significance. Instead it has become a rallying cry for African self-reliance which retaining its role as a platform for new voices.

The theme is KUMA, meaning “speech” or “voice” in Bambara, and a central question it considers is “Faced with the challenge of Artificial Intelligence, what will become of African Intelligence?” As technology blurs the boundaries between real and virtual, the exhibition, titled La Panafricaine, probes the role of photography in preserving authenticity, heritage, and human emotion. I found the result to create thoughtful conversations around what perspectives photographers can adopt in a world where the very nature of images is being redefined.

Maheder Haileselassie Tadesse, Between yesterday and tomorrow, 2024. Installation view at 14th Rencontres de Bamako. Courtesy of the Bamako Biennale.

Thirty photographers were selected for La Panafricane. Ethiopian photographer Maheder Haileselassie Tadesse earned the jury’s top prize for her evocative exploration of time and memory, superimposing nineteenth-century archival imagery made by Europeans with her own photographs and family albums. Nigerian photographer Victor Adewale, whose work is largely documentary, and Ivory Coast’s multimedia artist Willow Evann also received accolades, while honorary mentions were awarded to Mali’s Seyba Keita and Senegalese-German artist Dior Thiamm, whose emotionally charged works resonate deeply with audiences.

Myles Igwe, Ndi Nwanyi , 2024. Installation view at 14th Rencontres de Bamako. Courtesy of the Bamako Biennale.

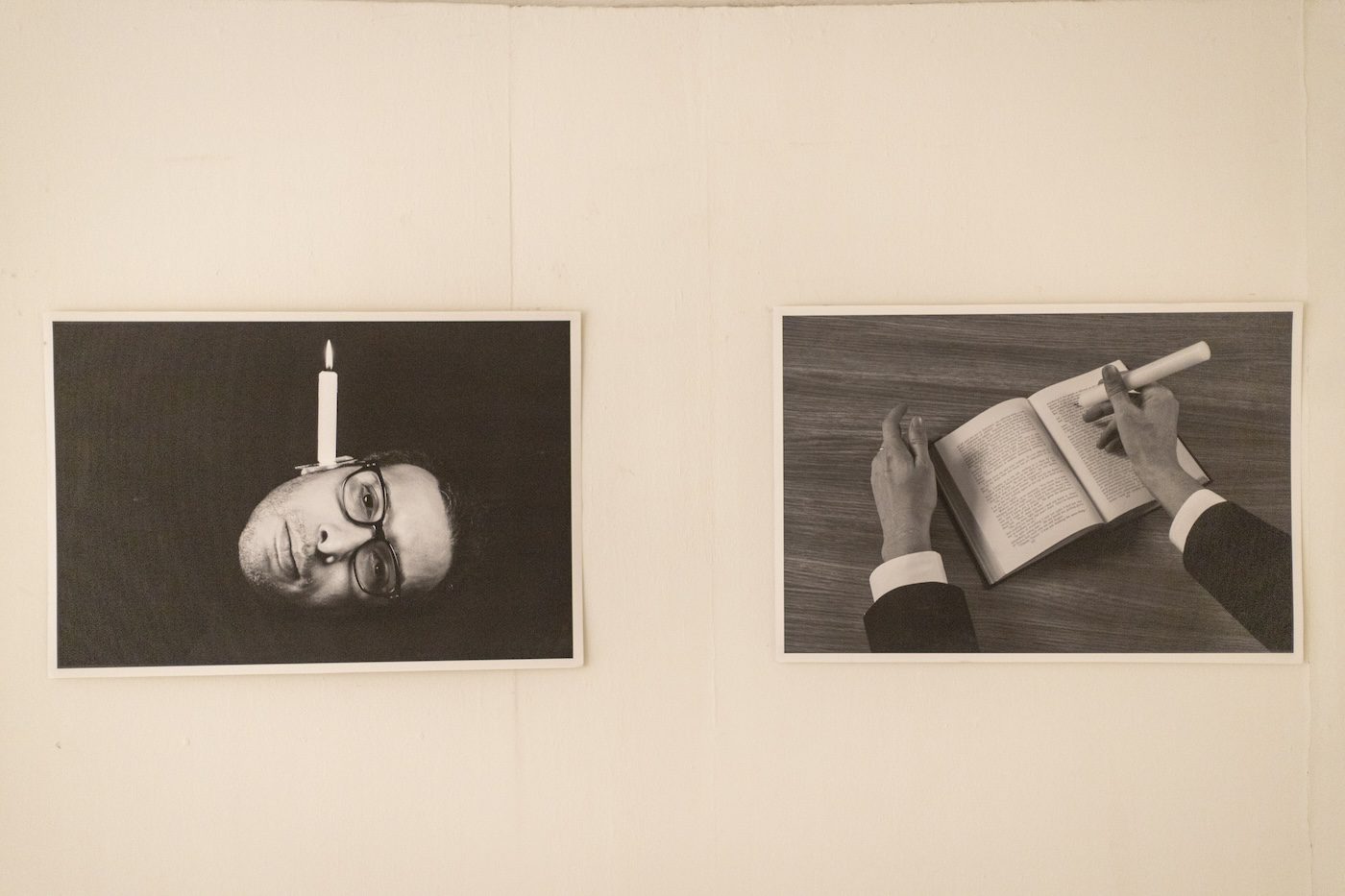

Nigerian artist Myles Igwe presented an installation titled Ndi Nwanyi, combining photography, virtual reality, and sound to explore Igbo funeral rites. “Photography can transcend boundaries, turning local traditions into universal conversations,” says Igwe. In their works, Zimbabwe’s Cynthia Matonhodze and Morocco’s Mounir Fatmi blended visual and verbal storytelling. Matonhodze’s A Place to Call Home juxtaposed archival photographs with the narrative of William Phiri, a retired migrant worker, creating a poignant exploration of aging and belonging. Fatmi’s Calligraphy of Fire used images of burning candles to delve into the tension between knowledge and censorship. These works demonstrated photography’s capacity to engage with viewers on multiple levels.

“We asked where is the African voice now in the world, in Africa and in the Diaspora,” explains Igo Diarra, the gallerist who is artistic director this year. “We talk for us. In the past the politician’s voice was very resonant, but nowadays we believe that the artist’s voice should be more strong, like that of musicians and writers. This is why we challenged the photographers to bring new conversations, to bring new voices.”

Mounir Fatmi, Calligraphy of Fire, 2024. Installation view at 14th Rencontres de Bamako. Courtesy of the Bamako Biennale.

Yet the artists felt the biennial’s logistical and financial difficulties. Moroccan photographer M’hammed Kilito lamented the decline in attendance by international art professionals. “These last two editions suffered from several issues – financial, logistics, and lack of savoir faire – and the biennale is not seeing the affluence of professionals it used to have,” he says. “For example, besides a few photographers this year who were able to attend, they were no art professionals who could help by writing about the biennale and help foster more visibility and maybe enable the participating photographers to see some interest from institutions and art curators.”

Diarra acknowledges the difficulties, pointing to a need for support from within Africa. “We have many wealthy people on this continent who could support the Bamako Biennale, but they don’t yet see the value of art. Africa must champion its own initiatives,” he said. Diarra praised the resilience and creativity of the artists and curators who brought the biennial to life despite working with a shoestring budget.

M’hammed Kilito, Before it is done, 2024. Installation view at 14th Rencontres de Bamako. Courtesy of the Bamako Biennale.

“Executing a biennial of this magnitude is very hard with a limited budget,” Diarra tells me. “So we had to be creative. I am grateful to all the selfless curators, artists, because they were very understanding and helped ensure that the biennale came out well. For them, the participation was paramount – it’s not the money, it’s not that, but it’s the idea. And I believe Africa should support a great African initiative like the Bamako Biennale.”

Since its inception, the Bamako Biennale has launched the careers of trailblazing photographers like Samuel Fosso, known for his iconic self-portraits that challenge stereotypes and reimagine history. This year’s biennial continued to serve as a platform for emerging talent while celebrating established voices. Diarra is right that the absence of strong backers this year should serve as a wake-up call, highlighting the need for art from Africa to be championed by its own communities and diasporas. Like any other art institution, the biennial’s future lies in its ability to secure sustainable support.

By John Moussa Kalapo. Installation view at 14th Rencontres de Bamako. Photo: Obidike Okafor.

Thus the 2024 Bamako Biennale is not just an event but a stark reminder of the challenges ahead. To maintain its status as Africa’s premier photography festival, it must secure long-term strategic partnerships. It is a call to action for African philanthropists, institutions, and governments to recognize the value of art and invest in its future. It carries with it a powerful message: art from Africa, like the continent itself, is resilient, dynamic, and boundless. It thrives not in isolation but through dialogue, innovation, and mutual support.

The 14th Bamako Encounters – The African Biennal of Photography will be held from November 16, 2024 to January 15, 2025 in Bamako, Mali.

Based in Lagos, Obidike Okafor is a content consultant, freelance art journalist, and documentary filmmaker.

ON PHOTOGRAPHY

More Editorial